Chien-yi died a few days later. They had barely spoken since; she had no energy to speak, and then she was too ill to sit up. She went slowly, and then all at once. When their mother was gone she and Long Fei had mourned for a little while, and then they had gathered the boys together and she had told them, and they all cried together, and then she and Long Fei put all of them to bed, one by one. The next morning the two of them dug a grave next to her garden.

As she washed the dirt from her hands, running the spigot from a backyard rain catcher, a small bead of guilt made its way up the back of her neck, growing while it did until it was the size and shape of a walnut. It deposited itself in the back of her head, and when she would think of her mother in the days ahead she would feed it and it would grow.

The days that followed felt strange and quiet. Those few villagers that she knew by name had expressed condolences, but had kept their distance. Paranoia and distrust were constant those days and as long as she could remember her family had been seen as the crazy old inventors at the edge of town. Still, it hurt her to think of all the times her mother had helped those around them who now were nowhere to be found.

She had taken the time to sit with every child, cajoling them to slow down for a moment and sit on her lap. She would wrap their little hands in hers and remind them that her mother had loved them very much, and she would tell them all the little things she liked about them. They would bounce and swivel in her lap but did not resist her holding their hands and when they rose to go she would kiss them on their foreheads with a mother’s kiss.

Long Fei had sorted through every last scrap of the drone. He had attacked the project with passion. It had allowed him, Haojing was sure, to set aside his grief and his own physical discomfort. He was ultimately disappointed, as there was much to examine but little to salvage; the parts were all proprietary, purpose-made, of little use in a world of cobbled-together parts. He felt certain that the drone had been made decades early and hidden away, preserved. No matter how advanced the Sanhedrin might be, no one could fabricate such a thing these days.

She was sitting on a stool next to him as he went through all the components, labelling them, describing their function. As a child he had been an insatiable troubleshooter and tinkerer, endlessly disassembling and reassembling whatever machinery was present in his environment. Their father had encouraged the practice, which annoyed their mother, largely because Long Fei’s talent for taking things apart was not always matched by his talent for putting them back together. She had never seen her mother more angry than when she came home to find him removing the case from his implant’s hub.

She had not been paying much attention to him, as he listed and labeled parts of the drone, its propulsion mechanism, its sensors, its engine. She was contemplating the trip ahead of her. But he had turned to her, expectantly, holding a thin bronze sheet up in the air for her to see.

“It’s the antenna,” he said quietly. “It’s how it communicated with… them.”

He was holding it delicately between his fingers, examining its design. He half turned towards her but did not take his eyes from the antenna.

“They’re going to come back. Aren’t they? They’re going to come back here.”

“Yes. I think so. Mother thought so.”

“I’m endangering us,” he said simply. “We could leave if not for me.”

She shook her head, sharply.

“No. This is our home. We would stay and defend it either way.” She did not want to lie to him, but she couldn’t think of what else to say. He set the antenna down and continued to paw through the parts.

“I’m leaving, for a while. I’m going to look for help. At least a week. Maybe a month or more, I don’t know. I need you to help look after things while I’m gone.”

“Alright,” he said.

“Now show me how those propellers work,” she said, and for the next hour it was like when they were children, putting things back together, learning how they worked.

The next day Haojing’s aunt had come, and as usual she helped without complaining, and as usual to Haojing she was very cold. The boys were about as well behaved as they were capable of, for which she was grateful. Mac, to his credit, had been genuinely helpful, present but silent. It was only when she told him her plan that he had something to say.

“Are you out of your fucking mind?”

She was not particularly surprised by his reaction. It was, she was fairly certain, how she would have reacted herself, had the situation been reversed. But she was not about to let him know that, so she simply continued packing her bag.

“First of all, for all we know Big Flat is a myth. You’re talking about an 120 kilometers walk, and you might get out there and find that it’s all bullshit. And if it’s not bullshit, that might be even worse!”

Haojing was digging around in her cupboard, looking for a few essential items. She had already packed a first aid kit, a road flare to scare off animals, one precious can of anti-bear pepper spray, a pair of scratched up aviator sunglasses.

“How am I doing for weight?” she asked him distractedly as she dug around. She came up with a dented airhorn, considered it for a moment, then threw it over her shoulder.

“You’re not even listening to me,” he said gruffly, then lifted her bag with his good arm. “You’re getting there. A couple more pounds. Five at the most.”

“Listen,” she said, rolling some socks up into a ball, “my mother wouldn’t have sent me out there if it didn’t exist.”

“I’m sure she wouldn’t. But when was the last time she left this village? How can you know it’s still… uh, alive? Or whatever.”

She stopped, sighing, letting her shoulders fall. She looked at him in exhaustion.

“I don’t, Mac. I don’t know. But I have to do something.”

He nodded.

“I’m sorry. I don’t mean to give you a hard time.”

“It’s alright,” she said, turning back to her bag.

“Well, I’m coming with you,” he said.

“Absolutely not,” she said, zipping up her bag and walking briskly out of the room, towards the kitchen.

“Do you know what’s out there, up north?” he said, puffing behind her. “I know you’re tough and I know you can take care of yourself. But it’s different up there.”

She pawed through the cabinets, grabbing at some jerky her mother had made, ancient crackers in a yellowing cellophane packet, vitamins they had scavenged from an abandoned health food store. Mac leaned against the counter and tried his best to sound reasonable.

“There are a lot of bad men up there. Desperate men.”

She zipped up her bag.

“I know. And I know you mean well. But you’d be a liability out there, and I need you here.”

“I am not a liability,” he said, shuffling his feet in a way that, she had learned, meant he was feeling insecure.

“Here, catch,” she said, tossing a plastic container from the counter to him. He lunged clumsily for it, his good arm swinging up to try and grab it. His broken arm drooped in its sling, and he grimaced in pain. The container clattered to the ground.

He cast his eyes down.

“I’ll be alright,” she said. “And I’m not kidding. My aunt is… fine. But she’s not my mother. Long Fei will do what he can. But I need you to stick around, look after things. Help out with the boys.”

“What am I supposed to do with a bunch of kids?”

“I thought you wanted to be a family man,” she said, throwing her backpack onto her shoulders to test its weight. “It’ll be good practice.”

“Alright. Alright.” He cradled his arm in its sling, which was healing poorly. “You know you can’t – it’s not all bullshit, you know. There are threats out there. You might not come back.”

“I know,” she said quietly. “I get it. I know.”

“You know they say it – I don’t know – they say it processes people. For energy.”

“Well that’s bullshit,” Haojing said curtly. “Human beings aren’t any good as sources of energy. Not for a computer. I read all about it.”

“Can’t we just travel to my place? It’s great. Really. I want you to see it. I’m happy to share it with your family.”

“Long Fei cannot travel. Not even for a few hours. This is my home. I’m going to get help, and everything’s going to be fine.”

With that she strode out, towards her own room to nap. She tried to walk boldly, to express the bravery she did not quite feel. As she laid in bed she cradled her the back of her head in her hands and felt like she could almost feel the bubble of her shame, physical, with her fingers. She thought of Mac and his ruined body. She thought of Long Fei and the sincerity and power of his self belief. She thought of mother and the way her life had decayed away in front of her. And then she thought of herself, pinned once again between her desire for freedom and her responsibility, only now each was heightened, intensified. And then she thought of her father, and suddenly was asleep.

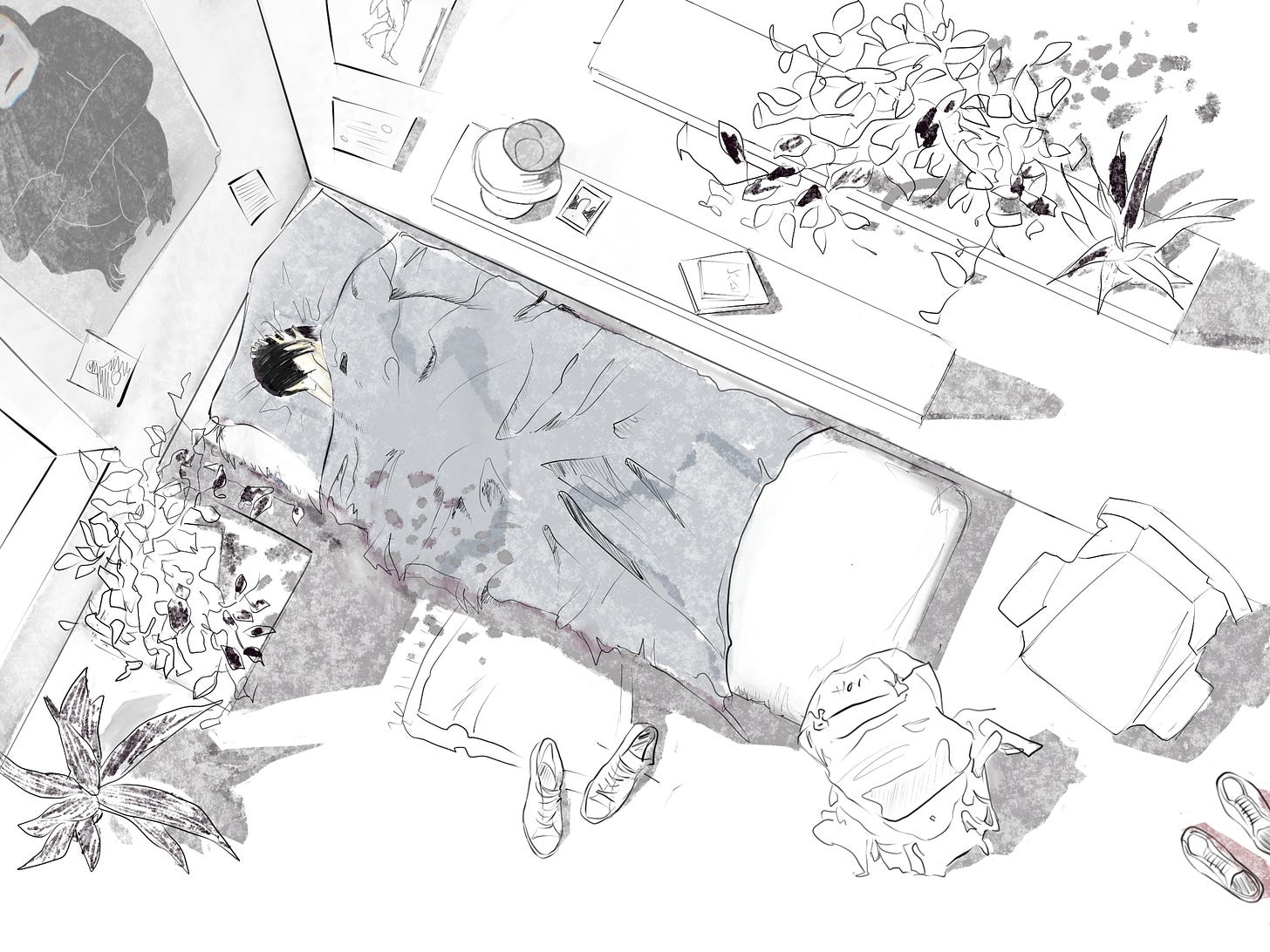

Table of Contents and instructions for subscribing to just this serialized novel here. Illustrations by Vika S. If you enjoy this novel, consider leaving a tip. Tips will be split equally between the author and illustrator. Sign up for fredrikdeboer.substack.com here.

©2019 Fredrik deBoer