Chapter 28

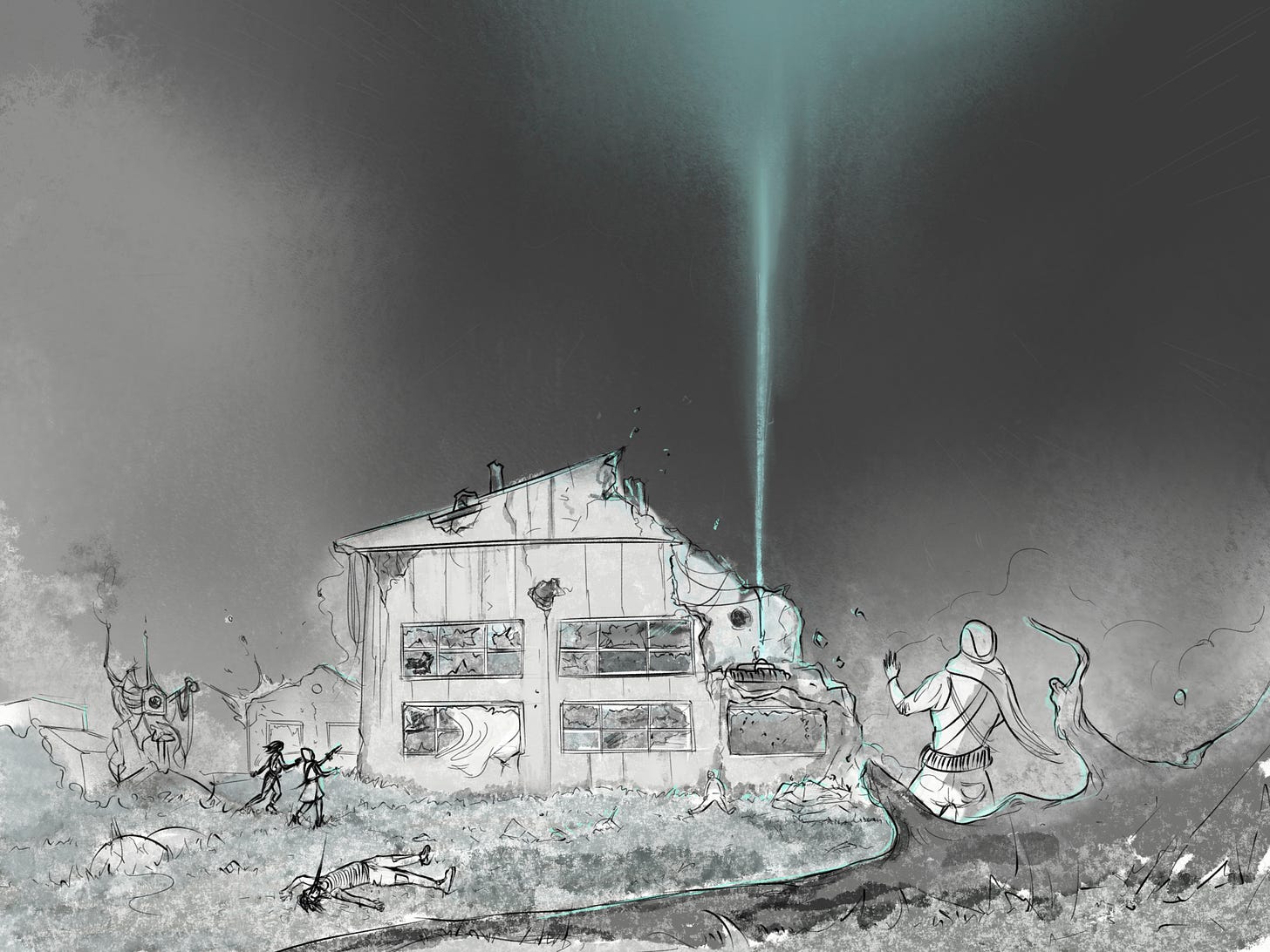

She clutched her brother’s lifeless body, screaming into the noise around her. He felt light and supple in her arms. She pressed his face into her chest and sobbed. The wind was now howling, the vibration seemed as strong as ever despite the number of downed drones, and the explosions and gunfire around her battered and dulled her senses. She sat exposed to all of it, surrounded by all of it, the war around her supremely indifferent to her brother, to her blinding rage and impossible grief, and so she screamed and screamed into the noise.

Clay moved into her range of vision, his white hair blowing behind him, red cape torn and filthy but somehow stately as it billowed behind him. He was holding a rifle like a handgun in his prosthetic arm, squeezing off rounds, and he looked beautiful to her in that state, like all of it was made just for him. And then he turned and saw her, saw Long Fei’s body in her lap, and he paused there looking at her. He stood above her and some meters away and hung there stock still for a moment as the battle burned around him. He regarded her with a look that she knew to be sorrow, true sorrow, for her and for her family. And then he turned, and he ran towards cover and shouted to his remaining troops, and he fired the rifle again, and in an instant she knew that he would never stop, that none of it would ever stop, and she knew what she had to do.

The drone that had carved out an opening in the second floor now laid twitching and sparking in the grass beside the building. At some point the house had caught on fire, and as she made her way up the stairs she hacked and choked on smoke. But she pressed on and in a moment she was in her father’s workshop. The EMP was even bigger than she remembered, awkward and immobile. But she found a clothesline among her father’s random baubles and was able to wrap it around the thick cylinder, and with one hand she tied a knot she had learned in this house a decade earlier, and when it was securely fastened she started to pull. She tried to pull with both hands at first, but the pain in her wrist was too intense, and so she was forced to use only one. She braced and heaved and dragged, and her little body felt like it would buckle underneath her, and bit by bit she inched it across the floor. Every tug was agony, and she felt exhaustion bone deep in her whole frame, and her hand was raw and bleeding, and the nicks and scrapes and pains of the past weeks all groaned out at her at once. But finally the EMP sat right up against the hole in the wall.

She stood beside it for a long moment, still taking in the scene. Now the Colony’s remaining troops seemed to be winning, and now the Sanhedrin, and now she thought they might all succeed in mutual destruction. But finally one of the troopers saw her, and he started to draw the attention of the others, and then one pointed at her to Clay. He looked up, and she could just make out his eyes above his smooth prosthesis, and they opened wide, in fear of her, and he screamed out to her to stop. And then she pulled the pin and was engulfed in energy and the world shook and everything went black.

When she came to a few minutes later, the carnage before her was complete. The vibration was gone. The gunshots had ceased. Even the wind had died down. She wandered downstairs, her mind blank and distant, and when she emerged into the yard she was greeted with almost perfect silence.

Around her, the remaining members of the Colony laid dead or dying, killed by the failure of whatever cybernetics had kept them alive. Drones, intact or destroyed, littered the yard. She stepped numbly past a young woman who was collapsed on her side, ant tattoo visible on her shoulder. Her arm flapped gruesomely beside her as her nervous system shut down, eyes rolling over into her head. Haojing looked around and found a submachine gun, grabbing it with the intent of ending the young woman’s pain. She grasped the barrel and it singed her fingers, hot from firing. She swore, then reached carefully for the grip, and turned back towards the woman. When she approached she found it was over anyway, and she tossed the gun back down beside her.

Nearby lay Clay’s body, his eyes still wide as dinner plates, blood pooling from his ears. It was then that she looked back at Long Fei’s body and remembered. She gazed at Long Fei’s body for a long while, dimly afraid that the house fire would spread and overtake his body. But already the fire smoldered and died. It occurred to her that the workshop she had coveted and feared her whole life was now gone.

From the corner of her eye she spotted movement, and she turned to see Simon, who looked at her in awed horror. He walked backwards away from her, stumbling, then ran off towards the horizon, empty handed. She watched him go, dimly sorry for him, and then heard gasps from nearby.

She found him crawling away from the mech. He was pudgy and pale and he wore glasses and a sweaty white shirt. He was covered in horrific burns, inflicted on him when the EMP had caused his mech’s electronics to fail and fire, cooking him in his cockpit. He dragged his lower half forward, using only his arms for motion, his legs unmoving. He crawled over to the fencepost, then grabbed it with his arms to pull himself unto a seated position. He slumped against the post, still gasping. He looked at her with empty eyes as she limped towards him.

“You – you didn’t – you didn’t give us a chance,” he said, gasping and stuttering from his burned longs. “Everything…. We could have – it would have been so much better….”

She kneeled down beside him. Aside from his voice, the world was quiet. She took his hand in hers and stared off into the sky.

“You didn’t give us a chance,” he said again, body convulsing.

“Shhhhhh,” she said. “Shhhhhh. It’s alright. Everything’s alright. Shhhhhh. Everything’s alright. It’s alright.”

She squeezed his hand and repeated the words, over and over, until long after he was dead.

Chapter 29

Mac’s farmhouse was as he had described it – hidden away, tucked in the corner of the woods on the rise of a mountain, a sturdy old brick structure with a thatched roof he had meticulously restored. There was a pasture for large animals and a garden ready to be seeded, even a well with a pump for drawing water as one needed. Nearby, a tall metal windmill turned above, slowly chopping its way through the air. As she gazed around at his land from on top of her horse, clutching her arm where it hung in its sling, she could not help thinking that the place was, in many ways, perfect for Mac. She had seen pictures like it in the old magazines her father kept piled around their home.

They had fled only a few day after the end of the battle. She had approached the neighbor’s house numbly and told her aunt and Mac that it was over and that Long Fei was dead. Her first instinct was to dig his grave herself, but it was impossible, and she was grateful for Mac for doing it for her. They decided, ultimately, that they could do nothing for the other casualties of the battle. They were determined to leave in short order, and there was no time or energy or able bodies to dig so many graves. She lingered over Clay’s body, unsure how she felt to see it lying there. Ultimately she unhooked his cape from his shoulders and laid it over him like a burial shroud. She would do nothing else for him.

They had left not long after. The village was a ghost town, for now, but she knew many would eventually return. She knew, as well, that the salvage remaining from the battle would be too enticing for the wrong kind of people, and that they had to leave before the first desperate scavengers arrived. The house was burned and broken, and the village was no longer friendly, and there was nothing left to keep them there. The other villagers were too afraid to approach yet, but in time they would come, and they would come with revenge on their minds. No one could avoid blaming the family for the battle, or for what followed it, even if they were ignorant of what had destroyed all of their technology. There could be no mistaking whose house that pulse of light had emerged from, and as modest as it may have been, that technology had been vital to their lives. Since she had pulled that pin, four people in the village had died. She tried, at times, to think of the thousands of miles the EMP would have covered, but she found that she could not conceive of such a thing, like a math problem where the numbers were all bigger than she could fit in her mind. All she knew was that, in her own world, it was all dead, everything with a battery or a screen, all of it, and forever.

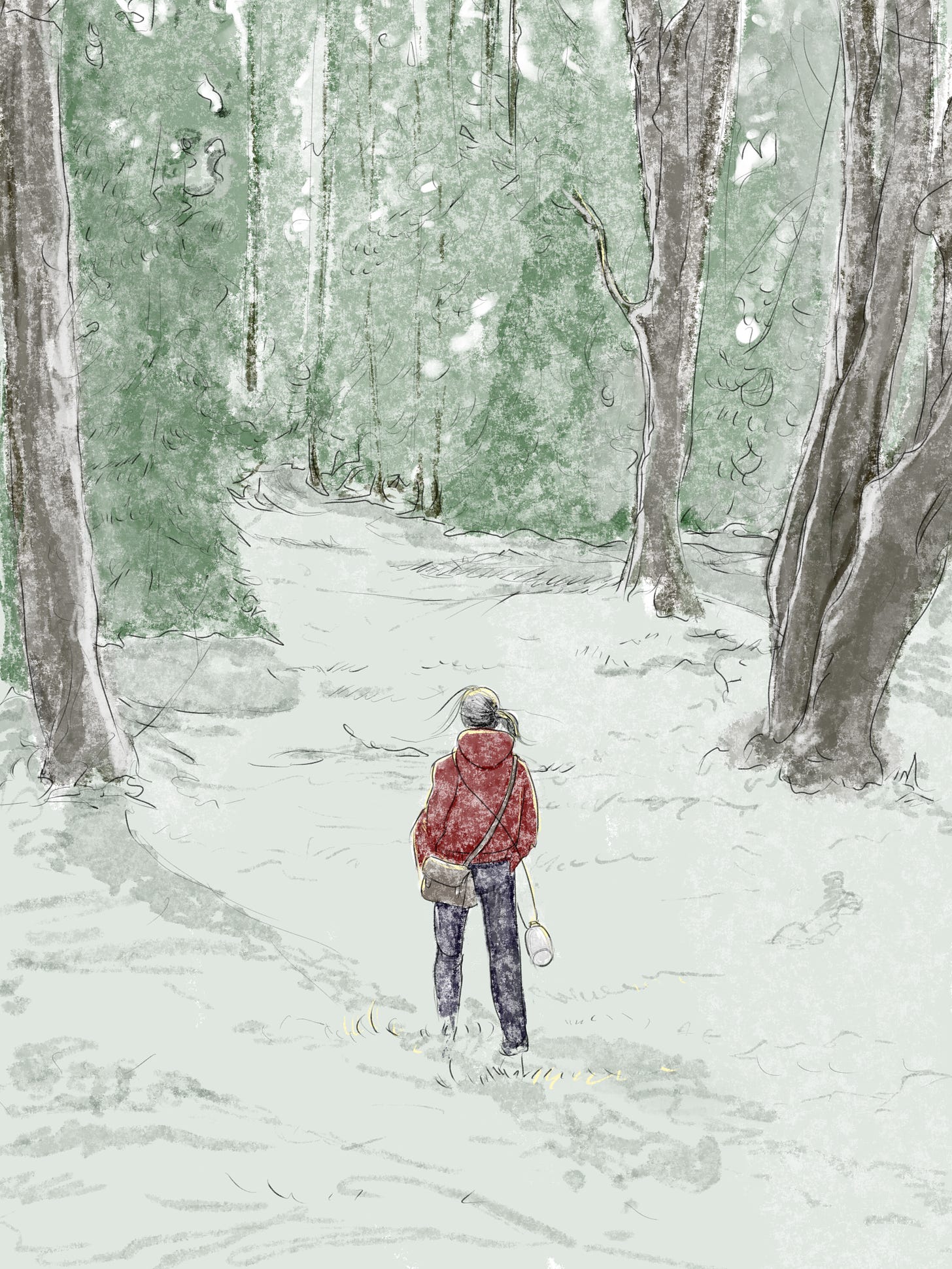

And so they had packed up the children and fled, taking what little they had left worth saving. They had traveled for a day to the home of a distant relative, who had taken them in with suspicion but without complaining. Mac had wanted to bring them all here, to his farmhouse, but Haojing had said no, and had sent him away, to wait for her. She stayed behind and helped her aunt get settled, told her she was leaving, then kissed every last boy on the forehead, loaded what she had left on her horse, and rode away.

Now she was dismounting in front of Mac’s home. Her wrist still hurt, and the bouncing and shaking from the ride had been slow agony, but she felt clearer than she had in ages. She had promised Mac she would come and visit him, and now she had kept that last promise.

He emerged from the house into the bright, cheery sunlight, and she thought he looked good, healthy and happy. He no longer kept his arm wrapped in a sling. He smiled at her, big and broad and sincere, and for a moment she wished that sincerity was all she still looked for in a smile. He embraced her, and though she did not let the reins fall from her hand, she hugged him back all the same. When he let her go, she brushed his hair from his face.

“What do you think?” he said.

“It’s lovely, Mac,” she said, with sincerity of her own.

“Stay,” he said. “Come live here with me.”

She started to shake her head, and he placed his hands delicately on her shoulders.

“Listen, I – we don’t have to – to be anything to each other,” he said. “Just stay here. Bring your family. There’s a space for all of us here. Food to grow. Room to run. We’ll just help each other, all of us, that’s all. You, your aunt, the boys, me. I’ll help them. I care about them. I care about all of them. I’ll help you. All I want is to help. Please, I have been preparing this place for someone. It’s perfect. We can stay here forever. Please, just stay.”

She looked at him for a moment. The day was almost too beautiful, and the sun breaking through the mountain trees peppered him in light, dappling his thick beard and broad shoulders.

“No,” she said.

She kissed him lightly on the forehead, then placed the reins in his hand.

“Take care of Jelly for me. I can’t ride him anymore.”

She turned and walked off, heading down the mountain. For a long while he watched her go. She took a circuitous path, avoiding straight lines, hiding where she could, doubling back, crawling across the mountainside away from him until she was a small speck in his vision. He stared down the path after her long after she had disappeared, heading someplace far far away. He shifted uncomfortably, unsure of what to do, until the horse brayed, and he turned and stroked its mane.

When he turned back towards the mountain view, he was unsure what had previously occupied his mind. Already the anxiety and sadness of Haojing’s rejection had left him. He looked around at his home and felt satisfied, content in what it was, in what it had to offer. Soon he would lay seeds in the garden, and after that, the harvest. Everything he needed was in the place where it belonged, and someday, he knew, someone would come. He turned and led Jelly to the pasture, and all that was left in that spot was a slowly twisting windmill, rusted but stout, turning lazily beneath a brilliant blue sky.

The End