Be a Writer or Don't Be One

the only person you hurt by ironizing your profession is you

This is one where you’re just going to have to trust me that the phenomenon I’m discussing is real. I could harvest tweets, in which case people will accuse me of targeting people and of being obsessive, or I can just assert that this is real, and people will dismiss it as lacking in documentation. I choose the latter.

Back in grad school, I found myself in some trouble after telling some peers (online) that they should commit to doing what they were doing or else quit. I was fond of almost every single one of my peers in grad school, but there was a disquieting tendency I observed where many of them seemed to be getting advanced degrees in the humanities with tongue partially in cheek. They went through the motions of academia, some of them to considerable success, but always did everything with half a foot in and half a foot out. I’m not trying to be arch, here. In terms of observable behavior this amounted to a tendency to treat as a joke all of the elements required of an academic career - “I’m sprucing up my CV lol,” “time to pretend to teach students pretending to learn,” “I’m writing my dissertation so it’s time to fake enthusiasm about reading 18th century short stories by women.” The origins of this behavior are not hard to divine: though my particular PhD program had a sterling record for getting graduates good jobs, others in the larger department did not, and anyway the casual brutality of the academic job market affected us all psychologically. The people who refused to really emotionally commit, the ones who gave themselves the out of saying that they had never really been doing it seriously in the first place, were doing so in anticipation of failure in a notoriously unfair and demeaning job market.

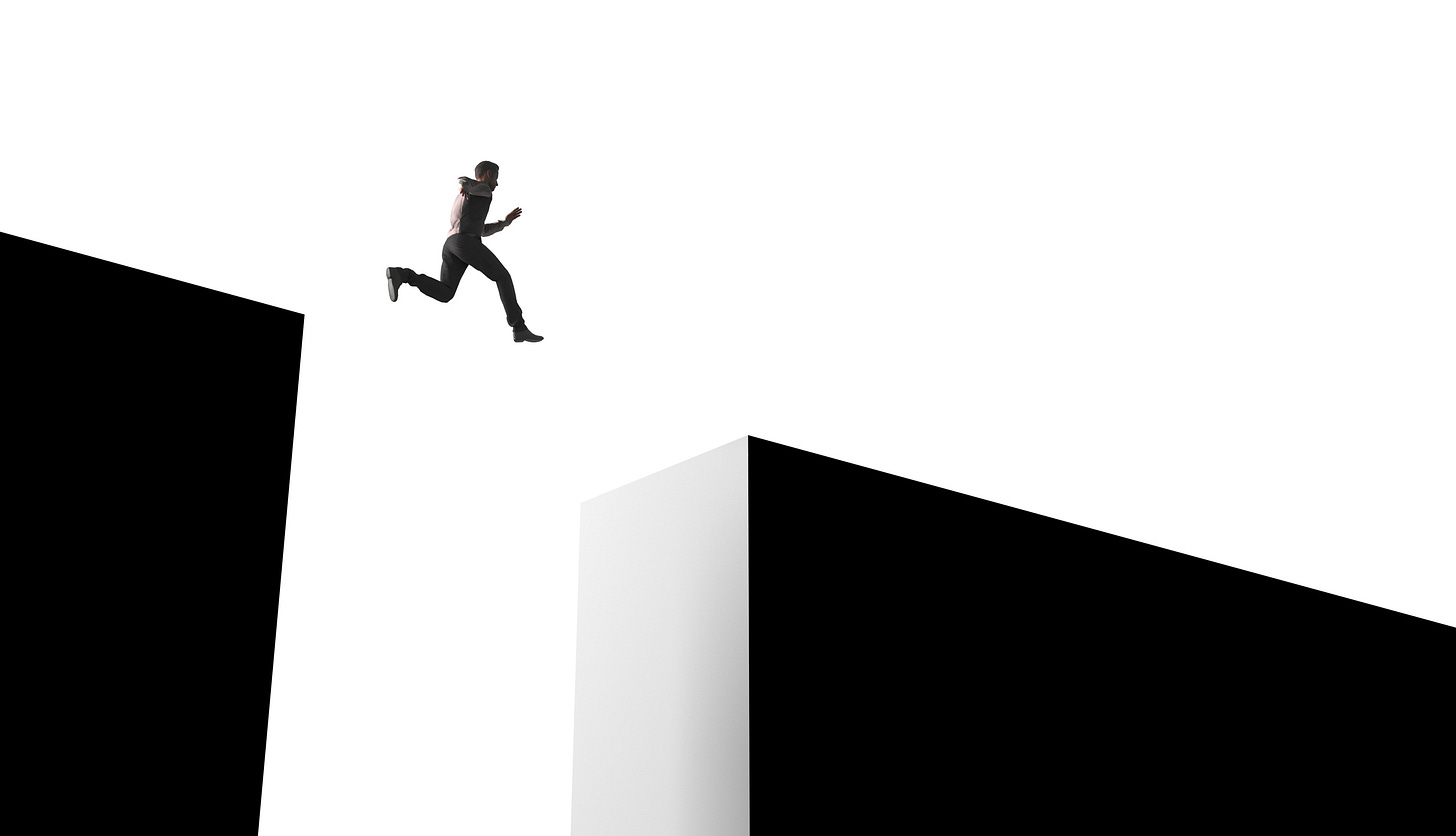

My point, back then, was that this is in fact not a good strategy at all. There’s lots of criticisms you can make about grad school, but you can’t say it’s not hard. The reading is intense and the writing is more intense, at least at most places. And I think that you can’t survive it unless you commit to doing what you’re doing, unless you permit yourself the vulnerability that comes with unapologetic effort. It’s just too difficult otherwise, especially because of the terrible money involved and the constant temptation to take on more debt you won’t be able to repay. If you can’t summon reserves based on some sense that you’re committed to what you’re doing in a deeper way, that it has some meaning for you, you’ll burn up or out. So commit to doing it or quit, for your own sake.

You may be able to anticipate the nature of the backlash. Some (again, online) claimed that I was endorsing the system, that I was telling people not to complain about the straightforwardly exploitative grad school system, that I was being an apologist for the absurdity and offhanded cruelty of the academic job market. But that wasn’t what I was saying at all. I had in fact criticized the working conditions of PhD students and the job market many times, in person and in writing, and would again. Saying that people should choose to be in it or choose to be out of it did not mean that they shouldn’t complain. It meant that if they did complain they should do so as people who were working within the system and were attempting to build a life within it without irony, outside of a self-defensive crouch. In fact I think criticizing from a position of sincerity will always be more meaningful than doing so from a position of denial. Besides - that style of self-defense is no defense at all. When you go out on the job market, trying to get a foothold into at least a modicum of financial security after years of earning poverty wages for teaching more students than full professors ever do, and you strike out…. It’s gonna hurt. Irony can be an immensely useful tool, but it’s never been a good shield. And the costs are too high, the costs of being stuck, of being neither in nor out.

I feel pretty much the exact same way about the state of writing as a profession. I’m mostly talking about journalism and takes writing, short-form informative/argumentative nonfiction of the type that has made up most of my career. People who write for newspapers and magazines and websites dedicated to politics, culture, and media, that world. I don’t think many people, within the profession or outside of it, would deny that its culture has become defined by an ever-deepening bitterness. Even writers who themselves Do Irony online all day will probably concede that the well has been poisoned; theatrical disdain for everything has become part of the furniture. It makes me genuinely sad when I see young writers gradually get socialized into the profession by demonstrating to their peers that they’ve given up hope. What a thing to inflict on young people. But since socialization into the hive is the single most important element of a successful writing career, they’re going to emulate what they see as the culture and values of the profession.

The only real communal activity writers take part in online is shitting on everything and affecting a pose as a knowing insider. This is a good example of Freddie Isn't Wrong.

But negativity and bitterness are not specifically what I’m talking about. Certainly many of history’s most celebrated writers have been possessed of a dark perspective on the world and its people. I myself am a pessimistic guy. What I mean instead is what I described in academia above, doing something but not doing it, committing in behavior but refusing to commit emotionally, treating your own career like a joke, disdaining the various trappings of success that you are ostensibly laboring toward in your chosen field, engaging on the subject of your craft only ironically, making sure people know you don’t take your own work seriously. I highly recommend against this common practice, especially for those young writers who are struggling to get established in a brutal market. Again, what’s the benefit? Hopping back and forth from one foot to the other, “I’m a writer”/“lol none of this matters to me” offers no protection against the pain of professional failure. It can’t possibly help you in your efforts to make it in the industry, and when you get older your attachment to appearing cool and jaded will instead look like the self-hating bitterness such behavior so often masks. If you’re planning to do this for the rest of your life, but you allow yourself no light at the end of the tunnel (whether financial or artistic) to strive for, who’s the joke really on?

This is what I’m saying about writing, and what I was saying about academia: you can and must always indict the fundamental injustice of the system, but if you choose to be in the system anyway, you should be in it fully, unironically, and without apology. The alternative is to do yourself a permanent injury. The only way to weather the layoffs and bad pay and union-busting is to believe that you’re doing this to satisfy a higher purpose. To deny yourself that as you tie your financial future to a broken industry is a form of masochism.

You don’t have to strut around like the caricature of Hemingway in Midnight in Paris. You don’t have to see yourself as some artiste who writes only by flashes of lightning. You can and should have a sense of humor about your work. But I don’t understand being in a craft profession and disdaining the craft, and I really don’t understand doing it for the money in a job with bad money. I also think there’s some self-hatred going on here where writing’s association with the literary and the artistic makes it seem less worthy of being taken seriously, as opposed to a (low-information and totally romanticized) vision of jobs where people “really make things.” I mean, would you really dismiss the craft of a woodworker? Mock one for taking it seriously, for being dedicated to improving it? I doubt it. Be as good to yourself as you are to your idealized vision of the salt of the earth.

Now, you might be the kind of person to say that it’s ridiculous to compare the craft of a woodworker to that of a writer, that the former is noble labor while the latter is intangible nonsense, the former creates things we need while the latter just moves words around, the world needs the former and not the latter, etc. Which, fine. But why on earth would you be a writer, if you don’t value the craft of writing? That word itself, craft, very often comes packaged with sneer quotes when people in this industry use it; the conceit, I guess, is that the concept is inherently pretentious. There are writers who feel that way. But I find it bizarre for someone to feel that way and want to remain a writer. You can make a lot more money, or at least more dependable money, elsewhere. Media is collapsing! Publishing is collapsing! The odds are just much better if you go get a job job. I had a bullshit office job for four years (before being fired due to incompetence) and it really wasn’t an awful way to live. Get the boring job, secure the bag, buy that house, raise those kids, and be happy. Nobody’s forcing you to be a writer.

If you do choose this, I think that's beautiful. But choose it.

All of this is just another facet of my old saw that there’s more ways to be a loser than a winner in our society. That basic impulse was the ultimate origin of my first book. (Which sold terribly, making me a loser in an additional domain.) Unemployed = loser, manual labor that’s not among the handful of jobs that are romanticized in our culture = loser, basic low-level white-collar job = loser, still trying to break into a creative field after your early 20s = loser…. I think a lot of people are really invested in finding a profession that still carries with it some cachet, a certain sense of desirability. Writing, as a profession, still has a little of that cachet left, battered though it may be. The endlessly-worsening professional conditions can’t quite kill it off, as the appeal of writing is ephemeral and fundamentally cultural. And I think “I’m gonna be a writer” is still a somewhat cool-ish thing to say when you’re in the immediate post-collegiate period of your life where you’re constantly asked to self-define. Nobody who grew up as an ambitious young striver with dreams of something deeper wants to tell people that they intend to get a good solid email job at State Farm.

Trouble is, those ephemeral benefits only accrue to you if you believe in them, and the fiscal landscape is as dicey as I’ve described in the past. If you’ve ironized the concept of caring about writing as something more meaningful than a paycheck, all you’re left with is perhaps a little bit of social juice on Twitter and in the rapidly-dissolving media social world in New York or DC. Perhaps you’ll even become the kind of writer other people ponderously congratulate when you get a new job as a staff writer somewhere making $55,000 a year. That seems like thin gruel to me, and it further seems to me that the impossible level of ambient bitterness in professional writing culture today is no coincidence. I genuinely don’t understand people who stay in the business and yet so theatrically disdain the idea that there’s a higher purpose to what we’re doing. How many waves of layoffs will it take before you just go get a boring-but-comfortable cubicle job? You can still be an asshole on Twitter, I promise.

Over the years I’ve mentioned several times that people in the profession, especially young people, will on occasion reach out to me, sometimes for advice, more often for commiseration. I think that when people become jaded about this gig, as so many eventually do, they want to talk about it with someone who they know to be an outsider within it, someone who’s been criticizing it for a decade and a half. I also think they trust me not to reveal that they’ve corresponded with me, and they’re right to do so. It happens that whenever I mention this kind of correspondence, media people have made fun of me for it - who would ever reach out to him?, they chortle. But writers do. They do because I take them seriously, and as is a precondition of taking others seriously, I take myself and my work seriously. You should try it. It’s free.