This first post for the second book club is available to everyone, to let people see what they might be missing by not participating. The rest of the book club will be restricted to subscribers, and commenting privileges always are. The first book club was a ton of fun so please consider subscribing, reading along, and taking part in the conversation.

My story is not a pleasant one; it is neither sweet nor harmonious, as invented stories are; it has the taste of nonsense and chaos, of madness and dreams - like the lives of all men who stop deceiving themselves.

When I think of Herman Hesse, I think of the 20th century.

Much has been made of the modernist turn that preoccupied the last century; I have discussed it myself, in my ham-handed way, in this space. There are all sorts of conventional tales of a collapse of traditional meaning and the sense of apathy and directionlessness that accompanied it. There are also, as in all things, counter-narratives that reject these pat stories. But it’s fair to say that, as the world devolved into two massive wars, enabled by quantum leaps in science and technology, a critical mass of thinkers and writers and seekers began to search for a new kind of meaning, one that rejected what they saw as antiquated narratives of religion and ideology and substituted instead something transcendent and deep. Hesse was a consummate seeker, a writer who considered (and refused to ever stop considering) what it meant to be a human, particularly the kind of human who wanted to live authentically.

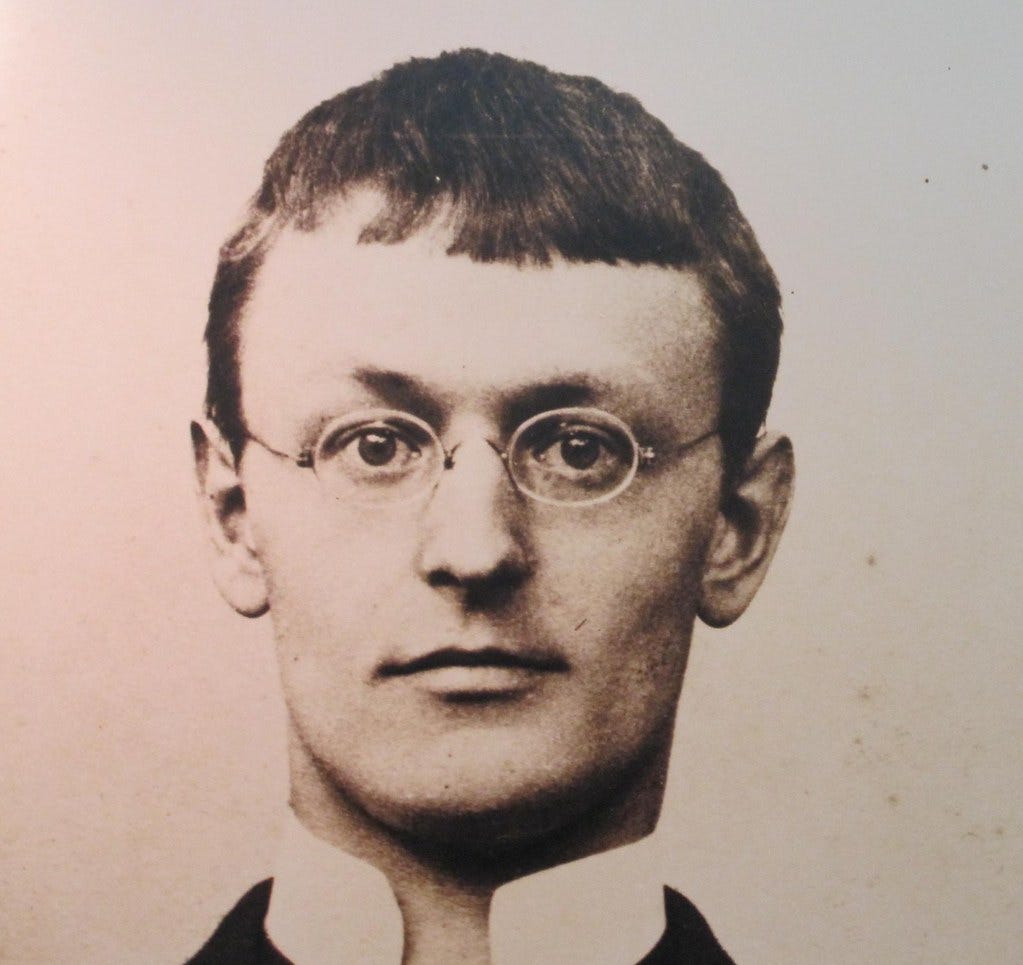

Hesse, the son of a fairly well-to-do German couple, was raised with an understanding of Indian philosophy and mysticism; his mother spent significant portions of her life in India and was conversant in Buddhism and Hinduism. Hesse’s family ran a successful printing company and he was fairly privileged in his youth, and he went on to fame and influence in Germany, winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1943. But still he did not live a happy life. He had several failed marriages, including to a schizophrenic woman, his son was chronically ill, and he suffered from lifelong depression. His last novel was published nearly 20 years before his death, and though I have not found that one source to confirm this, it always struck me that he was tortured late in life by his inability to complete another novel. He’s also suffered critically, pretty much since winning the Nobel. As Adam Kirsch pointed out in a fine New Yorker piece a few years ago, Hesse has always attracted a good deal of critical disdain, even beyond the status you’d expect of dead white German men in the current literary world. His fiction has long been associated with an adolescent tendency, chiefly because of his recurring themes of rootlessnesss and angst derived from a lack of meaning, which are common to teenagers - but then, those preoccupations are what make his work beguiling to the right kind of person at the right time.

He explored these themes, to one degree or another, in all of his published work. I have read four of his novels. Steppenwolf, nominated by many as his finest, tells the story of a conventional man who unexpectedly discovers a deeper, fuller, more visceral world that was hidden by the conventionality and reflex that once governed his every action. (He also discovers dancing. So much dancing.) It’s a good book, and its protagonist is an old fuddy duddy, which is unusual in the canon; reading it as an undergrad, I always imagined him as the ancient German prof who (in a heavy accent) taught the seminar in the humanities class where I was assigned the book. But while Steppenwolf is not long in comparison to many other novels, I find it wears out its welcome a bit and could have stood some pruning. Siddhartha, as the name implies, tells the tale of a Buddha (Hesse is canceled, in other words) and how he reaches for transcendent reality hidden by attachment and the pleasures of the world. I say a Buddha and not the Buddha, despite the fact that they share the same name, a quirk I find… annoying. It’s a very direct and unapologetic rumination on meaning and truth – too direct, I think, as Hesse’s fiction is always philosophical and taking it to the next level results in a book that feels to me like it should just drop its vestigial fictive natural and be a philosophical tract. The Glass Bead Game is beloved by many, and like seemingly all of his work depicts a man’s development into a new form of consciousness. I find the setup interesting, in its strange monastic order and the titular game, and I get why people fall in love with it. But its also meant as a parody of the kind of biographical work that Hesse had himself written for much of his career, and for me that parody never lands; it may be the impact of reading in translation, but I always feel there’s some level the text is working on that I don’t understand.

Demian, which I also read in college, is the one that snaps for me. It’s the story of (get this) a young man emerging into a higher form of consciousness, in this case our protagonist Emil Sinclair. The vehicle that transports him there is another young man, slightly older, named Max Demian. Demian rescues Sinclair from a beautifully drawn childhood scrape of the kind that seems like the end of the world at that age. Demian’s explicit origins seem ordinary enough, but there is something otherworldly about him, and he flits in and out of the novel just enough to seem truly unknowable. All of this is happening against the backdrop of gathering darkness and seemingly inevitable war. If I recall the novel correctly this is not explicitly what we now call World War I, but that war was raging as Hesse wrote the book; he had hoped to enlist but was declared medically ineligible due to his bad eyesight and an unsettled neurological condition. Over time Hesse would come to see that war as a symptom of the deepening madness of German nationalism, and Demian’s distaste for Prussian conventionality reflects this revulsion. Hesse would go on to passively resist the Nazi regime, aiding several who fled into exile and continuing to engage with the work of Jewish authors. His work would eventually be banned by the regime, but this has not prevented some for condemning him for failing to more forcefully fight Nazism.

I will warn you now: in common with all of Hesse’s work that I’ve read, Demian is a book that wears its philosophical heart on its sleeve. If you’re not a fan of novels that deal directly in philosophical concerns, with characters stopping to openly ponder the real nature of meaning, you are unlikely to enjoy this book. I thought it would prove a good contrast with The Cement Garden, which is a book that is felt and not thought and which is interested in decay rather than transcendence. You also have to be cool with an intent examination on the micro, rather than the sweep of the macro; the book is set against hugely momentous historical events, but its relentless focus is the intellectual and moral maturation of one generally unexceptional German man. But if you vibe with it, there are many treasures here. Hesse is an efficient and lean writer, the book running no more than eight chapters, and he has a way of cutting to the heart of matters. Sinclair’s searching never seems less than authentic to me, and I feel I know his wandering heart like I know mine. And there’s some knock out sentences here too. From the unnamed introductory text, which also includes the quote above:

I have been and still am a seeker, but I have ceased to question stars and books; I have begun to listen to the teachings my blood whispers to me.

And the very end of the book is an absolute knockout. Come, join us.

A little practical business - as several of you have pointed out, there are multiple available translations of this book available, and I didn’t designate one when I announced this book. That’s my bad; I’m still getting a handle on things here. I will be working out of the same Perennial Classics copy I bought at the Central Connecticut State University bookstore in (I think) 2002, which was translated by Michael Roloff and Michael Lebek. But I think people who got their hands on other translations should be fine to use those, and we can compare notes in the comments.

Please read the first chapter, “Two Realms,” and the second chapter, “Cain,” by Wednesday, November 3rd, when I will have the first chapter-by-chapter post up. Use the space below to comment as you would like. If you have read this book previously, you may comment on your overall experience or impressions, but please don’t share any plot details, to preserve the experience for others. And be good to each other.

Alright, alright. You have successfully hooked me with the book club. Subscribed.😉

I recently read The Glass Bead Game and loved it, so I'm excited for this. Bring on the sermons by mystical Germans! I might even comment on the discussions if I can think of anything intelligent to say (I didn't for The Cement Garden, though I enjoyed the book, if enjoy is the right word).