Anti-Racism is an Inter-White Struggle

intelligently fighting for Black quality of life means recognizing white incentives

In the 1990s a culture war broke out about rap. It didn’t last.

I turned 9 in 1990, so this period was part of my maturation into consciousness of a world outside of my home. It left an impression. There were many players: 2LiveCrew and Tipper Gore, Ice T and C. Delores Tucker, NWA and Frank Zappa. A new form of socially conservative respectability politics now cut across partisan lines, emboldened by incidents like Bill Clinton’s infamous “Sister Souljah moment,” leading to Congressional hearings about rap lyrics and a widespread perception that their portrayal of sex and violence in the Black community had gone too far. The Parents Music Resource Center, a cotillion of decent church-going women with mean, pinched, bitter, evil faces hoped to save the nation’s children from the filth pouring into their ears. On the other side stood those who argued that these songs merely revealed to white America the casual brutality and poverty which afflicted Black people, as well as an odd group of free-speech Avengers like Dee Snider and John Denver. It will not surprise you to learn that my sympathies were and are firmly on the side of those artists who fought for their right to free expression.

There is, however, another way to look at it: that this brouhaha demonstrated, among other things, that rap was a Black artform but a white obsession. The representations of Black poverty and crime were the authentic (and often brilliant) artistic expressions of Black artists, but they were financially successful and culturally influential because of the consumption habits of white teenagers. Rap could only become a white political fixation because it had become immensely popular among white kids. This is, I stress, not a critique of anything insincere within the music itself, but rather a function of white people’s dominant place in the population and the marketplace. Still, while the music’s quality was not undermined by the dynamic of Black artists growing up in poverty and reporting their experiences in music that was then lustily embraced by rebellious white suburbanites, the artform’s status as a language of rebellion must be. This is a tale as old as time - I mean, respect to Johnny Cash, but the man milked seven single nights spent in jail for every dollar they were worth - but it did demonstrate that, while art of all kinds has political resonances that have artistic value, there is no artistic language so confrontational it cannot be commodified. (Ahem.)

The political battle had real-world consequences; this was, in every sense that matters, a battle in favor of censorship. (Gen Z readers, it will surprise you to know that it was once the progressive and diverse side of our system that was opposed to restricting free expression.) But from an artistic and philosophical sense, and in the long run, I think the mass acceptance of this uniquely Black artform by white adolescents was far more challenging to rap’s advocates than Tipper Gore’s. Tipper made them seem like iconoclasts. Capitalism made them seem like merchants. And the fact that rap went from a punching bag for politicians to something they self-deprecatingly invoked, as documented in the video above, demonstrates that the critique of rap as a white plaything was correct. Rap was palatable enough to be assimilated.

In other words, the conservative attack on rap was the culture war rap’s defenders wanted to have. Being portrayed as dangerous and transgressive flattered the industry and its fans as outlaws and rebels. But the simple fact was that hip hop was a commodity, and like all commodities in this country it succeeded at mass scale only because it appealed to the white majority. Whatever the intentions of its creators, rap music was integrated seamlessly into the fabric of white self-identity - and ironically it seems that the uncompromising music of an NWA went down more smoothly than the conspicuously “conscious” work of acts like Arrested Development, which came and went very quickly. (Despite the brilliance of “Mr. Wendall.”) Dead Prez’s Let’s Get Free is a masterpiece, a work of absolute artistic defiance towards white tastes and white sensibilities, but we can be sure that more white people than Black have turned up the volume in their car to listen to “I’m An African.” That’s life in white America. To be Black in this country is to be literally surrounded and that must often feel suffocating.

I think this has been a regular cycle in these kinds of culture clashes. Conservatives play some voracious defense, then eventually the people who fund and control conservatism realize that what they’re fighting against doesn’t really threaten their stranglehold on money and power, and so gradually conservatives surrender - but while liberals can claim a victory, from the vantage point of history it’s not clear if they’ve won anything of substance at all. Rap’s ascendance to dominating sales charts and critic polls can be said to represent greater acceptance of Black culture, but it’s difficult to say what Black people got out of that bargain, aside from wealthy musicians. I suspect the critical race theory fight will go down in this way; liberals will succeed in getting CRT into many curricula, but people will come in time to realize that doing so simply doesn’t do anything. I mean, as I keep asking… why would it?

This is a recurring tendency, for Black cultural and intellectual rebellion to be folded seamlessly into an unbothered white power structure. Critical race theory, antiracism all of today’s self-consciously “radical” critiques of white supremacy and whiteness: they are all ostensibly Black discourses that are funded by white institutions and ultimately serve white people. I think the endless, pointless, going-nowhere fast debate about CRT shares this essential commonality with the earlier fight over rap lyrics and culture; both sides of the discourse have every political and professional incentive to represent a minor skirmish as a battle for the soul of civilization, and yet ultimately neither will produce much of tangible value at all. And in both cases the most salient observation is the fact that while what is being argued over is ostensibly Black cultural and intellectual production, the entire conversation exists to satisfy white desires and appetites. These are meant to be philosophies that liberate Black people from white frameworks, but the dynamics under which they operate reveal that their participants have failed to escape from the event horizon of elite white tastemakers, whose ominpresence in American letters ensures that nothing so black and brown can be made that cannot become, at its core, a white phenomenon.

Anti-racist discourse and politics in this country are not ultimately about people of color at all, but function primarily as a site of competition between different classes of white people. Black life has been instrumentalized by the very white people who are loudest about being allies to Black people. The “struggle” for white allies is, to a degree, a righteous fight to remove the immense burden of racist oppression from the backs of Black Americans. But it is inherently and without doubt also a struggle to position oneself in a place of moral superiority to other white people. It is a vehicle for inter-white competition, no more noble or enlightened than the status games white people play about the colleges they go to or the cars they drive.

I have previously mentioned this piece in the NYT about the unfortunate incident at Smith College, where behavior by a teenager that was mostly just thoughtless became something darker because of the way white leadership validated that thoughtlessness to avoid bad press. The somewhat callous (and, to be frank, privileged) behavior of a single Black adolescent who is no doubt better than that incident doesn’t concern me. The aspect that interests me is the conduct of Smith’s president, Kathleen McCartney. She strikes me as an archetypal educated progressive white person in the 21st century. McCartney engages with race under the guise of an authentic commitment to the moral effort against racial inequality, but all of her conduct suggests someone who is concerned primarily with stage-managing the reputation of her institution and herself. She acted self-defensively, punishing staff members without bothering to wait for the outcome of a perfunctory investigation she herself approved. When that investigation revealed facts that cut against the politically safe narrative she had dutifully peddled, she ignored them. She has spoken about the matter exclusively in bloodless progressive clichés that could have emerged from any corporate diversity training you please. It would certainly appear that President McCartney is more interested in avoiding Black censure than in improving Black lives.

But in fact her behavior is not fundamentally undertaken to please Black people at all. Rather it’s to make sure that the alumni, no doubt a dominantly white group, remain confident that the name “Smith” conveys the right picture in the minds of the other white elites against whom those alumni struggle for status. At a college like Smith, donations from alumni are a huge part of the financial picture. The school has a $2 billion endowment; you don’t get there with tuition checks. McCartney wasn’t really afraid of the Black response to this situation but rather of how the Black response might get reflected back by the alumni, the largely-white group that she actually cares about. Accusations of racism by a young Black student become the means through which an affluent white elite demonstrates her fealty to a largely-white group whose approval influences her future employment, the story of which is digested by a largely-white media and political class who use it to produce takes consumed by largely-white audiences, and at every step of the way white people take the opportunity to flex their superior anti-racism to other white people. You are entitled to think that what has come to be called “antiracism” represents the best way to wage the fight against racial inequality. But you cannot sensibly deny that, in the main, most of the antiracist discourse and activity undertaken in this country is refracted through white people’s endless competition against each other, and in so doing becomes something else than the liberatory movement it is sold as.

The great college-educated white people Olympics takes place every day, all over the country, in myriad ways. You are familiar with them. There are books written about them. The job you choose. The neighborhood where you live. Your inimitable, fashion-indifferent style. Your yoga app and your weekly trip to the farmers market, your loud love for Pose and Kendrick Lamar, your frequent (though now guardedly ironic) use of the word “bodega” - each signals status, above and beyond all other functions, at least to those with similar education and income. You’ve heard all of this from me before. What has evolved in the years that I’ve been talking about this stuff is the prominence of race in the competition. Anti-racism has become a kind of high-stakes poker game for educated white people: you risk losing your shirt at any time, but those who have the savvy and the guts to bluff their way to the top reap social and professional rewards. To be a white person who is identified as the right kind of white person, as an antiracist white person, is its own form of celebrity.

To put it simply, white engagement with racial justice efforts are inevitably an effort to establish professional, social, or political superiority to other white people. This is immutable and universal. These are not the exclusive motives of white racial justice efforts and can live beside more noble and authentic causes. But those darker, more primal, sublimated impulses are always rattling around in the psychology of a white person who wants you to know that they weep real tears over Black pain. Usually these motivations are self-defensive - I must appear to be against racism lest I be accused of racism myself - but often enough they are motivated by professional and social opportunism. In media, academia, and the nonprofit industrial complex, appearing to care more deeply about race than your peers is a path to riches and status. This is the world we’ve made.

For the record, this observation certainly applies to me and other left critics of CRT and associated flim-flam. I believe I critique current racial politics in the spirit of rescuing an authentic and effective movement to fight racism. But as a white person who is publicly opposed to racism, I am as guilty of being motivated by selfish instincts as anyone. The contrarian “ah but let’s peel the onion one layer deeper” style of race engagement that I take part in here is itself a kind of jockeying for position with the white martyrs for whom I have such contempt. (If anything, it’s an even more naked form, as my layering on of another level of arch criticism might result in deeper understanding of our race talk, maybe, but definitely makes me seem like a very clever guy.) This is a recurring feature of criticisms of white social signaling: while often accurate, they are usually also self-indicting, as calling out other white people for their status games is undoubtedly a status game itself.

Are our efforts against racism therefore permanently stuck in a hedge maze of white self-regard and self-interest? Does all this mean that white people can never be a part of the effort to end racism? No. Given that 70% of consistent American voters are white, and that white people have the money, it would be a declaration of surrender if the answer was yes. White people can contribute to making the world more or less racist; your choices as a white person matter. But all white engagement on issues of race has elements of self-interest and self-exoneration. I don’t think that’s disqualifying, if the point is to achieve certain tangible changes in the world through these efforts. If white people contribute meaningfully to improving Black infant mortality, who gives a fuck if doing so functions as a kind of grandstanding to their liberal white peers? The trouble is that today’s anti-racism has abandoned material change in the real, outside-our-heads world as the metric of interest. People in today’s discursive spaces talk vastly more about purging themselves of racially unclean thoughts and feelings than they do about reducing the Black-white wealth gap. DEI training isn’t designed to make the world less hostile to people of color but to make white people into more spiritually clean people. And so these universally mixed motives become more and more pronounced, more and more consequential.

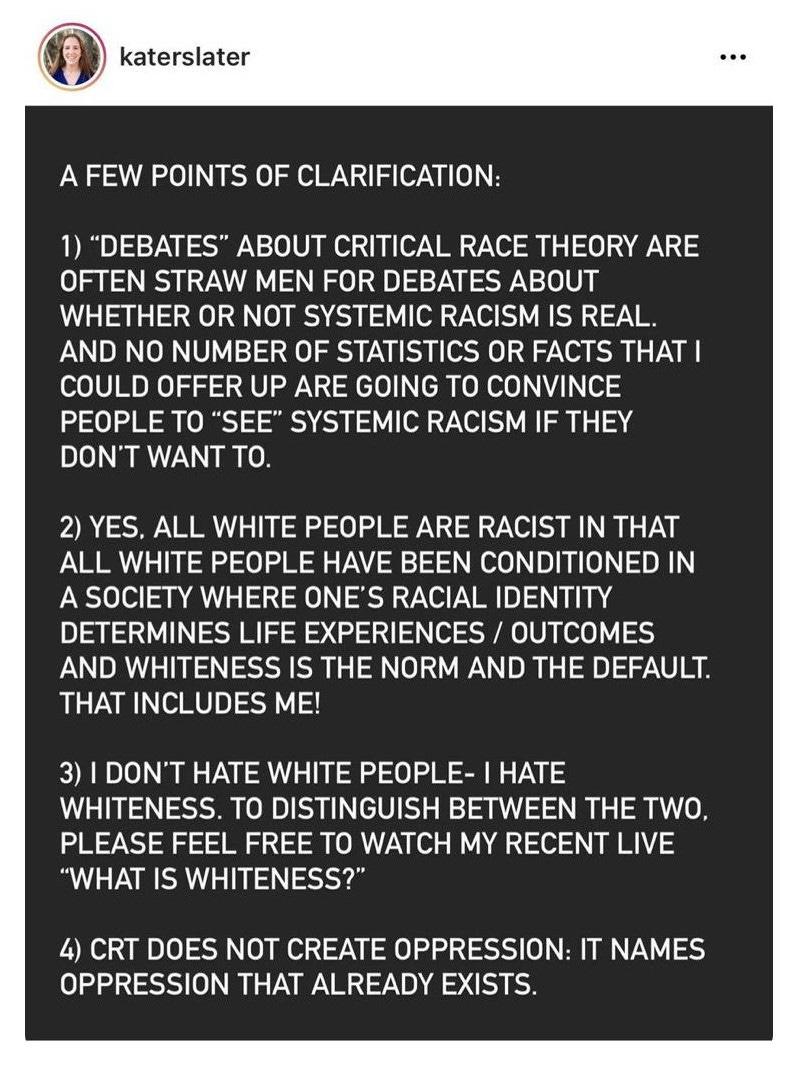

Here’s a good example of where we are in the “anti-racist” space.

Where to begin with this Assistant Dean at Brandeis?

Point one, particularly via its strategic use of scare quotes, effectively says that there is no legitimate criticism of CRT - which means that this white woman is, among other things, dictating to Black people like Adolph Reed and John McWhorter that they can’t have their own opinion on race politics.

“All white people are racist” is frequently thrown around (again, usually by white people) as a terribly radical and challenging position, but in fact it’s the exact opposite: when you generalize an accusation to that degree, it becomes toothless. There’s hundreds of millions of white people. If I share the condition of being racist with all of them, how can the claim seem specific, meaningful, and painful, to the point where it might prompt changes to my behavior? Specificity is the root of all effective criticism; as a writer I am immune to the distortions of people who misrepresent my work but exquisitely sensitive to those who faithfully repeat its arguments in the act of criticizing it. If you want to move someone by critiquing them you need to convince them that you’re engaging with their actual, specific behavior. Neutering the accusation of racist behavior in this way is the last thing we should want to do if we intend for the accusation to mean anything - but that’s the point, right? Inoculation represented as interrogation.

Abstracting “whiteness” away from what normal people mean by whiteness - the condition of being Caucasian as symbolized by pale skin and other phenotypical markers which indicate recent European heritage - can have only one function: to permit white people to consider themselves more or less white than their peers. After all, what is the political or social advantage of confronting whiteness rather than racism or even white supremacy? Individual acts of racism can be witnessed and denounced; the structures of society that undermine Black power and quality of life can be changed. But what does one do against whiteness? Nobody’s talking about white genocide except white racists, so what would political engagement with whiteness mean? It’s a completely inert way to understand race. And it permits precisely the kind of self-exculpatory behavior I’m talking about. I’m still connected with some (white) academics from my old field, and on Facebook they are forever complaining about other academics doing things more or less “whitely.” (I’m not kidding: “that was such a white lecture!,” complains tenured Irish-German professor.) Why? Because they can therefore think of themselves as the less-white white person. When you reduce “white” to a signifier-for-higher, a designation you can ascribe wherever convenient, you’re laying the ground for it to refer to other white people and not yourself. Critiques of whiteness derive their radical posture from the intrinsic and existential nature of racial categories, but this discourse just creates room for people to deny that very nature for the purpose of excusing themselves!

CRT does not create oppression, it’s true. CRT doesn’t do anything at all. Can anyone point to a single piece of evidence that CRT has ever had any positive material impact for any actually-existing Black person? Any evidence at all? By making it into a boogeyman, conservatives have done CRT and its well-paid salesforce the biggest favor possible: it has fixated the conversation on whether CRT is actively destructive, allowing the CRT industry (which is large, profitable, and growing) to dodge the question “what the fuck are we paying for?”

The overall point is this: by engaging in “the conversation about race” this way, this woman is not engaging in self-critique but the exact opposite. She is foreclosing on the possibility of genuine critical self-engagement through the adoption of a totalizing racial worldview that keeps her own behavior and culpability at arms length. It’s a remarkable trick. She earns praise for putting herself in a position of supposed vulnerability but in fact becomes impregnable. Anyone who criticizes my version of race politics is opposed to the fight against racism; everyone who is white is guilty of racism; but whiteness itself is an abstraction which I can reject and, in doing so, exempt my white self from the critique I so proudly perform; and anyway, surely I am not oppressing but “naming” oppression, which for some reason is the noblest endeavor a white person can undertake. Actually ending oppression, after all, would shut down the gravy train that enriches a few Black people but, more importantly, valorizes white people like me. This is a master at work, truly. This is life under the “deranged, neurotic mysticism” that you can now get fired for criticizing.

All of this is, of course, a rotten deal for the Black people who labor under racism. If I’m right, it means that the vast majority of potential allies have ulterior motives which, while they don’t undermine every benefit of what these allies do, do leave Black people’s interests subject to the whims of the affluent and educated white liberals who have hijacked antiracism for their own fickle self-interest. I’m sure it sounds insulting for me to say that anti-racism is primarily about white people when so many people of color are leading that effort themselves. But in a sense it’s just a numbers game: there are 250 million white people in this country and 42 million Black people, and the former are overrepresented and the latter underrepresented in the elite conversations where these topics are debated. When the numeric advantage is that stark, the center of gravity will always coalesce around white people’s interests. If “the conversation” is filled with white voices then it will break in favor of white interests. None of us can audit ourselves, no matter how sincere or passionate. We are self-exonerating creatures by nature.

Is there a way out of this bizarre identity cul de sac? Sure: forget motives and worry about effects. What’s actually working to help the average Black American in material terms? Not those that are fighting for TV hits, Oscars, or postdocs at elite universities, as much as we should want equity in those spaces, but the median Black person. This person, for the record, is not destitute as commonly portrayed but lower middle class and slowly climbing. They’re increasingly suburban. They have seen improving college education numbers in the past 20 years but slowing progress in the past 10. They saw record low unemployment in recent years but still were above the overall rate, with the post-Covid picture unclear. They have finally, in the past decade and a half, seen meaningful improvement in their odds of being imprisoned. But they remain far behind white America in most metrics. How is their life improving in this era of race relations? We have metrics to define this: the Black-white wealth and income gaps, the incarceration rate, life expectancy…. These figures represent a challenge for critical race theory’s proponents. Because it’s not just impossible to show that CRT has improved these numbers. It’s very difficult to explain how it ever possibly could.

There are all manner of things we could do to help the median Black American. To pick one, student loan forgiveness. Such a program would disproportionately help Black people, and the growing Black middle class especially. But to get student loans forgiven, we’d need to build a cross-racial coalition and minimize rather than emphasize racial messaging; as uncomfortable as this fact may be, the persistence of racism means that to fight racial inequality we will often have to downplay the racial elements of what we fight for. This cuts directly against the grain of CRT and similar theories, which privilege “centering” race far above actually achieving results that reduce material racism. And the emphasis on the economic dimensions of Black American life will always be threatening to those in academia and media who define race in purely emotive and linguistic terms - because it is in the world of emotion and language that they are powerful. But to consider these dynamics, I’m told, is to stand against the project of antiracism. What a shame.

What lesson should Black people take away from all this? I suppose there’s a few. “Don’t trust white people”? Maybe. But less crudely, “not everyone who says they’re your friend is your friend.” You would think that, after all of these centuries of oppression and neglect, pointing that out wouldn’t be controversial. And, above all else, to remember that every white person beating their chest about racial injustice is, one way or another, lining their own pockets. Including me. So you might as well focus on results, and who actually has a plausible argument about how we can get them. That might prompt an uncomfortable conversation, though. Because narrowing in on results in material terms could reveal the plain reality that it is the type of affluent urban college-educated white people who put BlackLivesMatter signs in every window who actually contribute most to the economy that marginalizes Black people, not the mythical Trump-voting laid-off Oxycontin-addicted iron workers. (Those people aren’t financially powerful enough to bend the economy, have zero influence in our cultural industries, and don’t vote. Remember, the people who put Trump in office were richer, not poorer, than the norm.) Putting the educated white liberal elite in the crosshairs poses particular challenges for the anti-racism industrial complex because those people make up the donor class that keeps the whole vast industry of racial indignation afloat. Ah, what a hall of mirrors, what an endless maze, what a sideshow. If only there was another way.

If your foundation for measuring the pace of racial equality is metrics like income, college education, etc. then the complicating factor is that it is not whites at the top of the heap in the United States but Asians. The entire CRT debate is really stuck in a world view where race relations in the US means the state of black-white relations rather than the reality of a multicultural society with a staggeringly diverse set of interests.

This post is pretty close to getting it. The instrumental value of CRT for corporations and schools is regimentation and policing. Of course it fulfills other needs such as moral pedagogy and religiosity. It serves an entrenched special interest: diversity administrators. Finally, it serves an institutional purpose as a kind of ‘insurance’ - CRT is a shakedown operation.

All of this is bad enough, but what is worse is that we don’t really know what the downstream effects will be. CRT is explicitly identitarian. It is also authoritarian in that it normalizes institutional involvement in what were previously private spaces. Finally, it is epistemically deranging. Critical theory in general is good at motivating action to get power (‘do your praxis’) but is bad at everything else. It leads to bad art, bad institutional governance, bad health policy, and the general dissolution of rigorous standards required in liberal discourse. What I think someone like Freddie, who is outside the institutions, misses is how cancerous the ascent of critical theory really is.