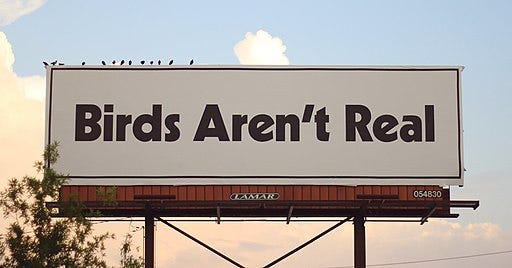

So there’s this “birds aren’t real” thing. It’s an intentionally ridiculous conspiracy theory that suggests the birds you see are in fact drones built by the government, meant to skewer conservative conspiracy theories like QAnon or Pizzagate. Here is a painfully stilted exchange between a 60 Minutes reporter and the founder of the “movement,” Peter McIndoe.

I have several complaints.

This is aggressively, aggressively unfunny. This kid doesn’t have much discernible talent and just isn’t very good at what he’s doing. I’m not trying to be a dick but you can look at his other appearances and see for yourself.

Good parody almost always works against official narratives, to the detriment of sanctimony, and without sanction by the priestly castes of society. This does the opposite - it flatters the establishment, is dripping with pompous superiority, and seems specifically designed to earn praise from people who stream the NPR app from their iPads to their tasteful Bose speakers.

The people who fall for conservative conspiracy theories are almost always those who are deeply sensitive to the perception that they’re being looked down on by liberal elites. Indeed, many of them gravitate towards out-there theories precisely because of resentment towards that elitism and a feeling that establishment media has nothing for them. So we… go on 60 Minutes and mock the rubes? How does that reduce the attraction of conspiracy theories, exactly? Who is this for?

Conspiracy theory is uniquely ill-suited to parody.

This last point is worth exploring. Parody, which is distinct from satire, involves accentuating the parodied object’s attributes in some way, manipulating its image to bring specific characteristics into relief. This often results in the techniques of caricature or the grotesque, which is to say exaggerating to the point of rendering something ridiculous or disturbing, but it needn’t always. Pulling out the individual elements of a person or piece of art or political tendency helps to show how the whole facade hangs together, and in doing so often undermines its seriousness to comedic effect.

The trouble is that, first, QAnon and related conspiracies are already exaggerated, already distended, and crucially, those who gain currency in conspiracy theory circles are those who go bigger. What I mean is that, in these communities, very rarely does someone gain social standing or influence by expressing a theory that is less grand or more plausible. They get clout by taking the theory to 11. My experience in current conservative theory spaces is limited, but my sense is that this is even more true there than in left-coded cultures like 9/11 trutherism. And the result is something like QAnon, which grows only more insane and larger than life over time - “the President of the United States is communicating via obscure internet message boards for some reason” is something I could see the more out-there JFK theorists believing. “He does so to warn us that elites literally eat children” is not. And so the “birds aren’t real” parody feels toothless, to me, as that’s not particularly exaggerated compared to the real thing, and anyway since that culture always wants to climb one rung higher you can never outrun them.

What’s more, for parody to reach the level of satire there has to be some sense in which it appeals to a moral consciousness, a level of communal understanding of where the ridiculous begins. When some political figure is parodied and they don’t like it, the discomfort comes from the fact that they have been exposed - the aspect of themselves or their project that has been satirized is now better understood by the public, more subject to the public’s scrutiny, and they are made vulnerable by this. I’m not suggesting that effective satire always has to be intended to have some political effect, let alone that it has to achieve such an effect. But satire always involves reference to a shared sensibility, an assumption that what’s revealed to be ridiculous will be mutually understood to be ridiculous. Conspiracy theorists actively reject the approval of the societies that satire aspires to reach, and will always believe that satirical criticism or any other kind is the work of the shadowy forces that control the world. The emotional animal spirits that underpin the conspiracy theory phenomenon is the desire to create a counter-public that rejects everything the dominant-public feels and believes. They don’t want to be taken seriously by the man. So what’s the point?

Finally, these conservative conspiracy theories are very fervently believed by some, but are also embraced with raised eyebrows and quotation marks by many of their “adherents.” This is 4Chan political economy we’re talking about here; nothing, not even racism and anti-Semitism, is expressed in a truly sincere spirit. And baked into this attitude is a permanent uncertainty about just what they really believe and what they don’t. It’s the kind of wiggle room you see a lot in contemporary culture, where just enough humor and winking is built into everything that criticism becomes impossible. It reminds me very much of how shitty movies, all too aware of the “so bad it’s good” trope, will now drop in some obviously self-parodic elements to ensure that they appear in on the joke - which of course destroys the sincerity that makes a bad movie fun to watch. (Mystery Science Theater 3000 would have nothing to say about Sharknado.) The Airplane! series had the perfect target in the disaster movies of the 1970s, as these were impossibly portentous, self-serious affairs. QAnon is no doubt believed in very ardently by some deeply unwell Arkansas 50-somethings, but the heavy lifting of the actual theories was done by shitposters who have marinated in internet irony so long they have no sense of what true belief would feel like.

In this sense, I suspect, they are like Peter McIndoe. I’m sure he’s a good kid, and I’m confident he’ll get bored of this soon and hopefully move on to a more worthwhile project. But just as with the Gravel teens, my deeply felt belief is that McIndoe is contributing to the very tendency he thinks he’s lampooning. The absolute last thing the contemporary American left-of-center needs in 2022 is to retreat even more fully into internet-poisoned insularity and mocking snarkasm. You cannot out-irony the alt-right, who have lost influence in the sense that the media writes less breathless essays about them but have gained it in the sense that they have filtered out into the official conservative apparatus themselves. I don’t know what to do with the QAnon impulse - it strikes me as a problem from hell, part of the internet’s terrible endowment to us, and I don’t for a minute believe that patient and respectful education would work, either. But “birds aren’t real” is emblematic of left culture in that it can only ever speak to those who enjoy it because it affirms the superiority they already feel.

I look out at the American socialist project and, while I see thousands of dedicated organizers and thinkers and groups, they’re obscured by a public face made up of a few hundred smirking white dudes, layering on more and more irony in their Twitter feeds before telling you to hit up the Patreon for their aggressively unfunny podcasts. You can do better, Peter.

Left/liberal conspiracies theories I am aware of:

1. Donald Trump tried to steal USPS mailboxes before the election.

2. Cops are performing genocide on black men.

3. Murder of black trans women is frequent and pervasive.

4. Virtually every zoomer and millennial online believe qanon levels of pedophilia exist among Hollywood and east coast elites.

5. Most “Bernie-types” ( for lack of a better term) believe ( unknowingly) everything conspiracy theory about the Clinton’s that Richard Mellon Scaife funded.

6. Gender and biological origins of sex are dreamed up by the patriarchy to suppress people.

I could go on, but I have my day to begin. Birds aren’t real as a parody is just dumb vs a one line stale Reddit joke that outlasted it’s time.

If Birds Aren't Real Guy did literally any research on the matter, he'd know that expert consensus is clear: you can't reason people out of an unreasonable position, and any extreme belief community worth its salt already has built-in defense mechanisms against outside disapproval. "Outsiders will shun and mock you because they fear your new power!" is, like, Cults/Conspiracies/MLMs/Crypto 101.

If you want to get people out, you have to solve the root causes: economic distress, fragmented communities, and institutional collapse. Flat earthers don't give a shit about Neil DeGrasse Tyson, but when you give them meaningful jobs that pay well, communities they can love and be loved by, and institutions that are effective at the local level, folks suddenly have a lot less interest in owning the spherehead libs. If Birds Aren't Real Guy wants to really make a difference, he should join a union or become a youth pastor.