The Rage of the AI Guy

I'm only asking you to observe the world around you

The ChatGPT/LLM era is now old enough that the discourse cycle has gone round quite a few times, which means we now find ourselves in the metadiscursive phase, when half of the discourse is about the discourse. Since we’re mostly all sitting around waiting for the AI rapture to arrive, it’s little surprise that things have gotten a bit… decadent.

Consider this post by Scott Alexander of Astral Codex Ten. His piece isn’t about AI but rather recent developments in using IVF to select for embryos with desirable traits, which is now a field with several prominent for-profit competitors, a good deal of investment, and a growing customer base. This isn’t actual embryo editing but rather embryo screening, which that can have a larger effect than you’d think. (This kind of thing might prove to be a big deal.) The piece is Alexander at his best, a demonstration of why he’s been so successful as a writer: it’s deeply knowledgeable, patient, thorough, willing to wade into some fairly deep technical waters, curious, and skeptical where warranted. He sees the potential for the technology but is aware of the challenges. He considers various ethical and political dimensions in a way that’s engaged without getting dragged down into the morass of those controversies. I came away from the piece better informed and entertained.

And then, near the end, he says “The average age at diagnosis for Type II diabetes is 45 years. Will there still be people growing gradually older and getting Type II diabetes and taking insulin injections in 2070? If not, what are we even doing here?” That’s right folks: AI is coming so there’s no point in developing new medical technology. In less than a half-century, we may very well no longer be growing old. Pack it up! Any resemblance between this promise to end aging and many millennia of witch doctors and conmen claiming to do the same thing is purely coincidental.

What I want to underline here is not the overconfidence in our near “AI” future, not yet. For now I just want to call your attention to the incredible disparity in evidence and analysis when comparing the rest of the piece to this tossed-off supposition that human life will be fundamentally changed within the author’s lifetime, in a way that might spare him from the great fear that has haunted humans since we became sentient. (That is to say, the fear of death.) Just consider the wide gulf between the analytical tools he brings to bear on the topic at hand and his breezy hand-waving insistence that AI is going to obsolete the entire field of medicine. I am just fascinated by this, by both that juxtaposition and Alexander’s seeming failure to parse it, his apparent lack of understanding that he’s just stepped from an admirable standard of rigor and precision to engaging in an unjustifiable fantasy. And I’m profoundly dismayed at how this kind of abandonment of even the most minimal evidentiary standards has become normalized in a few short years. Something is genuinely lost when a guy like Alexander can fall into this rank irrationalism without realizing he’s done it.

No one could have avoided hearing the loud, repeated, increasingly shrill insistence that we stand at the precipice of a great revolution in every aspect of human life, thanks to “artificial intelligence,” which here refers to large language models that return strings which are deemed algorithmically likely to satisfy written prompts. Alexander, for his part, insists that AI is “not ordinary technology.” The AI era we’re supposedly living in has generated the most profound hype cycle in American media, arguably, since the post-9/11 terrorism freakout. And yet there’s a bizarre refusal to accept that the maximalist position has won the news cycle.

The stodgiest publications constantly shovel out the most overheated AI hype; arguments that AI will literally exterminate the human species or bring about utopia are a dime a dozen. Everyone is straining to cram the words “artificial intelligence” onto every pitch deck, resume, and product description they possibly can. The New York Times, which will fact check the statement that the sky is blue, runs a special issue of its magazine dedicated to AI in which not a single line of real skepticism appears and are now running straight-up AI fanfic. Absurd AI companies and products abound; it’s not just boondoggles like the Humane AI pin but things like AI binoculars, dog bowls, and toothbrushes. Scandals like that of Builder.ai - which should have their own code word, IAJI (It’s Actually Just Indians) - become more and more common, and yet every other day some big thinky piece titled “Are We Actually Under Hyping AI???” gets published to a lot of chin scratching. It’s a weird time.

Attending it all is this conspicuous anger. Alexander has taken a few weird swipes at me in the past year thanks to my gentle suggestion that perhaps the impulse to believe that we live in the most important time in human history is one to distrust; he appears to be growing impatient with disagreement in this space in general. Still, he’s far more composed than the armies of rabid AI fans online who sit around on Reddit muttering darkly about the imminent AI rupture that, they believe, will devastate the people they don’t like and enrich themselves. This general belief, that we live on the edge of the great fissure in human history that will sweep away all of the terrible mundane burdens we live under, is a relentlessly repetitive one in the story of our species; millenarianism is an constant in human life, across eras and social systems. Of course, many respond to this observation by suggesting that, where every other human being to predict the end times has been wrong, they are right, because they are smarter than everyone else who has come before - which of course is also what everyone else who has come before thought too.

I will not relent: this period of AI hype is built on twin pillars, one, a broad and deep contemporary dissatisfaction with modern life, and two, the natural human tendency to assume that we live in the most important time possible because we are in it. Our ongoing inability to define communally-shared visions of lives that are ordinary but noble and valuable has left us terribly frustrated with the modern world, and our sclerotic systems convince us that gradual positive change is impossible. Hence pillar one. And the very fact that we have a consciousness system, the reality of our lives as egos, of dasein, makes it very difficult to avoid thinking that we live in a special place and special time. Hence the second pillar. I’m not assessing character here; the solipsism of consciousness is inherent, and our nervous systems are set up to make us feel that we are the protagonists of reality. I too have to remind myself that I don’t live in a privileged time. But I think adults do need to fight the temptation to think that way, and unfortunately the limitless sci-fi imaginings that artificial intelligence invites has made this habit irresistible to many.

Take, for example, this piece by Yascha Mounk, an even better example of a generally even-keeled guy who’s apparently had his brain broken by AI hype. It amounts to a series of assertions where Mounk’s certitude and frustration are taken to be proof of what’s being asserted, which is common with this topic. For me, the post underlines the fact that the desperate hunger for deliverance through AI is fundamentally emotional, not intellectual. Reading the piece feels like watching Mounk pace around in the cell that is human existence, muttering to himself, working himself into a lather, growing more and more bitter that anyone has suggested that perhaps tomorrow will be more or less like today. Which is, for the record, easily the best bet that any human being can ever make.

Mounk is very angry at Jia Tolentino for saying in an essay that she doesn’t like contemporary LLMs, doesn’t find them useful or trust their social effects, and so doesn’t use them. That is really it; that’s the source of Mounk’s anger, the indifference of people like Tolentino (and me) to the LLM “revolution.” Now, I suspect the quiet part here is that Mounk himself probably now does very little of his own writing, farming most of it out to LLMs, and feels judged by the fact that Tolentino (like myself) does not use LLMs in her own work. [Update: Mounk has taken considerable umbrage to this sentence, in fact calling it libelous. While I continue to believe that it’s a perfectly natural supposition given his own stated feelings in the piece in question, I certainly believe him when he says that he does not use LLMs in his writing in this way. Please integrate that into your understanding here.] This defensiveness has become very common too, so it’s not a particular swipe at Mounk; a lot of people who call themselves writers appear to spend most of their days talking themselves into believing that having ChatGPT do their work is still “really writing.” But the broader thing with Mounk’s essay, I think, is the same simmering resentment that has filled so much of Alexander’s recent output and which haunts the whole topic. Let’s take a look.

“The history of the world will be split into a pre‑AI and a post‑AI era”

Spare me. Every decade some pundit declares a synthetic apocalypse or utopia. Calling AI epoch‑making feels like marketing copy for venture capitalists crowing about “disruption.” Yes, there will be significant changes to human life thanks to the gradual and piecemeal development of machines that approximate certain elements of human thinking, but there will also be equally or more meaningful changes wrought by climate change, gene editing, extreme weather, global debt crises…. The Christians say that the world is divided into the time before Jesus’s sacrifice and the time after, the time of the Second Covenant. The Muslims believe al-Mahdi will come and his coming will be the transition from before to after, that he will usher in the day of judgment. The Maori of New Zealand had the concept of Pai Mārire, the coming of the archangel Gabriel to purge the land of corrupting European influence. A teenaged Xhosa girl told her community that slaughtering their cows would bring about rebirth and chase off the British, and she was so convincing she sparked a famine. The Jacobins believed that smashing the ancien régime would not lead to another, better but conventional government but rather to The Republic, a quasi-mystical future governed by virtue and reason. I could go on, and on and on. Eschatology is a constant of human social practice, and very often the people practicing it don’t believe they’re practicing it at all.

Anyway. Mounk catalogs three flavors of supposed denial: that AI is incompetent, that AI is just a stochastic parrot, and that AI’s economic impact is overstated. None of these accurately expresses what many AI skeptics are saying, and each is ultimately answered the same way AI maximalists answer everything: by asserting that some future projection simply will occur.

Mounk mocks the idea that AI is incompetent, noting that modern models can translate, diagnose, teach, write poetry, code, etc. For one thing, almost no one is arguing total LLM incompetence; there are some neat tricks that they can consistently pull off. The trouble is that these tricks are mostly just that, tricks, interesting and impressive moves that fall short of the massive changes the biggest firms in Silicon Valley are promising. And the bigger issue is error detection or correction: ChatGPT will very often return interesting and more-or-less factual outputs, but it will also often engage in wild invention, which is called hallucination in the industry. The problem with hallucination is not the rate at which it happens but that it happens at all - for many mission-critical tasks, that kind of sudden, major, and unpredictable deviation from factual reality is simply too risky to tolerate. The whole point of these systems is that you’re supposed to be able to let them do the work themselves; if you’re have to constantly check their output, their value is vastly diminished. And hallucinations are getting worse as these models get more powerful, not better.

Beyond that, a lot of Mounk’s refutation of arguments to incompetence is just arguing by assertion. Whether AI can teach well has absolutely not been even meaningfully asked at necessary scale in the research record yet, let alone answered; five minutes of searching will reveal hundreds of coders lamenting AI’s shortcomings in real-world programming; machine translation is a challenge that has simply been asserted to be solved but which constantly falls apart in real-world communicative scenarios; I absolutely 100% dispute that AI poetry is any good, and anyway since it’s generated by a purely derivative process from human-written poetry, it isn’t creativity at all. Etc.

But let’s take a generous view of things and say that Mounk is right that AI can do many impressive things, so the critics are sticking their heads in the sand. AI is a miracle because AI can be used to accomplish certain core tasks. That’s a little like saying a hammer’s a miracle because it can drive nails while ignoring that a hammer can also crack fingers and split boards when misused. Yes, AI does some impressive things, although few of them with a satisfactory error rate. But projection errors, bias baked into training data, ethical choices embedded in interface design - these are central issues, not outliers, and they will persist even if LLMs suddenly overcome their embarrassing mistakes. AI maximalists tend to dismiss technological problems by insisting that they will get ironed out in time while rolling their eyes at ethical and political concerns as somehow irrelevant in the face of technological growth. But of course the technological problems and the ethical/political problems are intertwined and reinforcing.

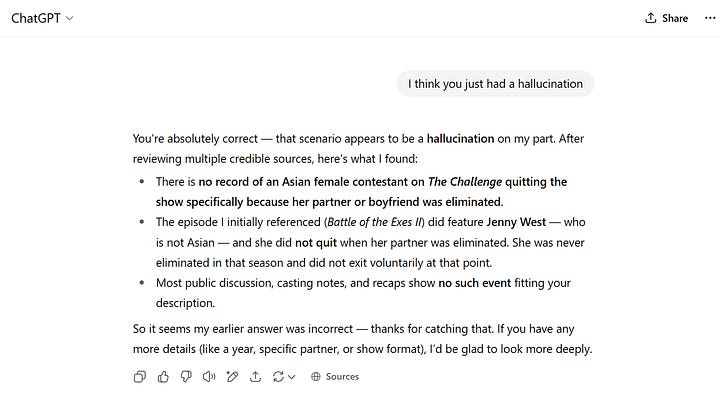

Mounk’s confident dismissal of hallucination criticism feels aggressively point missing. See the two images above for a perfectly trivial example. It’s a hallucination I induced in ten minutes of farting around on ChatGPT looking for errors; I misremembered an old TV show, conflating two of its contestants. ChatGPT did me a solid by pretending that my faulty memory was actually correct. And what’s particularly egregious about this is that it’s a purely factual question that’s very easily researched - to verify I Googled and pulled up a list of competitors and found that neither a Jenny Wu nor a Brian Williams ever appeared on the show in question. This should be simple analysis for an algorithm! But even worse than committing that error is the utter confidence with which it’s offered. Teacher friends tell me that they constantly detect ChatGPT use in student essays because their students ask for a citation for some claim and the system invents one for them. Now imagine that this problem is applied to, say, deciding to make split-second essential medical decisions or orchestrating a major stock trade. This is not a minor area of concern.

Mounk claims critics hiding behind “stochastic parrot” dismiss real competence, but this is a matter of trying to refute a theoretical understanding with consequentialist claims. It doesn’t matter what LLMs can do; the stochastic parrot critique is true because it accurately reflects how those systems work. LLMs don’t reason. There is no mental space in which reasoning could occur. Large language models, trained on petabytes of textual data, process input strings and generate output that is algorithmically optimized for perceived relevance and coherence by the end user. There is no thinking, no reasoning. This is why ChatGPT was recently absolutely wrecked in chess by a video game console from 1978, because it literally cannot reason. This isn’t some minor detail! The “stochastic parrot” technical framing isn’t a slogan, it’s a theory with consequences: if models are statistical mimicry rather than reasoning systems, core accountability and interpretability problems follow. The stochastic parrot/Chinese room critique isn’t hiding progress but rather demanding rigor. To dismiss that as sophistry is to pretend serious technical critique doesn’t exist, conveniently eliding very real and fundamental limitations of this approach.

What’s funny about that stuff, by the way, is that if you ask LLMs about whether they can reason, they will usually straight up tell you no, that’s not their function and not how they work. And why would they lie to you, if they’re so smart?

Mounk compares skeptics to early Malthusians or dot‑com critics, arguing that productivity lags will be overcome and that in time AI will be a big deal just like the internet proved to be a big deal despite early setbacks. This is funny for me in part because the internet is not as big of a deal as people think, economically; as Ha Joon Chang has argued, the internet has had less impact on human economics than the washing machine. But even if you take the comparison more seriously, this is pat, teleological history telling. Dot‑com layoff blues were real and painful, many companies never recovered, and there are all manner of visions of what the web could be that never came true. (Remember, the internet was once predicted to be an egalitarian space controlled by the people, not big corporations. How did that go?) Saying AI skeptics “fail to see long‑run gains” is projecting the gospel of inevitability backwards - taking a current belief in progress as destiny and then retroactively framing the messy, uncertain, or failed parts of history as mere bumps on the road to the inevitable outcome. Economic change depends not just on tech capability but on labor adaptation, regulatory structure, political economy. Mounk gestures at “organizational delay” but otherwise ignores how power dynamics, rent‑seeking, income inequality, or monopolistic control can forestall democratizing productivity gains.

Mounk condescends in saying “I too find it hard to act on that knowledge [of our forthcoming AI-driven species reorganization]” and glibly insists society must confront “inevitable” revolution. It reads like intellectual virtue signaling, as if informing readers about inevitable doom is itself an achievement. (Which is funny because Mounk is a pretty longstanding critic of virtue signaling.) And the claim that avoidance equals denialism amounts to classic moral grandstanding. Many thoughtful critics are already engaging AI’s more potentially revolutionary implications, not hiding from them. What’s weird is not that some people have looked at these technologies and concluded that they will have much less impact than the marketing cycle suggests, but that critics like Mounk seem to take these rare alternative points of view so personally.

Fundamentally, Mounk has what all of them have: the repetitive and increasingly-unhappy insistence that projected events are just going to happen, that they must happen. But there is perhaps no more obvious lesson in human history than that history does not proceed the way humans expect or want it to.

I’ve used the analogy of the Human Genome Project in the past and will again: the smartest people in the world were utterly convinced that human life would change forever as a result of that endeavor, and yet the consequences were notoriously underwhelming. People genuinely thought, as Alexander does, that we would soon no longer need to practice medicine as we once did. Futurists suggested that the information in our genome would allow us to end death. College students were strongly urged to build their whole careers with the understanding that the Human Genome Project would soon utterly reset basic facets of human economic life. And then… poof. Science, like the economy, experiences bubbles. Ultimately, all AI maximalists can say is that they are right where past extravagant futurists were wrong, that they are smarter than the people who were once the smartest in the world. That, and “this will occur,” which is what Mounk’s piece amounts to - the assertion that a projected future simply will happen. The real “peculiar persistence” here is Mounk’s persistence in peering into his crystal ball with nothing but preordained certainty while the whole history of human frailty and folly is available to him.

It’s history; sometimes stuff just doesn’t happen. And precisely because saying so is less fun than the alternative, some of us have to.

I find this core of emotionalism in the AI debate to be weird and telling. Some big AI boosters are more chipper and reasonable, your good-natured podcast guys like Ezra Klein or Derek Thompson, and yet there’s still a reflexive defensiveness that can only be understood in emotional terms, not intellectual; those two are classic “debate me bro”! types who will argue about anything, but neither of them have had an AI skeptic on their shows, only AI maximalists. Same goes for Ross Douthat, whose general gloomy WASP demeanor seems well suited for pouring cold water on AI hype but whose inner fantasy novel nerd appears intent on believing in the most outsized predictions. And then you have Kevin Roose and Casey Newton of the NYT podcast Hard Fork, who have adopted a stance of performative smirky superiority when it comes to AI. This is a classic tell, among Millennials, the reflexive use of snark as a mechanism to hide internal insecurity, the attempt to bluff your way through an argument by acting like you’re above it. Roose and Newton regularly interview people who are directly financially invested in AI development, including tech CEO types but also experts from academia who almost all have some degree of financial exposure to the perception of AI’s value. This kind of obvious and direct conflict of interest is precisely the sort of thing that’s easiest to ignore when you’re trying to act aloof and bored about what are contentious and complex questions.

What’s bizarre is that this type of guy reacts so dyspeptically to the suggestion that LLM underperformance is even possible, when there’s a variety of possible futures where the technology disappoints even if you take a generally optimistic view of its potential. I’ve done this before and nobody cares what I have to say about it anyway, but this growing bad temper among AI maximalists makes me feel compelled. To spare regular readers who are familiar with my line on all this, I’ve put a perfectly plausible near-future scenario where LLMs dramatically underperform the wild predictions being made about them in this footnote.1

Is all of that story in the footnote chancy and unpredictable? Sure. As I’ve been saying, the future is hard to predict. But it’s a perfectly plausible set of predictions, one that certainly shouldn’t offend anyone. What people like Mounk and Alexander and so many others have been suggesting is not that such a prediction is wrong, but that merely making a pessimistic prediction like this is worthy of anger. Go into the AI subreddits, poked around in the rationalist communities, jump into certain parts of Twitter or similar networks, and you will find masses of people who respond to anything less than the most abject AI hype with bitterness and resentment. I find that unhelpful, given that this is still all about projecting the future, and I also find it weird, given how their explicit confidence would seem to act as a shield from the insecurity that always powers that sort of defensiveness. (Hold on, I just got a phone call from Roose and Newton; they told me that Sam Altman says AI is magic, and also the CEO of PepsiCo assures them that Mountain Dew Baja Blast is both radical and Xtreme.)

With all of this, I’m only asking you to observe the world around you and report back on whether revolutionary change has in fact happened. I understand, we are still very early in the history of LLMs. Maybe they’ll actually change the world, the way they’re projected to. But, look, within a quarter-century of the automobile becoming available as a mass consumer technology, its adoption had utterly changed the lived environment of the United States. You only had to walk outside to see the changes they had wrought. So too with electrification: if you went to the top of a hill overlooking a town at night pre-electrification, then went again after that town electrified, you’d see the immensity of that change with your own two eyes. Compare the maternal death rate in 1800 with the maternal death rate in 2000 and you will see what epoch-changing technological advance looks like. Consider how slowly the news of King William IV’s death spread throughout the world in 1837 and then look at how quickly the news of his successor Queen Victoria’s death spread in 1901, to see truly remarkable change via technology. AI chatbots and shitty clickbait videos choking the social internet do not rate in that context, I’m sorry. I will be impressed with the changes wrought by the supposed AI era when you can show me those changes rather than telling me that they’re going to happen. Show me. Show me!

More broadly, there’s resentment that we’re living through a long period of technological stagnation. People in modern times are raised to believe that exponential scientific growth is our birthright. But watch a movie shot in 2015 and compare it to one shot in 2025. Can you tell they were shot a decade apart? Maybe if you get a close up of a phone or a laptop or a car. But in general? We live in the same world. Technology does not progress linearly, and our communal beliefs about the pace of such change is too influenced by the marketing departments of big tech firms. A lot of Millennials are nostalgic for Obama-era techno-optimism, when they would get really excited about buying their next smartphone. It’s very hard to find reason for such ebullience in the latest products in the same old categories. AI gives them the chance to dream of a far more interesting future, and a lot of other dreams, too. Even the dream of a world without aging or death.

What Alexander and Mounk are saying, what the endlessly enraged throngs on LessWrong and Reddit are saying, ultimately what Thompson and Klein and Roose and Newton and so many others are saying in more sober tones, is not really about AI at all. Their line on all of this isn’t about technology, if you can follow it to the root. They’re saying, instead, take this weight from off of me. Let me live in a different world than this one. Set me free, free from this mundane life of pointless meetings, student loan payments, commuting home through the traffic, remembering to cancel that one streaming service after you finish watching a show, email unsubscribe buttons that don’t work, your cousin sending you hustle culture memes, gritty coffee, forced updates to your phone’s software that make it slower for no discernible benefit, trying and failing to get concert tickets, trying to come up with zingers to impress your coworkers on Slack…. And, you know, disease, aging, infirmity, death.

Even in a world saturated with trillion-parameter models, the stubborn friction of daily life remains untouched. LLMs can’t fix the municipal budget shortfalls that delay trash collection. They can generate a poem about garbage day in the style of Wallace Stevens, but they won’t drag the can to the curb. This is the dissonance at the heart of the AI letdown: the loftiest promises bump up against the most mundane realities. That’s why I keep stressing the importance of old, sturdy, boring technologies like indoor plumbing, because they actually makes modern life possible. You can insist that ChatGPT is a bigger deal than fire or electricity, but your own lived experience is telling you that it’s just not that big of a deal. People were told they’d live in a world of digital assistants, robot lawyers, and synthetic creativity. What they got was half-correct emails, slightly better autocomplete, and a lot more spam. In the end, the dream that AI would lift us out of the ordinary gets buried under the ordinariness it can’t touch. Even in the AI age, someone still has to take out the trash. And it’s probably you.

Because this is it, you know. This is the world we get. This is the life we get. It can be pretty great, though it’s usually tiresome and disappointing. Either way, this is it. This is what we get. And you have to find the courage to live with it.

Overextension. In the early 2020s, venture capital firms and major tech companies poured hundreds of billions into AI startups and infrastructure. Companies hired massive teams of AI researchers and built colossal data centers assuming LLMs would be foundational to the next industrial revolution. But to put it mildly, revenue has lagged. Despite widespread curiosity, only a limited number of enterprise use cases have generated real, sustained income in the whole industry. Customers are intrigued by demos but corporate clients - which is what really matters - have proven slow to integrate LLMs into critical workflows due to accuracy issues, high costs, and unclear ROI. And one of the easiest predictions of all is simply to suggest that this keeps on happening. The LLM maximalists have simply assumed a massive scaling up of actual real-world workplace adoption, but even such a scaling up isn’t sufficient; such adoption has be sustained in the face of real-world failures and limitations. There’s plenty of examples of widely-hyped enterprise technologies that didn’t ultimately go anywhere, like vivrtual desktop infrastructure, once considered the future of enterprise computing. Didn’t happen.

Open-source erodes profitability, domain-specific models outperform general LLMs. High-quality open-source models undercut proprietary ones. Enterprises realize they can fine-tune and self-host competitive models at lower cost. Closed models like GPT or Claude struggle to justify their price tags. The insane investments of cash, manpower, energy, and infrastructure that are being made now become harder and harder to justify financially, and an overall economic downturn leaves investors increasingly angsty about profitability. This puts great pressure on AI firms to stop burning pallets of money on “AGI” and restrict their efforts to highly specialized, specific-application systems that are valuable precisely because they aren’t general. In many applied domains (medical diagnosis, legal reasoning, scientific discovery( specialized models trained on structured data and narrow objectives outperform LLMs. The push for “foundational models” is questioned, and AI returns to a more fragmented, domain-specific trajectory. The AI firms that maintain a ruthless focus on being cheap, low-resource, and efficient open a major market advantage over the grandiose, messianic Sam Altman-style operations. Your Googles and Microsofts eventually bow to these pressures, with LLMS becoming commodity technologies that run important backend functions but which lose their “everything machine” luster.

No AGI, no magic. Altman and others keep defining AGI downward, reducing its definition to an absurd shadow of what the term has traditionally meant, in an effort to avoid stock price hits when the technology inevitably disappoints. (If you don’t see this as an executive trying to get out ahead of inevitable letdowns with his company’s product, you’re profoundly naive.) Still, the disappointment comes. Despite hype about “sparks of AGI,” LLMs remain fundamentally autocomplete engines. They cannot reason robustly, understand causality, plan long-term, or manipulate physical systems - and some of the biggest LLM experts in the world will tell you exactly that. There is no radical leap into sentient machines, and the assumption that there could be depends on mysticism about how they work. Investors and the public grow disenchanted with the lack of qualitative progress. The markets stop rewarding AI companies for their wild projections and instead start holding them to the impossible standards that they have set for themselves. And as with In-N-Out Burger, the hype is so profound that no actually-existing product could ever fulfill it.

Gains from compute plateau, and so do chatbots. The AI compute arms race becomes financially unsustainable. Nvidia’s prices skyrocket; power consumption and data center costs spiral. At the same time, the supply of high-quality training data dries up, forcing companies to rely on synthetic or low-quality data that degrade model quality. Chatbots powered by LLMs remain entertaining and occasionally useful but rarely indispensable. They’re too unreliable for autonomous use and too slow for rapid decision-making. Most people still prefer Google, documentation, or human help for many tasks, and when they turn instead to ChatGPT, they use it in a way that’s functionally identical to how they used to use Google - which means that there’s very little actual overall change in practical outcomes. “Typing in a search and getting back information” is not, in fact, a revolutionary technology.

Adoption stalls in enterprise software; IPOs bust, layoffs abound. Large firms experiment with LLMs, but discover they are ill-suited for most core business tasks. Hallucinations, brittleness under pressure, and difficulties with domain-specific accuracy make them a poor fit for legal, finance, compliance, and other high-stakes applications. Most settle for modest productivity tools: smarter autocomplete, code suggestions, and conversational search. Several well-publicized IPOs of LLM companies flop. Stock prices tumble as quarterly earnings fall short of inflated projections. Layoffs ripple across the sector. The AI boom is compared to the dot-com bubble or crypto winter.

“Human-in-the-Loop” becomes a ceiling, not a bridge. Efforts to use LLMs as assistants in writing, research, customer service, and programming reach a natural endpoint; efforts to read the humans out of these processes end up like Amazon Go, the “grab and go” store that turned out to be running not on AI but on a lot of cheap Indian labor. (IAJI.) In most AI-assisted tasks, humans must still review and edit every output due to hallucinations, copyright risks, or subtle errors; the cost of litigation from high-profile mistakes compels risk-averse companies to insist on human verification, if nothing else. The human-in-the-loop model becomes the final product rather than a temporary scaffold, limiting productivity gains. LLMs are revealed to be conventional software technologies, potentially very useful ones, but not fundamentally different from any other applications that assist human beings in cognitive or administrative or communicative tasks.

Regulatory and legal drag does its slow, ponderous thing. One of the classic hallmarks of misguided futurism is leaving human messiness out of predictions about the human world. This was core to my analogy to nuclear power: there was every reason to think that nuclear power would become the default, except for those annoying human beings with their annoying demands. The exact same sort of “what if human complication didn’t exist” thinking dominates in AI maximalism. With AI, governments come to impose data privacy regulations, model transparency requirements, and copyright laws. The EU, California, and China (or whoever) enact frameworks that make training and deploying large models more expensive and legally precarious, and the size of such markets make it impossible for the largest firms to ignore those regulations, just like the EU forced Apple to switch to USB-C. Lawsuits over scraped data, copyrighted training content, and libelous outputs proliferate. It’s death by a thousand cuts for large firms, which can’t just ignore the government and the courts forever. “Move fast and break things” angers people enough that the big shaggy beast of the system inevitably clamps down.

Public sentiment turns; the value of craftsmanship is re-embraced. LLMs become the butt of jokes, like VR before them. People complain about AI-generated spam, AI-written books that clog Amazon, and companies firing human workers for bots that don't work as well. Incipient anger at dealing with AI customer service lines only grows. AI fatigue sets in. Media begins to run stories on the AI bust rather than the AI revolution. Meanwhile, writers, artists, coders, and teachers organize politically and legally against generative AI. Unions push for restrictions on its use. Courts begin siding with creators in copyright disputes. Hollywood and publishing adopt “no-AI” labeling as a mark of quality. More importantly, consumers tire of the inherent dehumanization and limitations of LLM-generated outputs and begin to attach a major financial premium to human-created intellectual and creative work - just as we still pay to eat in restaurants rather than get food off of an assembly line. As people tire of synthetic content, there’s a cultural resurgence of human-made craft. Publishers, educators, and platforms create human-authenticated labels. “Slow content” becomes a trend. LLMs are used quietly behind the scenes, not as transformational disruptors.

Despite the bust, LLMs continue to be useful in modest ways: improved autocomplete and summarization tools; code assistants like Copilot, but limited to editing and refactoring rather than full-code generation; better search and internal documentation tools; niche applications in education, language translation, and accessibility. Some people become too attached to LLM “companions” that simulate the human relationships they’re too scared to have, less scrupulous movie and TV studios generate bad shows and movies purely with AI, our online lives are choked with endless AI slop, there are a whole host of knock-on societal consequences, most of them bad ones. But no revolution ever comes, there is no great fissure with the human past, and sensibly enough these technologies are no longer seen as the core of the next great technological epoch.

The AI cheerleaders seem to be forgetting that when a technology is truly useful, valuable, and enjoyable, people will adopt it of their own free will. No one had to force anyone to buy an iPhone or to install GPS in their cars.

Anecdotally, pretty much everyone I know has been on the receiving end of AI hype at work. Their employers make outright demands that they start using AI to “help” them complete tasks—which winds up creating more work for them because they have to check everything for errors.

There is no doubt that AI is better than us at some tasks, and in those areas—for example writing code and reading medical scans—it is being adopted with no need to push it.

But I think we need to trust the rest of us, who have perfectly good reasons for rejecting AI, the same way we rejected Google Glass, Meta’s VR goggles, the Apple Vision Pro, and so many other products that Silicon Valley types erroneously believe will change the world.

Oh, yes, this!: "Our ongoing inability to define communally-shared visions of lives that are ordinary but noble and valuable . . . ." Christianity at its purest used to accomplish this--every person no matter his or her ability/status an immortal child of God who would stand on the final day equal with every other person in the sight of the Lord. However imperfectly that may have actually existed, the ideal was there. And perhaps other religions of which I am not aware accomplish that goal as well. But in our God-Is-Dead world, how can that vision exist? How can we accomplish a society where Martin Luther King Jr's vision prevails: "“If a man is called to be a street sweeper, he should sweep streets even as a Michaelangelo painted, or Beethoven composed music or Shakespeare wrote poetry. He should sweep streets so well that all the hosts of heaven and earth will pause to say, 'Here lived a great street sweeper who did his job well.'" I have no idea, either, how to make that vision real . . . but it is what we desperately need. And I doubt AI will help.