It spilled out of her, quickly, in long streams of unbroken monologue. In part it just felt good to talk to someone again. They had moved to Clay’s private quarters, a large but utilitarian space in the top floor of the complex. The broad windows looked out at the landscape facing the river, away from the walled city, although the haze of smoke still clung to the view. As she talked Clay had expressed sympathy when she had reached the difficult parts of her story, but otherwise allowed her to speak uninterrupted. He had offered her coffee, which she gladly accepted, and as she was unused to caffeine her heart raced as she spoke.

Clay was seated in a kind of crude, low-slung hammock in front of her, which he said helped his back. Dr. Simon sat at a table near her, with a laptop in front of him that he tapped at from time to time as she spoke, an extension cord running out the door and out somewhere in the depths of the facility. A younger man Clay had identified only as an assistant sat nearby but did not speak. The room was filled with old books, many unusually well-preserved, and a raft of yellowing papers. A weathered black trunk with a faceplate that read “H. CLAY” on it sat in the corner, and on top of it sat various knick-knacks and mementos – a brass sextant, a clay giraffe, a diploma still rolled and wrapped in a fading red ribbon. The room was lit by a set of neon tube lamps set into the ceiling above.

When she had finished talking, and ended her story, she felt physically spent, drained. But she also felt that a weight had lifted, and it struck her that part of her burden had been that no one really knew what she was going through. Afterwards they sat silently for a while, with only the sound of Dr. Simon’s typing to puncture the silence.

“Now perhaps it’s fair if we give you information in return,” said Clay. “What would you like to know?”

“The Sanhedrin… you’ve heard of them.”

He nodded, slowly.

“Yes. Yes, I am afraid they are something of an obsession of ours. Of mine.”

“Who are they?”

He rose from his hammock, which was not an uncomplicated proposition. When he was finally upright he limped over to the window and gazed out of it as he spoke, leaning heavily on the sill.

“They are like us, in many ways. They are men of great principle. And considerable resources. Considerable resources.”

He shifted his weight from foot to foot as he spoke, rocking slowly.

“They are… experts. In all the meanings of that word. They are men who have always known what to do. When things begin to fall apart, they told everyone just what to do, how to survive, how to fix the world. They might even have been right, you know, about what to do. But they were always angry that no one would listen. Over time they grew less and less willing to take no for an answer.”

“Where do they – do they have a base?”

“No one knows where they are located, precisely, but the patterns of their probes and drones and vehicles suggests that there is surely a center hub somewhere, likely far to the west. There are also rumors of substations, automated outposts, but we have crawled across the landscape for years and found no trace.”

“But you knew them once.”

“After a fashion. I knew some of the men who became their leadership, when they first formed their group. Those were… complicated times. No one knew that these loose groups would become real factions. Everyone fancied themselves a revolutionary in those days. The biggest, most well-funded, most coordinated groups would shrivel and die; small bands of idealists with no coherent politics at all would flourish. You just never knew. I knew they were serious, but I never knew they had the capacity to become so….”

He paused.

“…uncompromising,” he said. “Now, our information comes largely from regular people who have spotted their machinery, or from those who have captured or salvaged it. Beyond that….”

He trailed off again, staring out the window. He seemed to constantly have to regain control of his own attention, to bring himself back to the room around him. He reminded her of her father.

“And they want technology all to themselves?”

“It’s not that simple. Not that vulgar. They believed that, after everything that happened, regular people had to be sheltered from the responsibility. They have to be saved.”

She glanced over at Dr. Simon, who was still staring into his computer screen, unmoving.

“What do you believe?”

He snorted.

“I was one of them. Not one of the Sanhedrin, no. But one of those who looked down from the world above, sorting it into spreadsheet cells under the delusion that if I understood it I could manage it. It turned out we couldn’t, none of us. And now there’s been a great leveling, one wrought from chaos and disaster, and the same old forces are marshalling under the influence of the same old delusion.”

Haojing frowned.

“I mean…. I guess it’s just hard to imagine anyone taking control. Even them.”

Clay turned from the window and faced her. He hunched against the window sill, silhouetted by the sun coming in through the glass.

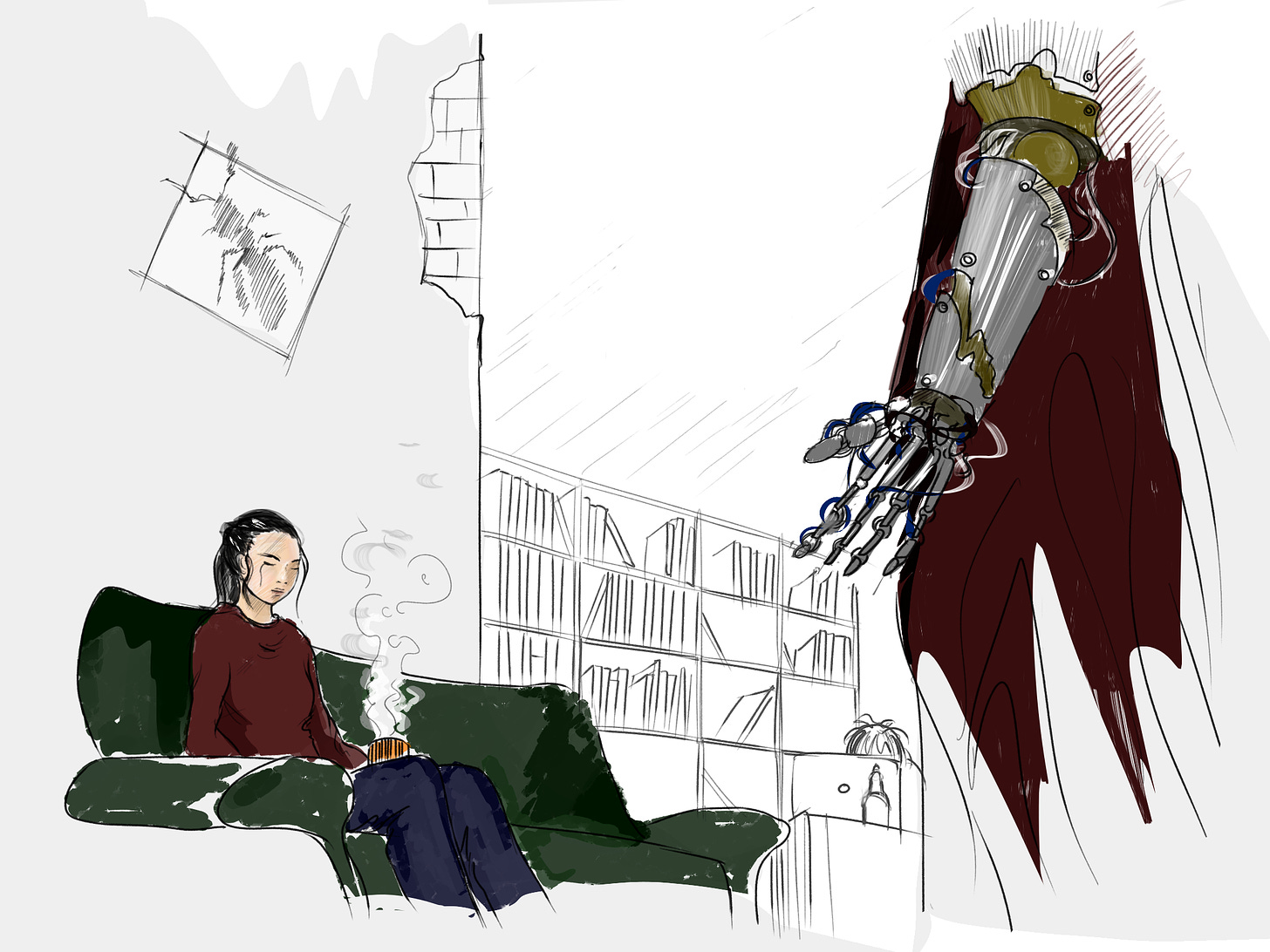

“I prefer to be out ahead of things. And,” he said ruefully, holding up his prosthetic arm, “I suppose I have a vested interest in keeping technology in the hands of the people.”

“Do all of your people have cybernetics?”

“Not all, no. John here doesn’t. Wei, who you met, does not. Several others. But, yes, most of us. It was a way we found each other, the source of our bond. People like John, who had worked for years to make us what we are; people like me, who could not be here without them. We find ourselves uniquely advantaged in this new world, and uniquely vulnerable.”

“What is your plan? What does your group do?”

Though it was a minor thing, she noticed Simon shuffle uncomfortably in his seat, still staring into his screen.

“We have plans. We have plans. But we are not presently equipped to execute them. We need energy.”

She glanced around the room, at the light, at Simon’s computer, at a heater plugged into the wall.

“Don’t you already have energy? This facility, I’m not sure I’ve ever seen more.”

Here Clay wandered back over to his hammock seat, and fell into it, again with clear effort and discomfort.

“I’m afraid what you’re seeing here is not sustainable, and certainly not something we can build on. You see, we are… borrowing the electricity here.”

“The walled city.”

He nodded, staring off into space.

“Yes. We found a way to tap their lines, years and years ago. It was always intended as a temporary fix. We kept trying to develop our own production capabilities. Solar power. Wind. Nothing worked. Not at scale, anyway.”

“That water wheel, out on the tributary?”

He let out another snort, or whatever the equivalent of a snort is for someone without a nose.

“A particularly frustrating failed attempt, yes. Although given that the river ended up moving I suppose it might have been for the best. My lot in life: we have too many scientists. Not enough engineers.”

Simon looked up from laptop.

“You recruited us, asshole,” he said.

Clay laughed, a barking, wheezing cackle.

“Yes. Yes, I’m afraid the fault, as usual, is mine. In any event…. They will eventually discover that we have tapped their lines. Our power draw is already too high to avoid detection forever. And I fear that when they do, they will seek retribution among the people of the settlement above. It’s wrong for us to expose them to that risk.”

He sighed.

“Besides, we are already straining the capacity of the lines we’ve tapped. And I always intend for us to be builders, not….”

“Scavengers?” said Haojing.

“Oh, I wish we were scavengers,” said Clay. “Scavengers are noble animals. They fulfill an essential function. In today’s world it is the job of all of us to be scavengers. We have to crawl across the land, looking for what can be useful among the things left behind. We have to build a new world out of the scraps of the old. No, here we are parasites, I’m afraid, and that’s something else entirely.”

“So you need your own source of energy.”

“Yes.”

“… like the Sanhedrin have.”

He nodded.

“Yes. So we assume. We have recovered several of their autonomous vehicles, both through capturing ourselves and bartering with others who have salvaged them. Their technology is impressive but they run off of fairly conventional batteries. Which means they must be generating electricity at the source, and at great scale.”

“And you want it.”

“We need it,” he said. “You see, we are dying. I am dying. Like your brother. Our implants are slowly failing. To fix them will take computing power, at large scales, and for that we need energy.”

“What are you going to do, with the Sanhedrin? Fight them? Try to negotiate with them?”

For a long while he sat in silent. She studied him, but without a face she could not read his mood. Finally he nodded to himself, several times.

“You do cut to it, don’t you,” he said. “That’s your mother in you. Well, perhaps it’s enough to tell you that we have plans in place.”

He turned where he sat and addressed Simon.

“And in the more immediate term, we have someone who needs our help,” Clay said. “Can we help this young lady and her brother, John?”

He tapped at the keyboard, then nodded slowly. Haojing’s heart skipped.

“I think so,” he said. “Please understand that I haven’t worked with a Kurosagi in many years. So few of the people who needed them survived. But, yes. Yes, I think I can help you. That is within my abilities.”

She flushed, and cried again, and again felt ashamed. She had cried more in the past few weeks than she had since she was a child. But she could not hold them back, and after a moment she felt anger at her own shame, and let them loose, and wept openly and loudly. Clay’s assistant stirred, and seemed like he would rise to comfort her, but Clay put his hand gently on his shoulder to dissuade him, and for that she was grateful. She let out great gasping peals of tears, until they gradually ran out, and she sat for a while breathing heavily.

“Can you give it to me in a script, something portable?” she asked Simon.

He frowned.

“Well –”

“We will, of course, come to you,” said Clay, quickly and evenly. “It would be our pleasure.”

“Thank you,” she said. “It’s some distance away.”

“Well, to tell you the truth,” said Clay, “I’ve been looking to get out of the house.”

She turned in her seat, hands on her knees, eyes on the floor.

“How can I ever repay you?”

He and Simon again made eye contact.

“Ah. Well….” He sighed. “I have a favor to ask.”

Table of Contents and instructions for subscribing to just this serialized novel here. Illustrations by Vika S. If you enjoy this novel, consider leaving a tip. Tips will be split equally between the author and illustrator. Sign up for fredrikdeboer.substack.com here.

©2019 Fredrik deBoer