The uncharitable portrayals of medical personnel in this essay come from someone who has suffered in the system and has no place else to put those feelings but here. Forgive me for being unkind. But I have earned the right to say these things.

You have done your best to model what a person is and does for so long, playacting versions of yourself that seem like what others want to see like a freshman trying on personalities at college, and now you find that you chased this pleasant and false idea of who and what you are up a tree into the highest branches and can’t climb down. You would like to return to an authentic self but you wouldn’t recognize one if it tapped you on the shoulder. You have become lost in the performance of being OK, which you have played so diligently out of devotion to the people you can’t stand to see worry. You have spent the hours wondering if you’re crazy and the hours wondering if you’d prefer for the answer to be yes or no and the hours feeling guilty about that last bit. You have felt your self-control ebb and flood in a certain spastic rhythm that feels like constantly losing and then regaining your grasp on a bag of groceries that’s just a little too much to handle. You’ve watched as your paranoia congealed into something like a philosophy, a way of life; your conviction that your friends are conspiring against you now feels like a kind of lonesome integrity, a noble hill to die on. You are tired and you are coming undone and the question is whether you can grab hold of something before you sink into the marshy waters rising around you, or whether a part of you would actually prefer to finally taste their salt.

Maybe you still can save yourself. But you have to understand: the system does not want to help you save yourself. The system does not want you at all.

This is maybe not your first time. Usually your first time it sneaks up on you as quietly as a cat padding behind you on a carpeted floor and like a cat it pounces with both perfect focus and lazy indifference, reveals itself in a moment of unbearable emotional abundance, the world saturated like a picture from a bad camera phone, and suddenly you realize that you have been staggering around brain-drunk for a length of time you can’t quite figure. That party, a couple months ago, where they looked at you like you were weird - were you manic, or were you just you? So true undeniable evidence that you’ve lost your mind, when it arrives… it’s the grand reveal, the prestige. For me the memory is a slideshow - slowly losing my grip in my tiny studio in a shitty apartment complex called Hunter’s Crossing in my hometown, the transmission on my Ford Escort going out, taking a bath with all my clothes on, an argument with a neighbor in the parking lot, the light glaring pleasantly into my face through the window of a cop car, a shot of Haldol in my ass. To this day I don’t know what the legal process was that moved me from the ER to “the system.” I was sitting on a gurney, wondering why I had been left alone, feeling like I was tensing every muscle I had and some I didn’t, and the next thing I remember is someone putting my sneakers in a locker in a sad beige room.

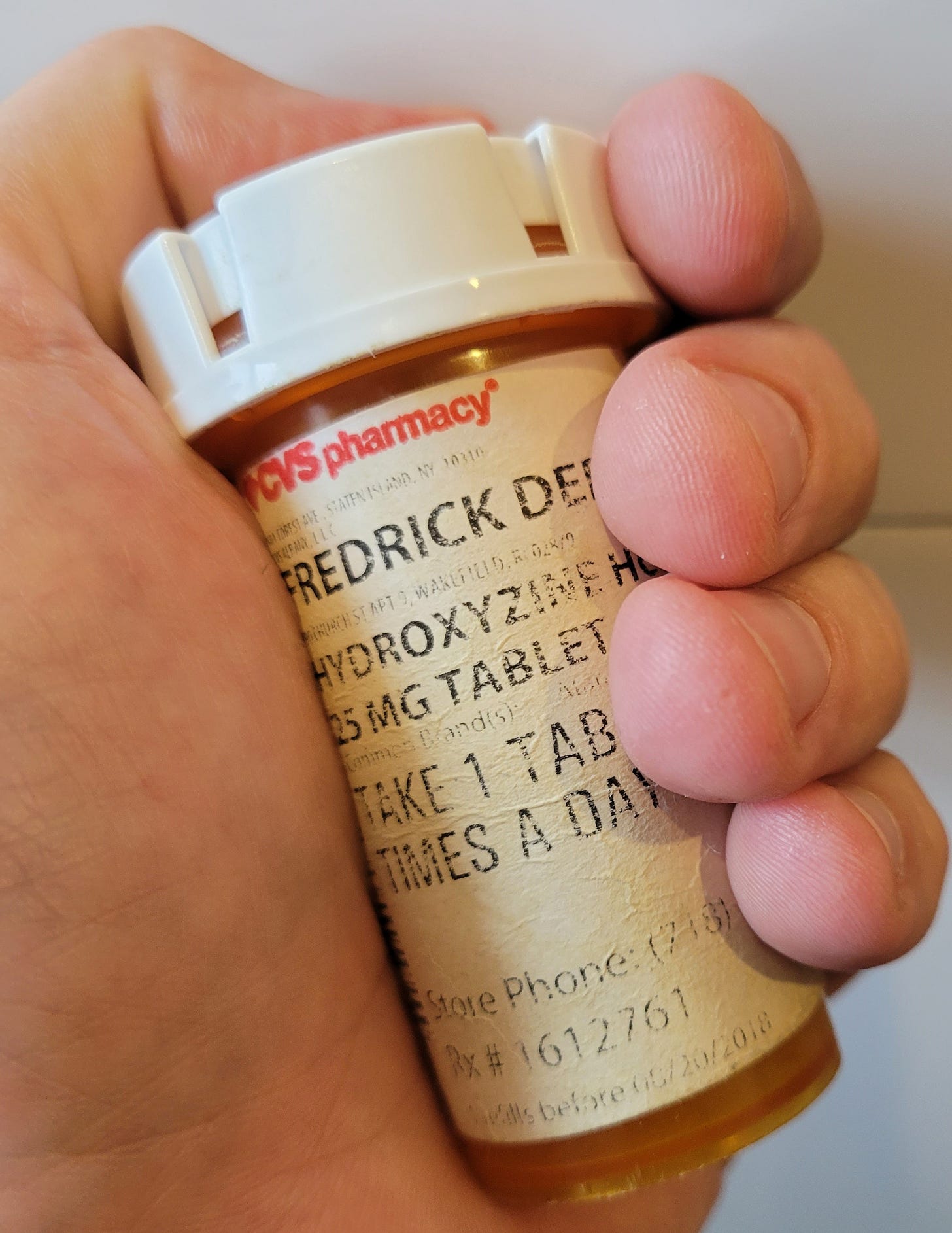

That’s the easy part, the incapacitated part. I would come to envy that former self in the years ahead, his fogginess, his pleasant blankness. The Zen Buddhists call it “beginner’s mind.” It gets harder, the more you know about the process, the less alien it all seems to be. Because in the following 15 years I ended up in one ER or the other seven times, if I recall correctly, a few times brought by friends, mostly by myself. Inevitably, I failed those friends and failed myself. I would hold orange pill bottles in my hands and stand in front of bathroom mirrors shirtless and see my rapidly softening figure and feel my foot shudder unbidden like an animal let loose in my own body and I would not take the pills. I stopped taking meds. Repeatedly. I made that choice and, eventually, I would accept the consequences. And the doctors and nurses and staffs at those ERs were mostly overworked and under-resourced, and the bored outpatient shrinks could write me scrips and order a follow-up but could not be expected to make me take the pills or find my way back to the office. I get that.

But they failed me, also. And when it’s your time, they’ll fail you too. The trouble is that as time goes on and you talk to more and more doctors and you argue over the phone with your insurance company and you get inured to group and the pills and the annoying fucking vocabulary, you get better at navigating it all - which means you get worse at getting help. Possessing that kind of experience can kill. Has killed. You don’t want to get good at talking to ER psychiatrists. So here is my guide for what to do when you come to the point where you can no longer stitch the frayed garment of your life back together.

You must prepare for the possibility that you will live the life of a detainee for some time. You will learn that this is, in fact, the happier outcome, and the harder one, and you’ll probably end up like Soapy trying to make it to the island, but that’s for later. I said detainee and not prisoner because prisoners of the criminal justice system have significantly more rights than you will if they decide to commit you. So if you go alone make sure someone knows which hospital you’re going to and tell them to expect a call, letting them know if you’ll be coming out or going in. Tell them to be patient; you will likely be waiting for a long time. Still it’s better to be delivered if you can be, but you will find that choosing who will do the delivering is a very fraught question at precisely the time when you are least equipped to answer such questions. There is a certain kind of friend who is both intimate and distant, whose compassion manifests itself as silence and who asks no questions besides “are you hungry?” and “do I need to take care of your cat?” The kind that looks into the maelstrom of your churning paranoid mania and sees in the heart of it the placid eye and addresses only that place out of friendship and worldliness. This is the best kind of person to bring you. Your mom is probably the very worst person to bring you. But it’s better than going alone.

Eat, beforehand, and pee too. Water your plants. Wear shoes without shoelaces and pants with no belt. Dress for comfort but be ready for them to take your clothes away. Jewelry, an expensive watch, your favorite headphones, those stay behind; things do walk away. Bring an ID and your insurance card - you must bring your insurance card - but empty your wallet of cash and credit cards, maybe keep a couple crumpled bills in your pocket for a snack or cab fare. (You will be going to a place where they will take your stuff from you and lock it away for a long time and you will already be imagining the staff performing all sorts of dark rituals to harm you and you don’t want to allow your brain to convince you that they’re using your Mastercard. Trust me.) Bring a phone charger, but don’t expect to have the chance to use it; if they check you in your phone will be sitting in a drawer or a locker for a long time before you see it again. If the nurses like you, you might see it sooner, but the nurses probably won’t learn your name. Grab a book. Grab two. You will have nothing but time. Print out a list of important phone numbers. I know what you’re thinking: you will not be in a position to remember such things, to remember anything at all, if it is well and truly time to go. But you can always put together a bugout bag for when the day arrives, and anyway, you’d be surprised.

Because psychosis is not a binary state. It’s rarely of the theatrical variety that you’ve seen in movies; people who have the privileges of basic stability and minimal access to care will hopefully get medicated before they reach the full bloom of totalizing delusion. Nor does even severe mania necessarily forestall the self-knowledge necessary to know that you’re in a very bad way. Yes, your brain wants you to believe that anyone telling you that you’re sick is out to get you, and yes, you think the way you see the world now is the deeper truth, the fallen veil, but your mind’s also perfectly willing to accommodate a quiet background understanding that you are deeply ill. After the first trip to the hospital and my one and only long-term commitment, I always knew that something was wrong, when I was descending. It’s not like the memory of sitting in a room while someone tells you that there’s something deeply askew within your brain is evacuated every time you go manic. These thoughts can live together - I have ascended to a higher state of being, and I badly need help - and the fight is to hold the latter long enough to forestall the total takeover of the former. The trouble is that, for one, there’s knowing things and knowing them, right? Plus, the way people talk to you in that state, the way well-meaning, loving people talk to you, the way experienced psychiatrists talk to you, the way ancillary medical staff talk to you, means everything.

So when you get it together to go to the hospital and put yourself in the immensely vulnerable position of admitting you need help, and they treat you like an inconvenience that they shouldn’t have to deal with, it twists the knife.

You will arrive at the ER, and your battle with the gatekeeper begins. The gatekeeper is called a triage nurse. There’s this movie A Flight of Dragons and in it there’s a monster called the Ogre of Gormley Keep and when I think of triage nurses I think of the ogre. They are a monster you have to slay if you want to get help. I know this is terribly mean and I know that it must be a truly punishing job and I’m sure that they are overstressed and overworked and I have tremendous sympathy for them, in the abstract. But I don’t live in the abstract. I live in my life. And in my life triage nurses have been a series of angry faces that don’t know why I’m sitting in front of them. They have only ever seen me as a distraction from their real job, which is helping people with real problems get help. See to them, people with real mental health crises show up in handcuffs or strapped to gurneys and they get pushed through past their desk. You, to them, are exaggerating, which means you’re weak, if you aren’t just faking it for attention. No, they’ve never told me any of those things. They’ve just looked down their noses at me from their computers while I’ve desperately tried to maintain minimal human composure and told them that I have nowhere else to go, and had them shove a clipboard in my face and made me wait, and wait, and wait….

This is the first thing to understand: they do not want you in their ER bed. None of them. Not doctors, not nurses, not orderlies. They don’t want you. They want gunshot wounds and broken ankles and strokes. You are a clog in their system, a wasted gurney, someone with a problem that can’t be fixed and isn’t worth taking seriously in the first place.

So the tactic is just to make you wait. You just wait. For hours. You get jumped in line time and again. I’ve sat for five hours before. There’s always someone who’s a higher priority than you, if you aren’t currently carving on your arm with a chef’s knife, someone who needs medicine in a deeper and more legitimate way. Making you wait keeps you out of their beds, is the main thing, but it’s also a strategy. Because they expect making you wait will result in two outcomes: either you’ll just give up and walk out, and you’re not their problem anymore, or that you’ll calm down sufficiently that when you talk to the doctor you’ll feel sheepish and ashamed and you’ll tell him that coming to the hospital was a mistake and really you just need a good night’s sleep…. In which case they can accurately report on their form that the patient refused care, and they’re not exposed to legal liability if you go home and hang yourself.

My most important advice is this: don’t calm down. Your panic and emotional devastation are your most valuable tools when you’re trying to get a cold and indifferent system to give a shit about you. The people in that system know, in some remote sense, that someone can appear relatively calm and be in deep need of psychiatric care. But when you’re trying to ring that care out of them in a busy ER on a Friday night? They see you looking minimally composed and think that all you need is a cup of tea and a good talking to. That’s why, when people contact me in the throes of a breakdown and ask to talk about going in - which happens more often than you'd think - and they ask me if they should take something, I always tell them no. No Xanax, no Benadryl, no glass of whiskey. Nothing that will artificially restrict the natural expression of your illness. Because it’s only that expression that can compel the lawsuit-avoidant edifice of emergency psychiatric medicine to care enough about you to get you into treatment. I am sure there are many well-meaning members of the medical establishment who would disagree. But I speak from experience. And you sit there and you sit there and you sit there and you wait to be called and your mind is insulting you the whole time, telling you that you’re weak, telling you that you’re being ridiculous, asking you to look around at all the people with real problems. It’s a gauntlet you run against the part of your mind that’s telling you that you don’t really have any problems and that it was a mistake to come. The part that’s a killer.

Of course, when you eventually do get past the triage nurse, there’s the doctor.

When it all went down in 2017, the last time I was unmedicated, my brother took me to RUMC because some hasty Googling had revealed they would probably take my insurance. But they also have a separate psych ER, which meant there is no triage nurse, or there wasn’t for me that day, anyway, none that I recall. My brother talked to somebody when we walked in and I was shown right through. I saw the doctor faster than I had since I was brought in by the cops. Which was nice. But then it was time to wrestle with the doc.

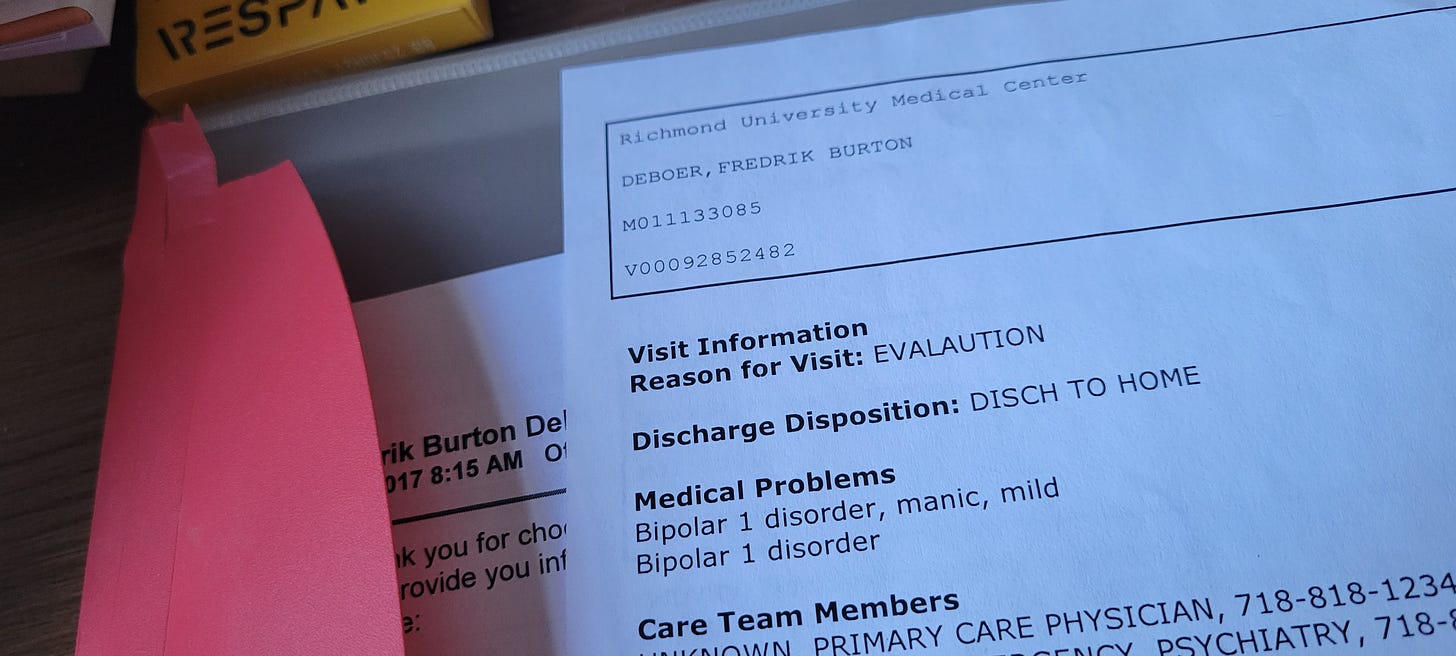

Please consider the image at the top. It looks like a happy story; my case was mild, I was discharged to home. But that slip of paper, an appointment with a social worker, a bottle of Vistaril - these were all the fruits of an hour-long battle with a skilled combatant. You see where the indifference of the triage nurse is cold and dismissive, the indifference of the ER psychiatrist is patrician, condescending, distant. The ER shrink is concerned about you the way your guidance counselor in high school was - not mad, just disappointed, friendly and judgmental and superior and vague. At RUMC he was nice enough, as distracted as all of them are, seemingly very competent, and openly bored. When he took my history he asked about my first manic episode. I told him the story and he said, I swear to God, “that’s it?” I stammered for a bit, but yes, “that’s it” - I got into a screaming argument with a neighbor who found me frantically trying to push my car into a parking space, and another neighbor called the cops, and they took me to the hospital. I almost apologized to him that my first psychotic break wasn’t more cinematic. It was immediately clear that my problems were not going to be sufficiently dramatic to him for me to receive real care.

You have to understand, again, people's manic brains don't work in a way that would make recognition and diagnosis and treatment easier. I'm sorry to say. For months I held down a job and paid bills and did other normal person things, while I simultaneously believed (for example) that the hosts of a popular podcast were using Reddit to conspire against me. The doctor at RUMC could easily set aside the darker symptoms since I could communicate and had showered in the previous week. In this he was like most ER docs I’ve encountered, and it’s here that you must strategize.

The deck is stacked against you. Like I said, when you get in to see the shrink you’ve usually been sitting and feeling like a overreacting piece of shit for hours. Which means you’ve been convincing yourself that you’re doing something terribly embarrassing, and so when the doctor graces you with his presence you fail to make eye contact for the ten minutes that it takes to apologize to him for being there and then maybe he gives you three days worth of Ambien and you’re gone. (I apologize for the gendered language. It’s just that every ER shrink I have ever interacted with has been a man.)

They want you out of their ER. What you’re saying does not impress them. You need help, but you aren’t chewing the furniture, so they’d like for you to hit the street please. You’re presented with the question: do I say the magic words?

The magic words, of course, are some version of “I believe I am a danger to myself and to others.” It’s a conversation starter; you can get the most bored attending psychiatrist’s attention that way. If you say such things and they let you go and you stab somebody, they can get sued, which the obviously don’t want - And the law gives them the tools to prevent that. In most places in the country, that kind of talk can get you involuntarily committed. Here in New York it’s a 9.27. In California it’s a 5150. I studied up on these things one long weekend in like 2010, snorting Ritalin, writing a lawsuit about a recent trip to a Providence hospital I found unsatisfactory. What everybody says is that, while there’s all kinds of state standards and laws and statutes, if the system wants you it can have you and it can keep you. If the doctors think you need to go in, you will go in, and no judge will stop them, and if the doctors think you need to stay in, you will stay, and no judge will get you out. Jailhouses at least have jailhouse lawyers. You get stuck up in the right mental hospital and don’t have the money to get a lawyer to really fight for you? You’ll stay as long as they please. People talk about 72 hour holds, but they can just keep stacking those, one on top of the other. In practice if not on paper.

Involuntary commitment is a life ruiner. You have no idea when you’ll come out. Got a dog? Hope your neighbor can take him, or you can absorb a $5,000 kennel bill. Got a job? Hope your boss likes you; theoretically the ADA protects your employment, realistically you’ll find out you were fired weeks after the fact and you probably don’t have the money or the psychic resources to successfully sue. Got rent to pay? Got relationships to maintain? It’s all backburnered. Hope you never run for office. Hope you never get into a custody battle. The time off and the isolation is the point, right, except that if you didn’t prepare for that then it can ruin you, and you didn’t prepare for it if you got 9.27d, did you? But it turns out that there are times when the refusal to pay attention to you - not just the nurses and the doctors and the system but your whole life and everyone in it, your boss and your boyfriend and your parents and your friends, their annoyance with all of your needs - feels bigger than all of that. The need to see what’s happening inside of you accounted for, sometimes, is the most powerful motivator in your life. So magic words are a card you can play, a big one. Sometimes the question is, are you offended enough by the boredom and the indifference of the nurses and the doctors to play it? Do you force the attention they won’t give you willingly? I’ve never been able to force myself to do it. The cost to autonomy is too high. And so is the insult to pride.

That’s what happened at RUMC. I wanted to get inpatient help, and I wanted to be taken seriously, but I didn’t want to be involuntarily committed. It’s a delicate operation and I’ve never pulled it off successfully. I think too much (the weight of experience again) and I play it too light or too heavy. I told the guy the truth - that I feared that I was being pursued by the railroad police, a constant theme of my manias since I saw the movie Into the Wild, and that I had accused an ex-girlfriend I hadn’t seen in a half-decade of hacking into my bank account. But I also didn’t want to get involuntarily committed. I had a job and a dog, and I had a great desire not to have to eat sugar-free Jell-O while I watched Jeopardy! in the common room for a month. But there was another layer, and I suspect that this is what will seem the hardest for people to comprehend: I wanted to preserve whatever dignity I had left. Again, people think, OK, bipolar mania, intense paranoia, delusional thinking - how was he in any position to think about dignity at all? But it’s not a light switch. You don’t suddenly abandon your attachment to appearing to be a self-sufficient, functioning adult who deserves respect. If anything you cling to it all the tighter as you circle the drain. So I was left in a position I have been in over and over again: a doctor who I’m sure meant well but who didn’t see me as someone who looked the way the typical New York City mental patient looks, an administrator who was thinking about keeping beds clear.

I am sure that almost all of the nurses and doctors who have treated me have, in their hearts, a deep dedication to healing. (Not Dr. L******** in Indianapolis, though, he can go fuck himself.) But the incentives are all fucked up, between malpractice and liability concerns, the absolute horror show of American health insurance, the entrenched inefficiency of overworked and underused hospitals based on geography and class lines, the casual invocation of involuntary commitment in some places, the inadequacy of resources for mental health in almost all locales, the professional imperative for talented doctors to get out of hospitals and into lucrative private practices pushing Lexapro and Vyvanse…. It’s not a healthy system, and while I know many doctors agree in general, few of them probably agree with me on specifics. Reform seems unlikely.

There are other concerns. When the doctor asks you about drugs and alcohol, what do you say? If you’re sure that those aren’t the real problem, you may want to say that you never do drugs and you barely drink. “Couple drinks, couple times a month, with friends from work, that’s it,” might be what you say if you drink a bottle of wine a night. Chalking up your problems to substance abuse makes things nice and comprehensible for the people diagnosing you and there’s programs they can sign you up for and the next thing you know it’s six weeks later and you’re sitting in an AA meeting while your untreated schizoaffective disorder rages inside of you. I’m not saying that I know better than the doctors, or that you will. I am saying that you need to make sure that you don’t get checklisted as an addict if that’s not your real problem. Of course, that probably is one of your real problems, and sometimes people go to get treated for mental illness to avoid confronting their addictions. All I’m saying is, the system has avenues it wants to push you down, canals. And if you give them what they need to send you down the drugs-and-alcohol path, you’ll find it that much harder to figure out what’s really wrong, if something else is really wrong. So make sure they know there’s other problems. Comorbid, they call it. There’s no shame if rehab is what you really need. Obviously. My daddy was a pig in space.

Insurance will fuck you. They’ll find a way. The facilities you go to often won’t be in-network or out-of-network, in some uncomplicated way. That would be too easy. The individual doctors you work with will be or won’t, or your meds will be covered but not therapy, or your group will be covered but one-on-ones won’t be…. There’s nothing you can do, at the outset. If you try to sort that all out before you go you’ll never go. All you can do is hope for the best and hate the American medical system with your whole heart until the day comes that we replace it with something minimally humane. For the record your insurance will tell you the same thing that some people will say in response to this essay: outpatient care is the appropriate place for you. Emergency care is only for the raving people, the ones who climb onto the subway tracks, the ones who shit their pants. Your life is falling apart and you see dark forces gathering against you around every corner and you’ve counted your teeth with your tongue until the tip is raw and bleeding, but what you need is outpatient care. You know. The famously easy and cheap process of seeing a specialist in the American medical system.

Here’s what I know. People with punishing mental illnesses have finally gotten it together to seek help, driven to the very brink, to the limits of their composure. And they’ve shown up at hospitals and been greeted by disdainful staff that force them to wait for hours and greet their pain with indifference and, often enough, disdain. They’ve been told, one way or another, that they shouldn’t have come. So they’ve left, and they’ve tried to go back about their lives, but their disorders pulsed on, and some of them have ruined friendships and marriages, and some of them have committed crimes and gone to jail, and some have physically harmed other people, and some have poured a warm bath and slit their wrists, all because the emergency medical system seems to think that if you don’t present with operatic madness like out of a Batman cartoon, your problems don’t rate, aren’t real. And sometimes I think about that, and I think about all the times I tried to get help and got only condescension, and then ended up getting “help” the hard way a month later, and it chews me up inside until I force the thought away.

That “discharged to home,” in the paperwork at the top - that was actually “discharged to a street corner in Staten Island, utterly directionless and afraid, with a brother who didn’t know what to do any better than I did.” And that “mild” is the mark of someone making sure no one could accuse him of discharging someone who was out of control. “Mild” after I had driven a close writer friend and comrade to the point of cutting me entirely out of their life, after I had made so many theatrical demands for loyalty to the point that it became cyberstalking and harassment. “Mild” after someone else I had once been very close to had threatened to call the cops, doing me the favor of finally driving me into this latest attempt to seek immediate help. “Mild” after I had just harmed a completely innocent person based on a bizarre and evidence-free belief that he had put my name on a hit list and in so doing subjected him to grief he did nothing to deserve and ended any ability for me to ever get a regular job again. To that doctor all mild really meant was “somebody else’s problem.”

I hope you have money. I hope you have partner or activist parents who are used to getting what they want. It would make everything so much easier.

After the beginning of treatment comes the digging out. And the first part of digging out is simply remembering the things you had done, now in the cold and antiseptic light of day, like the light of a surgeon’s table, when there’s no more pleasant delusion to help you lie to yourself about what you have done. It’s a unique experience, in a sense sublime, when you look back at months of behavior and a dam that had been holding back the rising waters of self-knowledge suddenly bursts and all you can do is realize that every person you fought with for weeks and weeks was right all along. Eventually you must forgive yourself. But it will take a long time. A very long time.

I wish I could take every one of you that needs it to the hospital myself. It wouldn’t be my first time, on the other side. Here is what I have to say to you: the options are negotiated surrender or unconditional defeat. You can’t play out the clock. You know if you’re suffering. And if you’re suffering, what are you waiting for? Why delay when it will only get worse? For me it feels like someone gradually chipping away at my mind, achingly slow, one grain of sand at a time. So from day to day I don’t much notice what’s newly gone, and that’s how you wake up one day and your arms are covered in unidentifiable scabs. Why not go now?

Perhaps your resistance is political. It’s a trendy issue in the left-right nexus, the idea that we’re overtreated for psychological problems. From the I-read-too-much-Lasch “right” to the trust fund granola “left,” everybody is sure that it’s all a conspiracy from Big Pharma. Fucking deep, man. Well, maybe “we” are overtreated. But you are not. You are suffering. And part of your suffering is that you’re trapped between the social expectation to be alright and the social expectation to model being not alright in an Instagram-friendly way. The choices appear to be soldiering on with some parody of Irish reticence or whoring out the worst parts of yourself for cheap “engagement.” But what you will find is that when you’re sitting in some hospital’s observation room, waiting for someone to come spend 5 minutes with you before deciding if it’s to be the kind of state facility you don’t want to end up in or the street, is that this viral debate about psychiatric health, the Mad in America bullshit about what being sane really means, is just totally remote from anything that matters to you. If there was ever any doubt, you will come to know that the trendy announcing-my-disorders-on-Tik Tok vision of mental illness has no actual bearing on the day-to-day work of living with a disordered brain. It’s not sexy and it’s not fun and it’s not something you want to define you. It doesn’t feel like a courageous battle with cancer. It feels like everyone knowing you have venereal disease. If you wind up committed you won’t spend your days pondering “who’s really locked up in here, us or the doctors?” with Chief Bromden. You’ll spend your days hogging a communal toilet because the lithium is doing a number on your GI tract and all of the other patients will know how many hours a day you spend shitting. It’s not ennobling. It’s pathetic.

But that’s the beauty of the path I’m saying you are allowed to take. Because there are no optics calculations when you really hit rock bottom. That is the one silver lining, if you can call it that, in a part of life that Hollywood loves to pretend is profound but is actually only devastating: when you really and truly go, you will feel unseen in a way you have secretly desired for years and years. So collapse, with me. Collapse into the death of pretense. Collapse into not caring. Collapse into the numb blessings of clozapine and Ativan. You get what most people never get, which is to give up, to say the two most beautiful words in the English language: I surrender.

It gets harder, after. Pills are hard. Therapy is hard, if you can get it. Wrestling with insurance is hard. Going back to work is hard. The way your friends never look at you the same is hard. But for now, all you have to worry about is whether you are ready to collapse… and whether the system will allow you to.

My brother took me home after Staten Island, that day. It was a lot of work to get me long-term care. After some anguished calls for help in my personal network I was hooked up with a doctor who would see me once, off the books. He gave me a shot of Geodon, the second of my life, so that I would stabilize sufficiently to be able to seek permanent help. He acted like it was all very hush hush, like he was pulling off a heist, and I felt like a drug kingpin going to see a plastic surgeon in secret. “I’m not diagnosing you,” he said as he jabbed me in the shoulder, “but I can’t believe you’re walking around like this.” I would return to RUMC for the social worker’s appointment, but when I told them that I could not return to Staten Island every time I needed to see a psychiatrist, they told me they couldn’t help me and sent me away. Somebody else’s problem. Eventually my friend Katie Halper helped me get a permanent prescribing psychiatrist, who I still see.

When I went to his quiet little office by the East River for the first time, we sat and talked for a long while. He had decades of experience, a sharp clinical mind, and charged me far less than a successful Manhattan doctor ordinarily would. More importantly he was gentle and kind. Nothing I said about my history surprised him; it seemed to be, in a comforting way, exactly what he had been expecting. He did me the favor of not sugarcoating the hard part: it was back to meds, to high dose lithium, probably Lamictal, definitely antidepressants, and when I told him I could not tolerate Seroquel, to olanzapine, an antipsychotic, the drugs I have spent my adult life running away from. I told him I had been having mixed feelings about the Geodon shot, and was dreading the olanzapine, though I had known it was coming. I babbled about how it didn’t seem fair, to be back on antipsychotics, and vaguely suggested I might not need them. You would be surprised, the urge to play lawyer for your manic self.

“Well,” he said, not unkindly, “you’ve been psychotic.”

When he said it, I cried.