Chapter 18

Though the bartender had given no sign of predatory behavior the night before, Haojing felt a low-level paranoia that she had been directed out here to be trapped. The tributary was tucked away in a shaded corner of woods fairly far from the settlement, and even though she had taken her horse down to the river the night before to drink she was certain she would never have noticed this offshoot on her own. The woods were too thick to ride, and leading her horse through the brush by hand took so long she again contemplated letting him free. She could not stop herself from concluding that it was the perfect place for an ambush.

But the old concrete pipe that once must have pumped water into the tributary was right where he had said it would be, and that was at least a little reassuring. There was now a good 25-meter gap between the pipe and the water, another artifact of a changing landscape, and the pipe itself was bone dry. There on the side of the pipe was the Colony’s ant symbol, old and worn and barely visible, just like he had said. Still she eyed the whole area suspiciously, and paced around near the entrance for a full 20 minutes before she committed to walking in.

Again she had pangs of worry about her horse.

“What am I going to do with you?” she said, looking around her. She told herself that this was safer than anywhere, out in the middle of nowhere, without a hint of recent human activity. She walked him over the edge of the tributary and pulled a short length of rope out of her pack, then tied it to the reins and to a tree. Satisfied that he’d have a little more room to shuffle around, and to get water, she gave his mane a stroke.

“I hope I can come back for you,” she said. As she did, she noticed a structure covered in vegetation a bit upstream from where she stood. Picking her way through vines and bushes, she moved closer to it. She could see rusted metal hunkered over the tributary, covered in vines to the point of being unrecognizable. She reached over and grabbed one of the thick vines. It bit into her calloused hands, but she grasped it firmly and pulled. As the vine pulled loose, she made out the structure’s function: a waterwheel, fashioned out of carefully-machined but clearly salvaged parts. No more than a decade old, or so she figured. The vegetation clung to every inch of the thing, gumming up the moving parts, but as she cleared vines away the rusted gears began to betray a little give. She wrapped her hand in a bandana for protection from the rusted metal, then yanked on the wheel, which with her grunting and steady force finally turned a bit. As it did, the gears it was attached to budge a bit, though after 15 degrees or so of movement the apparatus came up against its rusted limits and refused to move. She followed the machine to its mechanical endpoint and noted where it ended in a lonely piston, disconnected from anything, rusted forever in place. She circled around the machinery, looking for anything useful, but came up empty. She knew it was time, and turned to face the pipe.

She clambered up onto the lip of the concrete, casting another glance at the surroundings, and saw no obvious danger. She pulled out her flashlight and made a silent prayer that its batteries would hold out. She brought the beam up to the ant symbol, checking to see if there was any additional detail she had missed in the dim ambient light of the riverside. But there was nothing. She swept the light around inside the pipe. Aside from lichen clinging to the sides, there was nothing to see up until the pipe bent some meters ahead of her.

She steeled herself and walked forward in the pipe. Her instincts told her that the flashlight betrayed her position, but she could not bring herself to move forward into the dark without it. Her footsteps echoed behind her; the air was stale and smelled vaguely of rust. She reached the bend in the pipe quickly, and unsurprisingly found it led to more pipe. Casting a long gaze back at the entrance, a perfectly round disc of light in the distance, she turned and headed deeper underground.

She moved cautiously through the narrow confines of the pipe, habitually checking behind her. She walked steadily for twenty minutes, trying to estimate how far she had gone, but found it impossible. For some time she hoped for a storm drain or other opening overhead, if only to see the light and feel some connection to the world above ground, but realized that with the pipe as dry as it was, this was impossible. After trudging for a while longer, she contemplated heading back, asking around more at the settlement, but just as she made up her mind, she came to a fork in the pipe, and with it another faded stencil on the wall, showing her the way to go.

She was not five minutes down that direction when she began to hear things from ahead of her – muffled movements, clatter, odd pulsing noises she could not make out from this far away. She flushed with excitement; whatever else lay in store for her, she was unlikely to find that she had come all this way for nothing. Still, she felt herself in a dilemma: was it better to move loudly, and give up her position and the chance to take in the situation before she acted? Or was it better to sneak in quietly and risk looking like a thief? Either way, there was nothing to do but go on ahead.

A little ways after she heard the noises, she saw a faint light spilling into the pipe. A hole had been crudely carved into the side, directly underneath some rusted metal machinery that was embedded in the roof of the pipe, like she had seen in a few other places along the way. She peeked her head out, extinguishing her flashlight as she did so. The hole opened out into some sort of maintenance room, an underground concrete den festooned with pipe fittings and release valves and other rusted plumbing. A set of steps led up to a higher level, a sturdy metal banister running alongside. The dim light poured in from a hallway above. The noise was clearer now; she was sure she heard voices, the clatter and banging of maintenance, and the hum of electronic power. She steeled herself and rounded the corner.

She found herself in an entranceway, of sorts. What had likely been a set of storage rooms had been turned into a checkpoint, or a guard station. A long desk had been fashioned from scrap and stood separating her from an impressive steel door that hung open behind it. A gate between the desk and the wall was similarly ajar. Seated at the desk, a tired-looking gentleman with salt and pepper hair was tapping at an ancient computer. Not knowing what else to do, she walked out into the open and stood in front of him. Absorbed in his task, he just kept pecking away for several agonizing seconds.

“Um,” said Haojing, standing in the middle of the entranceway, hands empty and at her sides, ponytail hanging limply against her face.

He sat up with genuine shock, rocking back on his chair with such violence that she thought he might flip completely over. He fumbled in a drawer in the desk, pulling out a revolver, which he waved around in her direction. She threw her hands up quickly in front of her. She took a short step behind her, contemplating whether to bolt out back; with the pistol bobbing around in his hand, she figured she had a decent chance. But to run now would certainly make her look guilty.

“Hold on, just hold on,” she said, hands in the air, trying to sound soothing.

“Carl!” he shouted behind him. “Carl, get in here!”

She kept her hands raised and stood stock-still. The longer she looked at him, the less threatening he seemed, and with functional ammunition now so rare, it was hardly ever clear just how dangerous any given gun happened to be. But that knowledge seemed academic with the barrel of the revolver still bobbing around a few feet in front of her. From down the hall she heard the clatter of footsteps. Another middle-aged man rounded the corner. He was dressed in a tattered white lab coat and looked disheveled. His eyes widened when he saw Haojing standing there, and wider again when he saw the gun in the other man’s hand.

“Jesus, Wei, put that thing down!” he shouted. Even in the commotion Haojing could not miss the oddly metallic, digital sound in his voice. She peered at him and saw it on his throat: the tell-tale surgical scars indicating that he had an artificial voice box, a cybernetic prosthesis.

“She snuck up on me,” said Wei, his voice shaking, still clutching the gun.

“Well, that’s your own fault, isn’t it,” said the other man, coming over and laying a reassuring hand on his friend’s arm. Wei glanced at him, finally taking his eyes off Haojing, and dropped the gun to his side, looking sheepish. “And snuck isn’t a word, you know.”

“Sorry. Ah – sorry,” said Wei to Haojing. “But who the hell are you? What are you doing here?”

Carl walked forward through the gate and extended a hand to Haojing.

“You’ll have to forgive my friend,” he said, grasping her hand in a firm embrace. “We don’t get a lot of visitors coming through this old entrance anymore.” He looked off in the distance for a moment, nodding to himself. “We don’t really get a lot of visitors, period.”

“Ah, it’s OK,” said Haojing. “I didn’t mean to startle you.”

“What exactly are you doing, crawling around in a sewer pipe?” said Wei, clearly still suspicious. Haojing contemplated her options, and went with the direct approach.

“I’m looking for the Colony.”

Wei and Carl looked at each other. Carl arched one eyebrow and glanced back at her.

“Well then I have good news, young lady. You have found them.”

Chapter 19

Without ceremony they led her deeper into the facility, Wei taking care to lock the heavy door behind them, which amused his counterpart. As they led her along, she had the chance to give them another look over. They both reminded her of the kind of people she had grown up around in her earliest memories, absentminded professors, the kind who could tell you Planck’s Constant to nine decimal points but couldn’t be trusted to remember to wear shoes. Those were her mother and father’s type of people; they were also, sadly, not the type who were likely to make it in the new world, and many of them had been lost. Only now in her own young adulthood had she come to truly value the core of toughness in her mother, who had shepherded her family through the darkest times, even as her father’s mental condition had deteriorated.

The two of them cut a comic figure, Carl tall and black and thin, Wei short and pudgy and somewhat doddering. They both wore the signs of middle age, and as they jawed at each other as they walked it was clear that they were a special kind of close, bickering friends. As they made their way through the complex she was relieved to find it much closer to a set of laboratories and workshops than a barracks. They garnered a few quizzical stares, and a few closed doors to hide their work as she passed, but she detected no obvious menace. As they moved through the winding structure, she saw perhaps a dozen of them, mostly clad in lab coats or coveralls, mostly around middle age, although there were a few younger converts. They were decidedly unthreatening. The reemergence of natural light, spilling in from above as they made their way out of the long corridors and into an open workshop area, also brightened her spirits. From time to time the ant symbol cropped up, painted on the walls.

In this wide space, she found herself both impressed and mildly disappointed. An old Jeep was raised up on a lift, with someone welding its frame underneath. Simply the presence of functioning welding equipment – and the electricity necessary to operate it – was remarkable. She kept a running inventory of the people she saw working. She noticed a perfect straight scar running down the arm of the welder, and thought she made out two small metal contact points on either side. She wondered if they all had prosthetics, though she had been surreptitiously probing Wei and could find no signs. Another set of workers (including one of the few women she had seen) was tinkering with another car’s computer, a wire leading into the hood connected to an IBM in a yellowing case. There were stacks of tires, many tools that looked rust-free, and a metal drum that she assumed was filled with fuel. Functioning cars were so rare in part because their precision engines were notoriously incompatible with gutter gas, which worked reliably in uncomplicated generator motors and old two-stroke engines but which contained impurities that could be lethal to a modern automobile. The shop was the envy of pretty much any she had seen.

But she could not help noting that they were just cars, and just a few of them, and nothing like the otherworldly tech of the Sanhedrin’s drone. Still, she had no idea how big this complex was, and she told herself that the really impressive things would probably be kept under wraps.

All the while Carl and Wei had gabbed to each other, mostly references that she couldn’t understand. She tried to decode what they were saying, but they spoke quietly and were moving quickly through loud spaces; the most she grasped was a few references to “over there,” which she guessed was the walled settlement in the world above. Finally, they came to a long, sloping staircase, elegant and refined, one which looked more at place with a mansion than a water treatment facility. Glancing back, she realized that at some point they had crossed into a very different kind of construction, with different flooring and walls, though she had not noticed in the distractions of the work going on around her. Glancing up the stairs, she could see natural light streaming in above, but they led her downstairs, not up.

When they reached the bottom floor, they seemed to clam up, their jovial bickering giving way to silence. She could feel tension between them. They led her down a hallway, until she could see a set of doors lying ahead. Carl pointed ahead of them.

“He’s down there, last door on your right.” His digital voice rang and echoed in the narrow hallway.

“Thanks,” she said nervously, gazing down the hallway. “Um, who is ‘he’?”

They looked surprised. Wei adjusted his glasses.

“Who are you here looking for?” he asked, as if the question had only just occurred to him.

“Dr. John Simon.”

“Oh,” said Carl. “Well, I’ll send him down here. But first you should meet the big man.” They waved her down the hall, then shuffled off quickly up the stairs. She said a silent prayer of thanks – Simon was alive, and he was here – and then for what felt like the thousandth time lately peered down a corridor into the unknown. She could hear the odd sound of musical notes coming from ahead of her, played at strange, disconnected intervals and with no tune or structure. She stood for a while, trying to make sense of it, but could detect no pattern. She walked over to the doorway. Next to the door, a simple sign read “MUSIC NODE.” Artificial light spilled from inside. She walked through.

“Hello?” she said.

“Come in,” came a wheezing voice.

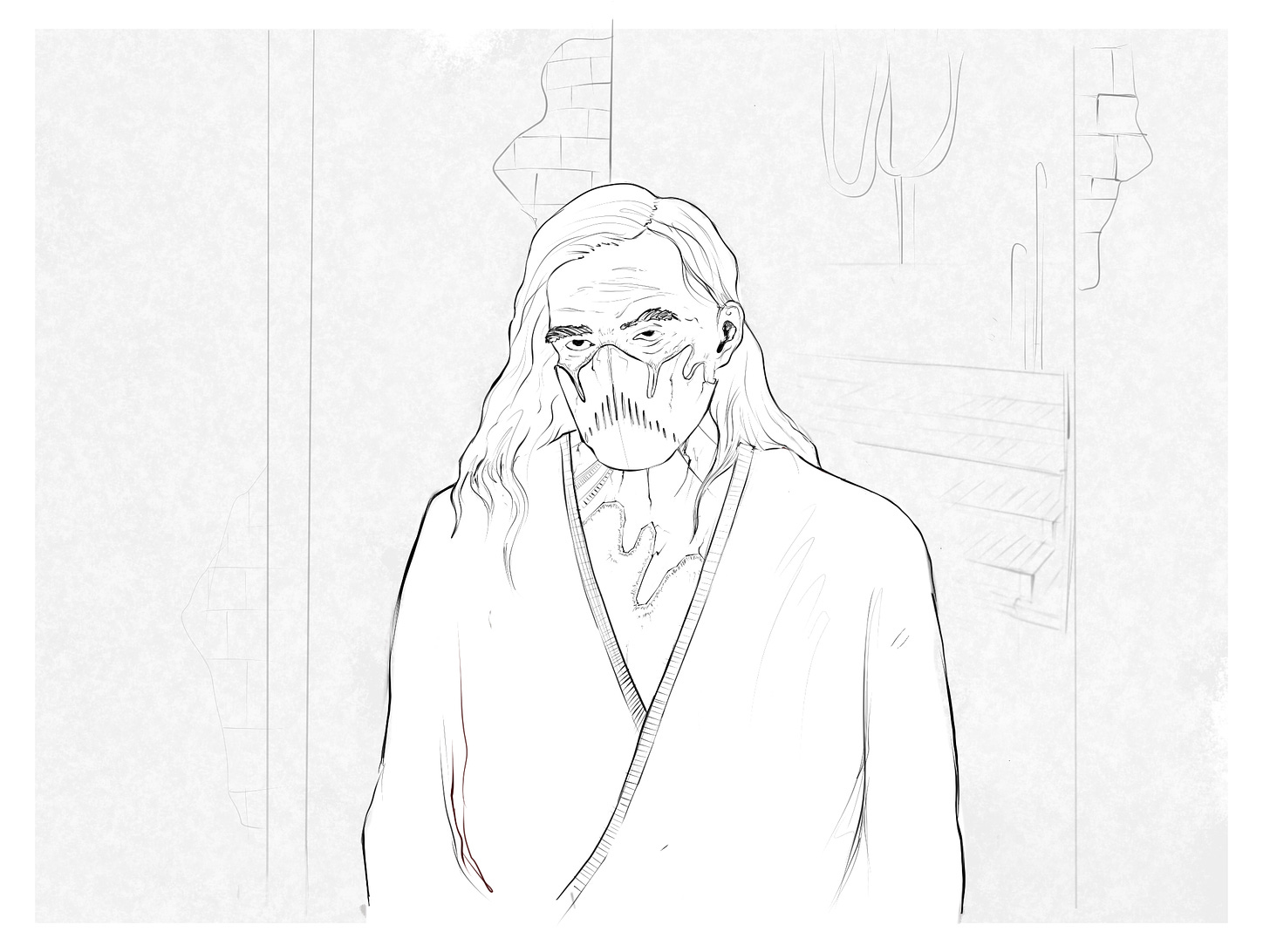

She found herself in a small electronics workshop. Speakers in various states of repair hung from the walls. An electric guitar with no strings sat on a worn wooden bench. Various keyboards, some of them liberated of much of their keys, lay about on the ground and counters. She spied a yellow multimeter that, in another time and place, she might have tried to steal. Across the room, in front of a large electric organ, crouched a cloaked figure, wrapped in a heavy cape-like garment, dark red and heavily weathered. Even bent over, he appeared tall. He was working with the electronic guts of the organ, then pressing keys to test them, turning his head as they rang out. A persistent hum lingered after each keypress, and he appeared to be trying to fix it, sighing irritably each time it rang out. She walked a few steps farther into the room, and he rose and turned towards her.

She stifled a gasp, sucking in to catch it before it could sound. Even having grown up around people with extensive prosthetics, his appearance shocked her. He was old, with long, flowing white hair. His forehead was etched with wrinkles and aging spots. And below his eyes, his entire lower face, nose and mouth and chin and all, had been replaced, a white polymer prosthesis that vaguely approximated a human jaw sunk gruesomely into his skin. A set of thin vents sat where his mouth once would have been. Beneath his artificial chin, his throat too was encased, or replaced, by the same polymer construction, which met the skin of his exposed chest in ragged and purple scars. His left arm was gone, and in its place was set a gleaming cybernetic limb of impossible intricacy, wires and pneumatic tubs and servos and actuators, all in the same chrome silver. On his other arm, stitched into the skin just below the crease of the inside of his elbow, was a catheter, the skin around it inflamed and flaking. Above his heart sat a pair of thick surgical scars set in a perfect cross. She stood, still and silent, taking him in for a moment.

“How can I help you, young lady?”

At a loss for words, she spoke out of a sudden impulse of pure curiosity.

“Your voice… is your real voice?”

He stared for a minute, then laughed, a short, endearing bark of wheezy and metallic laughter.

“Well, you are frank, aren’t you?” he said, taking a step forward and leaning on a nearby workbench with his prosthetic arm. “Yes, my own voice, more or less. The exhalation is manipulated by artificial instruments that approximate lips and a tongue, but it’s my own voice box, my own lungs, not that they’ve been treating me very well lately.”

He moved his hand up and touched his face prosthesis, reflexively.

“When you have as little of your own self left, you see, you tend to be proud of it,” he said.

He walked over towards her, extending his human hand. He moved hobblingly, with a gait that spoke of serious, old injuries, but there was real energy in his step.

“My name is Clay.”

“I’m Haojing. Haojing Wang.” He shook her hand warmly, and his eyes crinkled in what she imagined was a smile, but he gave no sign of recognizing her name. “Are you the leader of the Colony?”

He laughed, again, and again moved to touch his face, as if to scratch a chin that no longer existed to be scratched.

“I have been accused of that, yes. I try to forget it, but people keep on reminding me. A leader, please. Not the leader.”

As he spoke, she gazed over at a large stencil of the ant symbol that adorned the far wall.

“Ah, our mascot,” he said. “I confess I’m not a big fan. I wanted to use a starling.”

“You also wanted to call us ‘the Murmuration,’” came a voice from the doorway. In walked a middle-aged man in a threadbare suit. Tall and attractive, he looked far more put together than most of the other members of the Colony she had seen. He limped slightly as he came into the room, clutching a clipboard.

“I like birds,” said Clay with a shrug. “But I lost that vote, among many others. Ms. Haojing Wang, this is Dr. John Simon.”

Simon walked forward and shook her hand, holding the clipboard in his armpit while he did so. He smiled, and she blushed.

“How can I help you?” he asked. Standing in front of him, now, she felt sudden, intense anxiety, about how to ask and whether he would say yes.

“I – I’ve come a very long way to find you,” she said, her voice cracking.

“Do… do I know you?” he asked.

“No. But I think – I think the Colony knew my parents. Chien-yi Wang and Kai Chi Wang. I’m their oldest child.”

Clay gasped, a hollow sound that rang strangely in the small space.

“Oh, my dear. Oh, my,” said Clay, looking her over. “Yes, yes of course you are. You are their daughter. Oh, I’m so sorry. It’s been so long, I didn’t realize….”

“I don’t believe I ever met them,” said Simon, “but I can see they made quite an impression.”

“Yes,” said Clay, touching the scars above his heart. “Kai Chi was an old friend. His ingenuity and resourcefulness were true assets to us, in the early days, back when we were avoiding the government. Back when there was a government to avoid. And her mother was well-known to those of us trying to hold things together, in the early going. A fierce intellect.”

He chuckled, a noise like notes half-pressed on an accordion.

“I imagine it was quite a childhood.”

She blushed, then nodded in agreement, suddenly preoccupied with a question she could not avoid. She held the question in her mind for a long moment before she asked it. At last she admitted to herself that saving Long Fei was not the sole reason she had come all this way.

“Do you know – did my father die? Do you know if he died?” she said, in a quiet and monotone voice. “He left home, years and years ago, and never came back.”

Clay nodded slowly.

“I’m sorry. Yes, yes he is dead.” She bit her lip and turned to face the wall, unable to meet their eyes, feeling the last little pang of the inevitable pass. “His body was found perhaps 10 kilometers from here, by one of our scouts, many years ago. We thought it was from exposure, but who can say.”

He leaned over and offered his human hand. She hesitated a moment and then grasped it firmly. It felt warm and comforting.

“He was not well, not for a long time,” said Clay.

“Thank you,” she said, wiping away a tear. “I’m sorry. I – it’s good to know, at least.”

“How is your mother?” he asked.

“I’m afraid she’s gone now too,” she said. “That’s why I’m here. I need your help.”

Here she thought again about what to divulge, and decided there was no choice but to plunge on ahead.

“She was killed, in an attack by the Sanhedrin.”

She had thought that might invite a response, and she was not disappointed. The two of them locked eyes with each other, a look pregnant with energy and meaning. The keyboard’s errant hum, quiet and vague, pulsed on insistently.

“Well,” said Clay, grabbing his cloak and wrapping it around him, “you had better tell us everything.”

Table of Contents and instructions for subscribing to just this serialized novel here. Illustrations by Vika S. If you enjoy this novel, consider leaving a tip. Tips will be split equally between the author and illustrator. Sign up for fredrikdeboer.substack.com here.

©2019 Fredrik deBoer