The audio clip at the beginning of this song - a gem1 from the last gasp of Madonna’s relevance as a pop star - comes from the film adaptation of The Cement Garden. I have not watched it. I suppose this is one of those books where I don’t want the actors from the movie invading my headspace.

This dialogue stems from a bit of gender trouble in the household. Tired of the work of being a boy, Tom resolves to start dressing up as a girl and live as one. There are many trite political readings we could make of this scene; certainly today we would be forced to immediately consider the possibility that Tom is trans, or some such. One of the tricky elements of navigating a world in which we are all expected to be the sum of our various demographic identity categories is that people are forever pressing us into them in a clumsy way. But I think Tom’s little bit of gender anxiety is just an expression of the way kids think; I have no idea what an adult Tom’s gender identity may prove to be, but here he is like so many other little boys in imagining an easier life as a girl. This particular thread is quickly discarded, and it has always struck me as an excuse to motivate the quoted bit of dialogue from Julie. On the one hand, it’s a little clumsy; I don’t think I feel that this particular kind of expression has been set up in Julie in the prior pages of the book, given how reserved and distant she is. On the other hand, it is a lovely little rumination, not necessarily a novel thought but well-expressed in a convincing portrayal of the jumble of head and heart that might come out of a teenager’s lips.

Despite ultimately enjoying that interlude, I still think this section may contain our first false note from McEwan. I found the part where Jack confronts the kid who’s been bullying Tom, resulting in Tom getting beat up worse, to be pretty clichéd. The older child who threatens a younger child’s antagonist, only for the younger child to get an even worse beating, is pretty well-worn territory. Then again, perhaps it wasn’t in the late 1970s when this book was published. Either way I find that this has the same stagey feeling as the gender play that immediately follows it, a sense that I can see McEwan engineering his story in a way that isn’t true for the novel writ large. Safe to say, though, that I notice the strings here in large measure because he does such a subtle and delicate job the rest of the time; these swerves from the book’s overall craftsmanship demonstrate how organic the rest of it feels to me.

In this selection we have Julie manipulating Jack with what seems to pretty clearly be provocative behavior. Having your brother rub suntan lotion on you is not anything inherently nefarious, but doing so as a way to forestall an argument seems rather manipulative. This is especially true given that it would be impossible for Julie to miss Jack’s infatuation with her. I am not accusing her of deliberately and consciously stoking sexual arousal in Jack to further her own selfish ends. But I do think Julie has an unconscious sense of her ability to influence the men around her with physical desire, and like all of the children she’s lacking a sense of appropriate sibling boundaries and has no parental authority present to correct her. There are many valid readings of this book, but I am once again struck by its resistance to easy narratives about culpability and blame. Inappropriate and unhealthy things bloom out of this house, with no one responsible. Trouble grows like weeds.

Speaking of which - it’s in Chapters Three and Four that we are forced to consider the question of the mother’s culpability in what comes next. I said in the first post that this book has trauma without evil and sin without a villain. Some would suggest, I think, that the person who bears the most moral blame is the mother. The father, felled by a sudden (if not unexpected) heart attack, would not appear to be fairly blamed for failing to secure a future for his children. The mother, on the other hand, knew she was now a single mother and knew she had an underlying medical condition. That would seem to suggest that she had a responsibility to set up some sort of plan for her four children in the event of her death, particularly considering that we are told that all the grandparents are dead and there are no aunts and uncles. One friend said to me while reading the book years ago, “how could she not have known she was dying?”

Well, you know… these things are complicated. Denial is a powerful thing. I think it’s entirely possible to simultaneously understand that you’re very ill but also not to really grapple with the reality that you’re dying. And while her children’s reliance on this makes it more tragic, in an odd way I also think it makes it more understandable - she doesn’t think through the possibility of her death because the outcome of that death, her children being totally abandoned, would be unthinkable. In any event, before dying she confides in Jack that she will have to go to the hospital for awhile. It’s unclear to me what she really thinks might happen there; she speaks in vague terms about going away for a long while. I suppose all of this remains sort of distant and unformed in her head. It’s also worth saying that, when you’re orphaned, it’s easy to become everyone’s concern and no one’s responsibility. When my parents died there were outpourings of support from adults who truly meant it, people telling us that we could always reach out to them when we needed to. And I 100% believe that they were telling the truth. The problem is that it’s that first part, the reaching out, that’s the hardest thing in the world when you’re a kid. I can’t tell you how hard it is to be, say, 10 years old and need help from adults who are not your parents. This is the whole deal with parents (whether biological or not): they are the people you don’t have to ask.

One way or another, here we are. Julie, Jack, Sue, and Tom are now orphans, living in a decaying house, all alone, with a dead garden and their mother’s corpse.

Favorite line(s) from this selection: Minute life-bearing spores drifting in clouds across galaxies had been touched by special rays from a dying sun and had hatched into a colossal monster who fed off x-rays and who was now terrorizing regular space traffic between Earth and Mars.

Next week’s reading: Please read Chapters Five and Six by next Wednesday, September 29th.

Questions for the comments: What is the deal with Jack’s sci fi novel, anyway? Is there symbolism there, some meta-commentary? Or is that too obvious for McEwan?

What’s your take on the mother’s culpability?

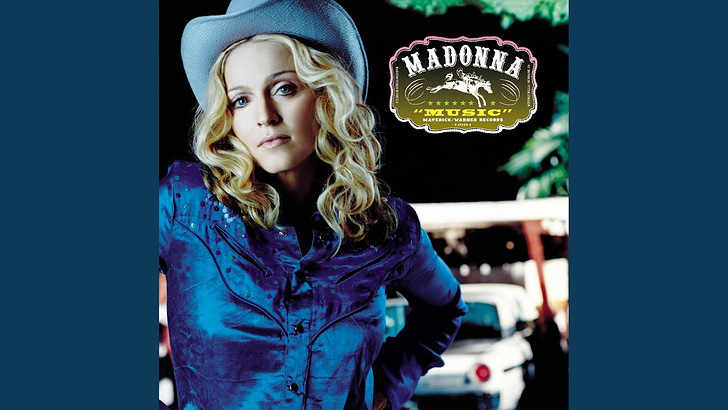

Do you know what it feels like, for a girl?

The dance remix that is attached to the music video is dreadful, however

I was interested in the sledgehammer scene right before the lotion scene. Jack smashing the cement path that was the site of his father's death seems at first like an expression of anger at him. But thinking about it, he was right that there wasn't any use for it anymore. Why not smash it? If you're going to smash something--and smashing things is certainly fun--that seems like the most productive thing to do, rather than smashing something of actual value.

Then Julie says mother wants him to stop, but again he's right (I assume) that she'd been outside and couldn't have heard it from mother. It's an instance of Julie taking control of the family and making her own rules, then asking about the lotion to change the subject. Mother hasn't dies yet, but Julie is already foreseeing it and wants to establish herself as an authority figure. I don't meant to make that sound like she's power hungry, just that she wants to create order.

Felt bad for the kids when reading these chapters. So organized around their parents' excessiveness -- behave yourself at a birthday party or else dad will flip, dance and sing and do cartwheels as mom dies next to the cake. Etc.

On top of that is the unearned nostalgia of the widow -- your father would be so proud, your father would talk to you about becoming a man, etc.

Those kind of background concerns -- essentially "do this weird thing or else mom/dad will do something scary" -- can mutate into manipulativeness. Julie's, e.g. "Mom would want you do that." At this point you're so programmed to do stuff to keep mom and dad at bay, you just kind of roll w/ it, accept it w/o substantiation.

I didn't think of Jack sticking up for his bro, or the feminist broadside as heavy-handed. I sort of liked the latter, in particular, as the kind of performance that otherwise reticent teenager would be happy to engage in, with the bonus points for antagonizing your gross brother. But I did find the sledgehammer maybe a little over the top. Let me go violently destroy the place where I live.