Scott Alexander has responded to my advice that we should not imagine ourselves to be living in some sort of revolutionary epoch. You can decide for yourself if he’s convincing. I continue to maintain the basic point that a) we are definitionally more likely to live in ordinary times than extraordinary and b) we are conditioned to overstate our own uniqueness and importance, not even as a matter of intellect or character but as a basic reality of cognitive science, a consequence of living as a consciousness. I would say that, for one thing, his schema would suggest that someone living in the 1810s or 1860s or 1910s had just as much cause to think that they lived in extraordinary times as we do, and yet Alexander certainly seems to think that now is more important than then. I do want to address this one point.

Freddie sort of starts thinking in this direction6, but shuts it down on the grounds that some people think technological growth rates have slowed down since the mid-20th century. Usually the metric that gets brought out to support this is changes in total factor productivity, which do show the mid-20th century as a more dynamic period than today. So fine, let’s do the same calculation with total productivity. My impression from eyeballing this paper is that about 35% of all increase in TFP growth and 15% of all log TFP growth has still happened during Freddie’s lifetime.

Let’s take as given the claim in the last sentence is true: it’s still inarguable that meaningful technological growth has dramatically slowed in the last 50 years compared to the 100 prior years, to choose an arbitrary but useful comparison. And if that’s true, it suggests that the notion of continuous exponential human growth is nonsense. And if that’s true, it doesn’t in and of itself disprove the narrative that ChatGPT is the Mahdi and will usher us into paradise, but it does make the overarching narrative of a simple exponential climb into a godlike metahuman future harder to maintain. If human development has already slowed significantly, shouldn’t that suggest that it may very well slow further?

I will again refer people to Robert J. Gordon’s The Rise & Fall of American Growth, which is where the 1870-1970 and then 1970-current split is best articulated. I read it, and it’s a classic academic book that ponderously pours data on to the same basic observations over and over again. (Just like, for example, Capital in the Twenty-First Century and many many others.) That’s what an academic book of that type is meant to do; It’s just that I don’t expect anyone else to feel moved to read it. What makes it so valuable, though, is that Gordon spends so much time looking at very specific economic segments and not just demonstrating that productivity and growth have slowed but why they’ve slowed in very specific terms. And I can’t point to a single piece of evidence that does a better job than that book. I would, however, suggest that some common sense would be useful here. I’ll spare you from doing my “time traveler from 1910 traveling to 1960 vs a time traveler from 1960 traveling to 2010” bit in the main text, but you can read it in a footnote below.1 The fundamental observation is simply that beyond the various productivity and growth numbers, the lived experience of being human changed dramatically more from 1870ish through 1970ish than in the 50ish years since then. To repeat myself, a vast majority of what we call the advances of modernity stem directly from the development of cheap, stable, relatively safe, reliable refined fossil fuels, from electricity generation to cars to planes to modern heating systems to fertilizers.

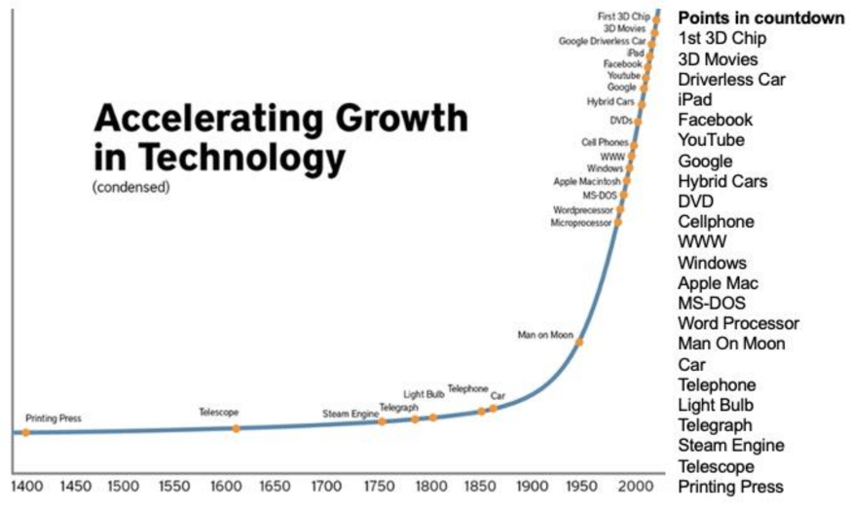

What I’m suggesting is that people trying to insist that we are on the verge of a species-altering change in living conditions and possibilities, and who point to this kind of chart to do so, are letting the scale of these charts obscure the fact that the transition from the original iPhone to the iPhone 14 (fifteen years apart) is not anything like the transition from Sputnik to Apollo 17 (fifteen years apart), that they just aren’t remotely comparable in human terms. The internet is absolutely choked with these dumb charts, which would make you think that the technological leap from the Apple McIntosh to the hybrid car was dramatically more meaningful than the development from the telescope to the telephone. Which is fucking nutty! If you think this chart is particularly bad, go pick another one. They’re all obviously produced with the intent of convincing you that human progress is going to continue to scale exponentially into the future forever. But a) it would frankly be bizarre if that were true, given how actual history actually works and b) we’ve already seen that progress stall out, if we’re only honest with ourselves about what’s been happening. It may be that people are correct to identify contemporary machine learning as the key technology to take us to Valhalla. But I think the notion of continuous exponential growth becomes a lot less credible if you recognize that we haven’t even maintained that growth in the previous half-century.

And the way we talk here matters a great deal. I always get people accusing me of minimizing recent development. But of course I understand how important recent developments have been, particularly in medicine. If you have a young child with cystic fibrosis, their projected lifespan has changed dramatically just in the past year or two. But at a population level, recent improvements to average life expectancy just can’t hold a candle to the era that saw the development of modern germ theory and the first antibiotics and modern anesthesia and the first “dead virus” vaccines and the widespread adoption of medical hygiene rules and oral contraception and exogenous insulin and heart stents, all of which emerged in a 100 year period. This is the issue with insisting on casting every new development in world-historic terms: the brick-and-mortar chip-chip-chip of better living conditions and slow progress gets devalued.

I listened to the latest episode of Derek Thompson’s (highly recommended) Plain English podcast, with DeepMind researcher Pushmeet Kohli. Kohli and his colleagues are using machine learning in drug discovery, particularly through the protein folding that’s such an essential element of developing new medicines. This work, they demonstrate, is well-suited to what modern large language models can do. It’s also one of the very, very few places where the hype for these systems might actually be warranted; the vast majority of breathlessly-discussed “AI” possibilities would not even be particularly transformative if they came to pass, which most of them won’t. (AI doomerism relies on the idea that consciousness, superintelligence, and ill intent will prove to be “emergent” properties of LLMs, which no one can articulate in remotely rigorous terms and which most actual LLM researchers dismiss as nonsense.) Drug discovery is definitely a big deal and these tools seem very promising. The question Derek didn’t ask is, I think, a central one: why call this “artificial intelligence” at all? Nothing that DeepMind is working on requires “emergence.” Their tools are not agentic/choice-making. They have no consciousness, nor are they required to in order to fulfill their purpose. They’re very powerful systems built on very powerful algorithms but that’s fundamentally what they are, systems built on algorithms. So where does intelligence come in at all, and why is it necessary?

This is part of the basic poverty of the current “AI” discourse - the core concept of agentic, self-directed, learning, and conscious computer technology has given way to just any instance of “a computer doing complicated stuff.” DeepMind is developing a potentially profoundly-useful technology built on algorithms that appear to work. Why is that not enough? Algorithms that work are good enough.

In the podcast, Derek says that GPT has mapped human language. I would push back against that, forcefully - a map is not probabilistic. You can have a better or a worse map, but a map is not fundamentally stochastic and GPT’s understanding of language will always have error bars, due to its basic architecture. This is why “AI” has conspicuously failed in one of the many tasks it is confidently asserted to be on the brink of solving, which is producing a complete and functioning syntax for the grammar of a human language. This was exactly Chomsky’s point when he and colleagues critiqued ChatGPT; the modern era of linguistics began precisely when he and his generation came to understand that language is rule-bound in a way that is fundamentally neurological and probably genetic. (Which is to say, it does not rely on the ingestion of data, hence the poverty of the stimulus.) And that’s precisely what LLMs don’t do, proceed from a list of static rules and build understanding step-wise. If they did, tech companies wouldn’t be where they are now, which is trying to somehow ingest more language data than has ever been produced by all human beings combined in the history of the world.

What unites the two preceding paragraphs is simply this: my confusion as to why reality itself is never good enough. Why does our culture insist on overselling and overhyping when there are genuinely impressive developments happening? Is it just literally about stock prices? I think it might literally be about stock prices.

Here’s some things I think, without any particular qualifications to think them.

The speed of light is an actual hard speed limit; various sci-fi tricks like warp drive and traveling through wormholes have immense practical and theoretical barriers to being usable and I don’t think they’ll ever be overcome

Time travel into the past actually is impossible, which is why no one has ever come back to tell us about it

Even if we achieve speeds on the order of (say) 10% of the speed of light, which we almost certainly can’t for simple relativity reasons, traveling to potentially habitable stars will take hundreds of years; we have no reason to believe that cryofreeze/stasis/etc technologies are actually achievable; multigenerational interstellar travel is likely impossible for all the reasons Kim Stanley Robinson lays out here; we will therefore never colonize the stars and in the exceedingly unlikely event that we survive to see it, we’ll die when our sun expands to become a red giant; we might mine or colonize planets or moons in our solar system, but that won’t fundamentally change human life

There’s very likely other life in the universe, even intelligent life, but given that the cosmic speed limit will apply to them too, we’ll never meet with any of them physically, and given the distances involved synchronous communication is essentially impossible

Quantum entanglement won’t allow for faster-than-light communication for the reasons enumerated in this video

We don’t live in a simulation

Even if there are many worlds/multiple dimensions we’ll never experience them directly and thus they’ll have no practical impact on our lives

We’ll never “upload” our consciousness into computers to live forever, which suggests that there is some such thing as our consciousness separate from the physiological structures that contain it, which is a dualist fantasy

Artificial intelligences of various kinds will develop and emerge and have meaningful consequences for humans and improve quality of life, but they won’t somehow enable us to transcend the physical limitations of the material world, that is, no free energy, no breaking the laws of physics, no eternal life

We’re all going to die, and it’s going to feel far too soon for almost all of us.

Look, stuff is gonna happen. Technology is going to grow. A lot of it will be good and some of it will be bad. I don’t doubt, for example, that in a hundred years the science of human genomic editing will fundamentally transform many elements of human life and, in particular, undermine basic human notions of “meritocracy” and just deserts. Obviously, that could go do a lot of bad as well as a lot of good. I could also easily see a world, even in a decade or two, where a significant chunk of the human population spends almost all of its time in virtual reality and essentially disconnects from actual human life; that sounds straightforwardly bad, to me, and would justify anti-tech terrorism. One way or another life is gonna change. Human beings will change. Life expectancy is going to increase. We’re gonna have a lot of cool new toys. But, fundamentally, we live in a mundane universe and that will never change.

And, crucially, it’s our nature to adapt to make the extraordinary seem mundane. I’m a big believer in a steady state/thermostatic concept of happiness, which suggests that we mostly have our own individual levels of default life satisfaction and we tend to gravitate to that level over time. It’s not that events just don’t matter for how we feel; if you fall in love you’ll feel more happy and if you go to prison you’ll feel more unhappy. Of course you can make your life better and be an incrementally happier person. I have, over the course of my own life. But we reliably, slowly adapt to change and float back towards our baseline level of life satisfaction. And with technology, particularly, things that seem remarkable come to seem boring at a relentless pace. Smartphone sales have slowed because we’ve wrung all the innovation out of them that we can and people now see them as commodities. Who’s excited to upgrade from a Galaxy Sx to a Galaxy Sx+1, no matter how remarkable the underlying technology? The PlayStation 5 Pro is an absolutely remarkable piece of human ingenuity, and yet many people feel cynical and underwhelmed about it, and I don’t blame them. The Nintendo64, now, that felt revolutionary. Is that fair, the ever-ratcheting expectations game? Doesn’t matter. It’s human nature.

Ultimately, I do want to tell people to please try and chill out, yes. No, I don’t think AI Jesus is about to come and initiate the Rapture, and the desire for that to be true seems to be derived from very naked psychological needs. We live in a mundane world, a world of homework and waiting for the bus and sorting the recyclables and doing the laundry and holding your shirt over your nose when you enter a public bathroom and trying to find a credit card that offers a slightly better points program. It just keeps going, day after day after grinding day. You never get removed from it, never escape it. And yes, there’s transcendence and beauty and fun and satisfaction and growth and meaning, all of it! But you find that all in the mundane, generally; those few who spend their lives in a state of constant stimulation and novelty, well, God bless them. Most of the time they didn’t get there through their choices but through random chance. I’m saying all of this because I think a lot of people spend their time yearning for some great fissure in their lives where there’s a massive and permanent division between the before and the after, and all of this AI stuff is giving rational people an excuse to be irrational. (Of course, this is the number two fantasy behind the great American civic religion, “Someday, I’ll be a celebrity.”)

You have to imagine a life you can live with, where you are, when you are. If you don’t, you’ll never be satisfied. Neither AI nor anything else is coming to save you from the things you don’t like about being a person. The better life you absolutely can build isn’t going to be brought to you by ChatGPT but by your own steady uphill clawing and through careful management of your own expectations. You live here. This is it. That’s what I would tell to everyone out there: this is it. This is it. This is it. You’re never going to hang out with Mr. Data on the Holodeck. I know that, for a lot of people, mundane reality is everything they want to escape. But it could be so much worse.

A person living in the United States the 1910s would be someone who

Very likely did not have indoor plumbing, meaning they used an outhouse, got water from a well, could not routinely bathe or wash their hands, and was subject to all manner of illness for these reasons, to say nothing of the unpleasant nature of lacking these amenities

Almost certainly did not have an electrified home, the consequences of which are obviously numerous and significant compared to modern existence

Had no artificial refrigeration at all and relied on blocks of delivered ice where possible, which when combined with a lack of modern food production regulation and hygienic storage led to vastly higher rates of foodborne illness

Got around by horse and cart for anything nearby, taking hours to go more than a few miles; got around by train for anything domestic and far away, remarkably fast in many ways but still slow compared to plane travel and on set schedules and from and to a certain set number of places; got around by steamship if having to travel over water, which was very expensive for ordinary people and glacially slow compared to modern methods

Could expect to see their children die at a rate of about 15% in the first year of life and could expect to die themselves (as the mother) or their partner to die (as the father) at a rate of about 1%

Had a life expectancy of about 45 to 50 years if a man and about 50 to 55 years if a woman, and faced the looming threat of the 1918 influenza pandemic (which killed something like 700,000 Americans) to say nothing of the constant threats of polio (27,000 cases in the 1916 outbreak alone), tuberculosis (200,000 new American cases a year and 100,000-150,000 deaths a year in the 1910s), and all manner of infectious diseases that are now eminently treatable

Did not yet have commercial radio, though ham radio technology existed (for those with access to electricity); nor was there television, obviously; only 10% of households had a telephone; telegraph technology existed and was remarkably sophisticated but not very accessible

I could go on. Let’s say we teleport our 1910 fellow to 1960.

Outside of a few stubborn places in the deep South and some truly out-of-the-way rural locales, almost all American homes have indoor plumbing, which allows for using a flush toilet, washing your hands, regularly taking showers or baths, and having handy access to clean water for drinking and cooking

The vast majority of American homes are electrified, allowing for indoor artificial lighting without the fumes or dangers of oil-based light, along with a myriad of household gadgets and devices

Most American homes have refrigerators, expanding the kinds of foods that are practical accessible (with help from modern supply lines and transportation) and seriously reducing the risks of food poisoning and similar ills

80+% of American households have a car, dramatically expanding the geographical range that can be traveled, reducing transportation time in all manner of contexts, and making long commutes for work practically possible, albeit with major consequences for safety and the environment

The infant mortality rate in the first year of life has plunged to 2.6%, while the maternal mortality rate has fallen to less than .05%.

Men’s life expectancy has grown to more than 65 years and women’s to about 73 years; the incidence of new cases of polio had fallen to about 3,000 by 1960 and in the next several years the disease would be essentially eradicated from the United States; there were some 84,000 new cases of tuberculosis, almost all of them in rural and impoverished areas, and the survival rate was meaningfully higher; ordinary Americans now had a decent shot at having access to chemotherapy, antibiotics, heart bypass surgery….

90% of American households have a radio, better than 85% have a television, bringing information and entertainment into the homes of millions; 90% have a telephone, enabling instant peer-to-peer communication with a vast network and dramatically improving the capability of emergency services, practical access to information, the ability to socialize and connect with those who are geogrpahically distance, etc etc….

Again, I could go on. The 1910 person would find the world utterly transformed. The interstate highway system, in and of and by itself, is a change that’s absolutely massive in the most practical and physical and meaningful terms. Every aspect of life has changed in deep, obvious, material ways. Now let’s take someone from 1960 to 2010.

It is still the case that almost all American households have indoor plumbing; the number without has fallen, but because of ceiling effects the amount of change is vastly smaller than from 1910 to 1960; indoor plumbing has already been accomplished

It is still the case that almost all American households have electricity; the number without has fallen, but because of ceiling effects the amount of change is vastly smaller than from 1910 to 1960; electrification has already been accomplished

Most American homes still have refrigerators; they’re nicer and bigger and more energy efficient but they do the same thing; regulatory standards are maybe, maybe, maybe a little better?; the range of foods available has increased, maybe the quality, but the change is vastly smaller than from 1910 to 1960

The percentage of American households with cars has risen to 90%. That increase is meaningful but doesn’t represent any revolutionary change to average living conditions. The cars are way, way safer and nicer than those in 1960, but they’re still almost exclusively burning fossil fuels and otherwise function in the same way that they did in the 1960s. The interstate system has expanded but someone driving on it in 2010 might not even notice any difference since 1960

The infant mortality rate has fallen from 26 per 1000 in 1960 to 6 per 1000 in 2010. That’s a lot! But it’s very small compared to the improvement from 1910 to 1960. Similarly, the maternal mortality rate has improved but from next to nothing to even closer to nothing

Men’s life expectancy has grown to about 76.2 years for men and 81 for women; again, meaningful and important but simply not at the same scale as from 1910 to 1960

Almost everybody has a telephone, but that was true in 1960; almost everybody has a television, but that was true in 2010. They are much more sophisticated and now portable and can access far more content, but in both cases the changes are a matter of refinement and development, not dramatic innovation. In general, information technology has proceeded at a remarkable pace, but in terms of the actual lived experience of human beings, it’s very difficult to argue that the introduction of the internet etc can keep pace with the immense practical and material changes introduced in the previous era.

Yay, Substack has revived what used to be my favorite part of the New York Review of Books, the letters to the editor column where intellectuals would battle back and forth (e.g. Gould vs Dawkins).

There is also the other side of the argument where people are incredibly uncomfortable with all the magic and wonder that will occur after they are gone. It’s more comforting to think the future will resemble the now than to think of all that will be that one won’t be around to experience.