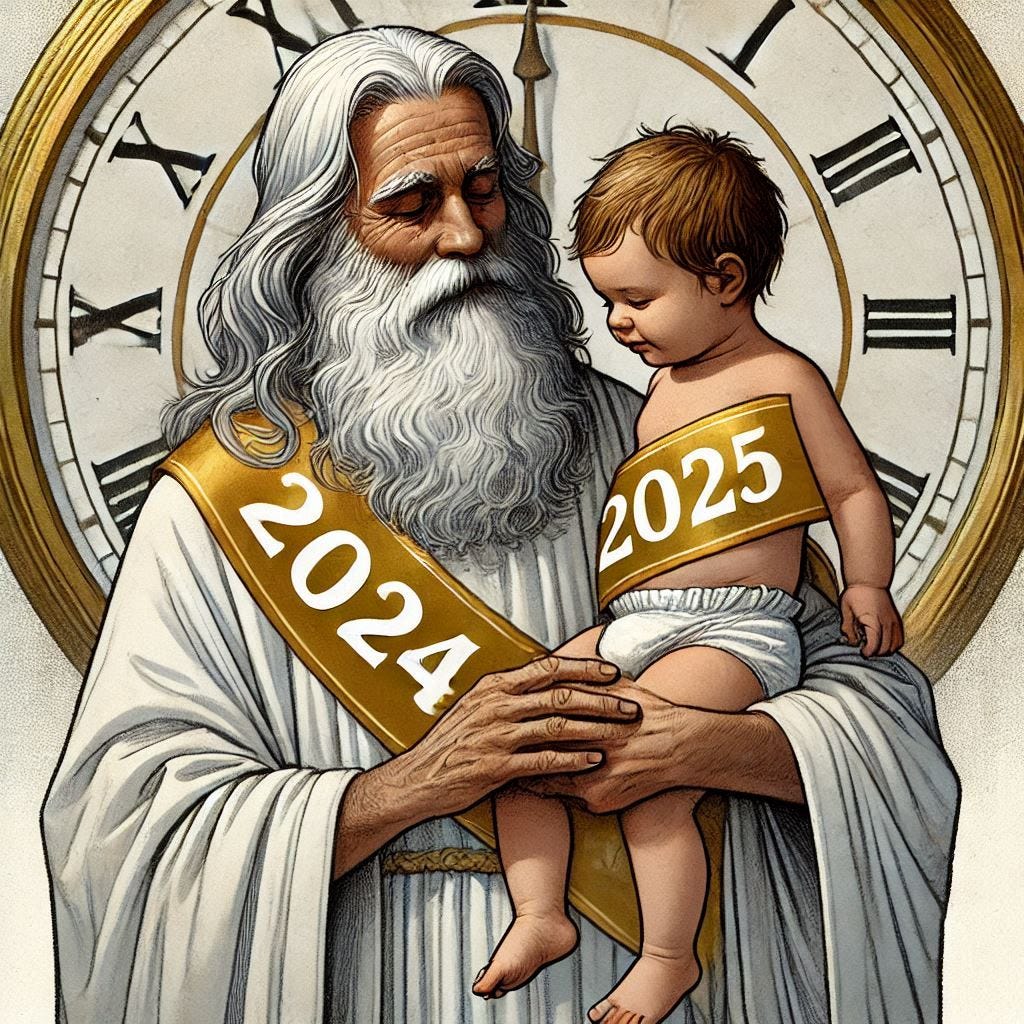

You know the score. Here are my superlatives for 2024, the things I loved, hated, or otherwise had strong feelings about in the past year. It was a big one for me; 2025 is going to be even bigger. I thank you again for your continued support, financial and otherwise; with a baby on the way, I’m more conscious than ever of what a privilege it is to do this. And if you want to help, please feel free to buy a gift subscription for someone who might like what I do.

Now on with the show.

Most Forced Meme: brat

To be very clear, this is not a comment on the album, as an album, but rather the meme - the endless media references to Charlie XCX’s album and the insistence that it represented some sort of cultural watershed, that The Kids adored XCX and this album and that it was some sort of cultural touchstone that united everyone, and particularly LGBTQ youth, in fractured times. People saying things were brat, then people saying things were brat but ironically, then people saying things were brat but reclaiming brat, taking brat back. New York running sixteen thousand pieces on the brat phenomenon; your aunt saying “brat” when asked for her name at Starbucks. Endless thinkpieces about how brat marked a new era of popular culture. It all was so mannered, so nervous, a little desperate. There was, indeed, a great deal of activity relating to brat. The trouble, from my perspective, was that this activity came from an older cohort that insisted that brat was what the youth were really into, in a way that always seemed transparently phony and disingenuous. It was youth stolen valor. Would brat as an obsession of the early middle aged have been sufficient? To me, yes. To our culture industry, no.

Again, this is something different from disliking the album or even the endless waves of meta-discourse about it. Yes, “Kamala is brat” was cringey and instantly exploded into a thousand dimensions of knowingness and winking, an MC Escher drawing of irony and performative droll detachment. That was lame. But that’s not what I’m talking about here. What I’m saying is that the brat phenomenon was an interest of the old that, for complicated and depressing sociological reasons, our cultural media insisted was an organic expression of the young. Here’s what I’m putting to you, without evidence: brat was never actually a big deal with the actual youth. Sure, they heard the songs, and when the album first came out they may have danced to some of the tunes. Plenty of them posted that annoying green square to their Instagram stories. But my individual, limited, and idiosyncratic experience has been that there was never a groundswell of interest in brat, as a phenomenon, among young people generally or queer young people specifically. I think if you talked to a bunch of the older Gen Alpha types they’d tell you that the whole thing seemed, indeed, to be a forced meme, an op.

So who was keeping this narrative going? Frankly, the brat phenomenon was the product of people in their 30s and 40s who work in arts and media, writers and YouTubers and podcasters who are unhealthily distressed about aging and who use their position as cultural arbiters to maintain their denial that their youths are now firmly behind them. This is, I think, a constant dynamic in artistic criticism and analysis in the mid-2020s, but because the people who might write pieces exposing that dynamic are the ones who are guilty of it, it goes unsaid. (Vulture ain’t publishing that piece, folks.) We’ve gotten to a place where the celebration of youth and disdain for the old has not just intensified but essentially left behind any residual intellectualized misgivings; a lot of people don’t even pretend to believe that there’s any value at all in aging or any superior virtues in the aged. Just as we’ve completely given way to worship of celebrity without any qualifications at all, at this point, we now don’t even bother to pretend that we think that there’s benefits to aging. We worship youth directly and shamelessly. And now the Millennials are arriving at middle age en masse and, surprise surprise!, we’re not taking it well. We’re really not taking it well, at all. We’re scratching and clawing to hold onto our self-identification as young people.

Now, I don’t think a 37-year-old is old. I think 37 is young. But because of this endless recursive deference to youth, the question you have to ask yourself is, when you were 22, did you think that 37 was old? The only honest answer to that question is yes. If you put youth on a pedestal, then you’ll have to accept youth’s definition of youth.

And, for various structural reasons, our professional media class is disproportionately made up of people in their mid-30s to mid-40s, with a median age somewhere around 38. I think this has a lot of consequences, but none is more pronounced than the tendency to use arts and media coverage - trend pieces, movie reviews, TV recaps, big-think essays on The Way We Listen to Music Now - as a way to negotiate one’s quiet desperation about getting older. This is exactly the case with poptimism; poptimists always talk and act as though poptimism is synonymous with the tastes of people of color, women, and the youth, that their ideological project is nothing less than to give a voice to the poor disenfranchised youth, sometimes youth of color, sometimes queer youth of color…. Which is all funny because, with apologies to people like Kelefa Sanneh or Ann Powers, the median poptimist is a white man, usually an aging white man. Guys like Sasha Frere-Jones, Carl Wilson, Rob Sheffield, Chris Richards, Jody Rosen, Jon Caramanica…. Each of these aging white men have built entire careers on what I’m describing here, the sweaty-palmed fear of appearing to not be with it, to be a Boomer, to be the middle-aged guy hanging out in his garage still listening to Pearl Jam. (Those guys express their love for music in a far more authentic way than the critics, for the record, and I hate Pearl Jam.) And then you have the white guy music writers who inevitably drift in the poptimist direction as they age, like Rob Harvilla or Tom Breihan of Stereogum, both of whom were interesting critics before they gave in to their fear of being a stereotype. There’s mountains of this shit from all manner of graying pasty dudes, and all of it to prove that they’re the cool aging white men who really get it.

Is it rude to insist that these guys have embraced their musical taste as a way to defy unflattering cultural assumptions about white men? I think it is, yes. But then, it’s the poptimists who really leaned into the idea that the new target of derision for cultural tastes, the white men still clutching their indie records, were doing so because of their unenlightened attitudes on race and gender. And it’s the kind of writers and podcasters who insisted that to not like brat was evidence of misogyny who have helped paint us into this corner. When I complain about the notorious Pitchfork album rescoring exercise, and point out that most of those rescorings say nothing at all about the music and only about how elite norms have changed around those albums, they tell me hey, music has always been about crafting a persona as well as appreciation. Well, here you go: the brat meme is a good example of how a lot of people, even many who have no interest in poptimism debates at all, try to stage manage their relationship towards culture in a way that makes them feel young, in a society in which we now nakedly celebrate youth and have no model of healthy aging.

I think queer youth are up to much cooler and less widely-publicized shit than whatever some ex-Buzzfeed staffer is talking about on Bluesky, I think that if I hear about any given cultural phenomenon, it can’t be underground or very cool, and I think brat became inescapable to some significant extent because a lot of aging writers thought that loudly associating themselves with it would make them seem young. That’s just my opinion.

I rest my case.