The YIMBYs and Social Capture

what happens when people who are right on the substance become obsessed with being an online social culture?

The (useful) video above proffers four answers to its titular question.

Tastes changing with the times.

Sheer necessity to house people.

Housing becoming a commodity instead of a place to live.

Car-centric urban planning.

It happens that I am one of those that believe that contemporary buildings are generally speaking less aesthetically pleasing than older buildings, and I think that this is a genuine social problem - the point of human progress is not merely to exist but to create beauty, and in fact an essential value of modernization is that greater efficiency at producing the necessities of life affords us more time, energy, and money to create the beautiful things that make life worth living. In this video, the narrator mainly defines architectural beauty as highly-ornamental premodern buildings, but there’s no reason to think in those terms; there are many ways that a building can be more beautiful (or uglier) without reference to that older architecture. What strikes me, particularly, is that three of these four reasons (the first, third, and fourth) are not intrinsic at all, but social choices, and we could choose something else.

The second is trickier. The idea is that the costs associated with building with aesthetics in mind are costs that could better be spent simply on capacity. In this telling, we stopped building beautiful structures because we thought that the money would be better spent on making the buildings bigger to accommodate more stuff and people. I find this logic dubious. To begin with, while there certainly is far more need for total capacity in the system now given our higher population, it’s not clear to me why, for any given building, the capacity-aesthetics calculus would be any different in the 1930s than it is today. What was inherently different then that would compel architects to prioritize aesthetics over capacity? It’s also a strange assumption because it’s not like every building, or even most buildings, are designed with maximum total capacity in mind. (Why would we build six story buildings when we could build eight or ten or twelve?) What’s more, we’re a vastly, vastly richer nation than we were in the heyday of more ornamented buildings. Why would we have fewer available resources to devote to making things look good than we did a hundred years ago? But most importantly, I find this unconvincing because I don’t believe that building with better aesthetics is necessarily much more expensive. Here the definition of architectural beauty as that which is more ornamented gets in the way; ornamented buildings might be more expensive, but more beautiful buildings don’t have to be. I can think of many low- or no-cost changes to make a building more visually appealing.

You’d think, then, that we could comfortably say that there is no intrinsic reason why there should be a conflict between increasing capacity and caring about aesthetics. And even if aesthetics have non-zero costs, it’s not clear why that would uniquely disqualify them, when any building project involves balancing costs and benefits like features and amenities. (Indeed, I think it would be the worst possible thing for the housing abundance agenda if new mass housing projects became defined in the public imagination as grey, featureless, and utterly without character.) A housing abundance agenda should also be a good housing abundance agenda, and good housing doesn’t look like shit.

Ah, but: the YIMBYs, the Yes in My Back Yard movement, is absolutely filled with people who think that ugliness is a virtue. On YIMBY Reddit, YIMBY Facebook, and YIMBY Twitter, you will very often find YIMBYs celebrating ugly buildings, for their ugliness and as ugly buildings. They’ll show some hideous building, often noting some non-YIMBY’s negative reaction to it, and celebrate it for its very ugliness. There’s a ton of petulant thrills being had based on triggering people by praising ugly buildings. A blogger captured the YIMBY preference for ugliness very well in writing that he “came across something that made me ask, can a developer make a building so ugly even a YIMBY can’t love it? (Roughly analogous to the old test o’ faith can God make a rock so heavy even He can’t lift it?)” Let me be clear: the problem is not that YIMBY types argue for the prioritization of capacity over aesthetics. That would be eminently defensible, although again I’d stress that there is no real conflict between aesthetics and capacity. I’m talking about evincing a preference for ugliness as such. There’s a premium placed not just on defending ugly buildings but on antagonizing normies in doing so. “NIMBYs often prioritize aesthetics in a destructive way, so we’ll actively prefer bad aesthetics” seems to be the reasoning.

And this is social capture. It’s a very common aspect of online life, endemic to social media: as communities form based on shared values or interests, those communities develop markers of in-group identity that have little to do with advancing the substantive agenda of the group. Because mocking people who disagree with you is fun, people who mock ideological enemies are advanced in online social cultures; because slowly and painstakingly advancing the interests of the group is less fun and harder to see, those who do so are less likely to benefit. It’s a constant phenomenon of, for example, subreddits - the social incentives cut in favor of nastiness and extremity and against nuance and bridge-building, so the forums gradually become ugly places that are hostile to dissent and which celebrate excessive expressions of the group’s orthodoxies precisely because they’re excessive. They become victims of social capture; the interests of appearing to be a member of the club in good standing cut directly against interest in outreach and moderation. When these forums are about MCU movies or basketball, the cost is low. When they’re part of an effort to solve pressing social problems through badly-needed policy change, it’s a problem.

I know I constantly invoke Jon Schwartz’s Iron Law of Institutions, but the phenomenon I’m describing is a great example. Schwartz’s law says that people within institutions do what benefits their own position within the institution, not what’s best for the institution. Showily associating YIMBY principles with ugly housing is straightforwardly bad for the YIMBY movement. But doing so can improve your social position within the YIMBY movement, or at least within its online forums. And the incentive structure built into online life deepens this problem. The guy who says “I’m so dedicated to YIMBYism that I’m going to act as though ugly buildings should be preferred, since NIMBYs place too much emphasis on aesthetics” is going to get more upvotes or likes or whatever from fellow travelers, as it’s a more extreme expression of their ideology. The guy who says “you know, actively rejecting the aesthetic values of most normies doesn’t seem like a good political move” is just spoiling the fun.

It happens that Matt Yglesias, maybe the most prominent YIMBY in the media, has recently weighed in on the ugly buildings question.

I’m glad to be informed that there are in fact only two human emotions, respect and disgust. So annoying that we couldn’t have a more nuanced opinion! If that were permitted, I would say that this expansion in supply is great, and it’s a shame that it was built to look like shit. I would also say that it’s a false choice to suggest that we can either have increased capacity or buildings that don’t look like ass. We can have both! But the social incentives push Yglesias to adopt a binary, us-vs-them framing that only allows for two extremes. For it to be a litmus test - for it to separate the in-group from the out-group, which is the real priority - the question has to be posed as all or nothing. And this is precisely the issue.

I believe that we need to expand our housing supply dramatically; I believe that in order to do so we need to significantly reduce the zoning and regulatory burdens that stop us from doing so; I think absurdities like minimum parking requirements should be abolished on the federal level if possible; I believe that we should be allowing for the conversion of commercial space into residential space, right now; I think that any solution to the homelessness crisis must address the lack of housing first, among other essential interventions. In 90% of the questions regarding housing policy, I side with the YIMBY consensus. And I have articulated these values, sometimes at personal cost, in the venues of tenant’s rights activism that I’ve been a part of for over six years, spaces where most YIMBYs wouldn’t step foot. I really believe in this stuff.

And yet despite all of that, I’m not a YIMBY, because the YIMBY movement is unwilling to define what it is. YIMBYs seem unable to decide whether YIMBYism is a pragmatic political movement that’s willing to compromise and work with its enemies when necessary to achieve positive change, or a very online social club that’s defined primarily by its hectoring and dismissive tone and the deeply held view that, because NIMBYism is so obviously wrong, YIMBYs have no obligation to do politics. To go along with the common-sense policy positions and correct perspective on the macro housing situation, YIMBYism involves a lot of people who simply moon around being better than everyone, under the apparent theory that they can simply mock NIMBYs until the universe decides to change itself. No need to speak with respect to those with whom they disagree, no need to build coalitions with left housing activists who are deeply skeptical of neoliberal NIMBYism, no need to slowly and carefully persuade. But that’s exactly what it will take to dismantle the highly localized zoning barriers to more housing.

I’m also frustrated that YIMBYs seem congenitally unable to understand that

NIMBYs are rational actors; their interests are contrary to the public interest and they should lose, but there’s nothing irrational about their actions, and this is profoundly important for understanding the strategic political situation;

NIMBYism is a profoundly cross-racial, cross-class phenomenon, not merely a movement of affluent whites, as would be emotionally convenient;

The affordability benefits of increased housing supply in a given neighborhood are diffuse and take time to accrue, while changes to the neighborhood’s demographics are immediately observable, leading to fears of gentrification that contribute to local resistance to new building;

Leftist distrust towards landlords and developers is profoundly legitimate given the long history of bad actors within those groups;

We can and should argue that the value of neighborhood character is lower than the value of housing people, but it’s both wrong and a strategic mistake to constantly talk as though the value of neighborhood character is literally zero; we know that this isn’t true based on people’s behavior, as many of the most desirable places to live (like Park Slope or Georgetown or Lincoln Park etc.) are so desirable precisely because of neighborhood character.

I’ve found YIMBY spaces to be deeply resistant to these kinds of perspectives in a way that exceeds the rational defense of their beliefs. And I think social capture explains why.

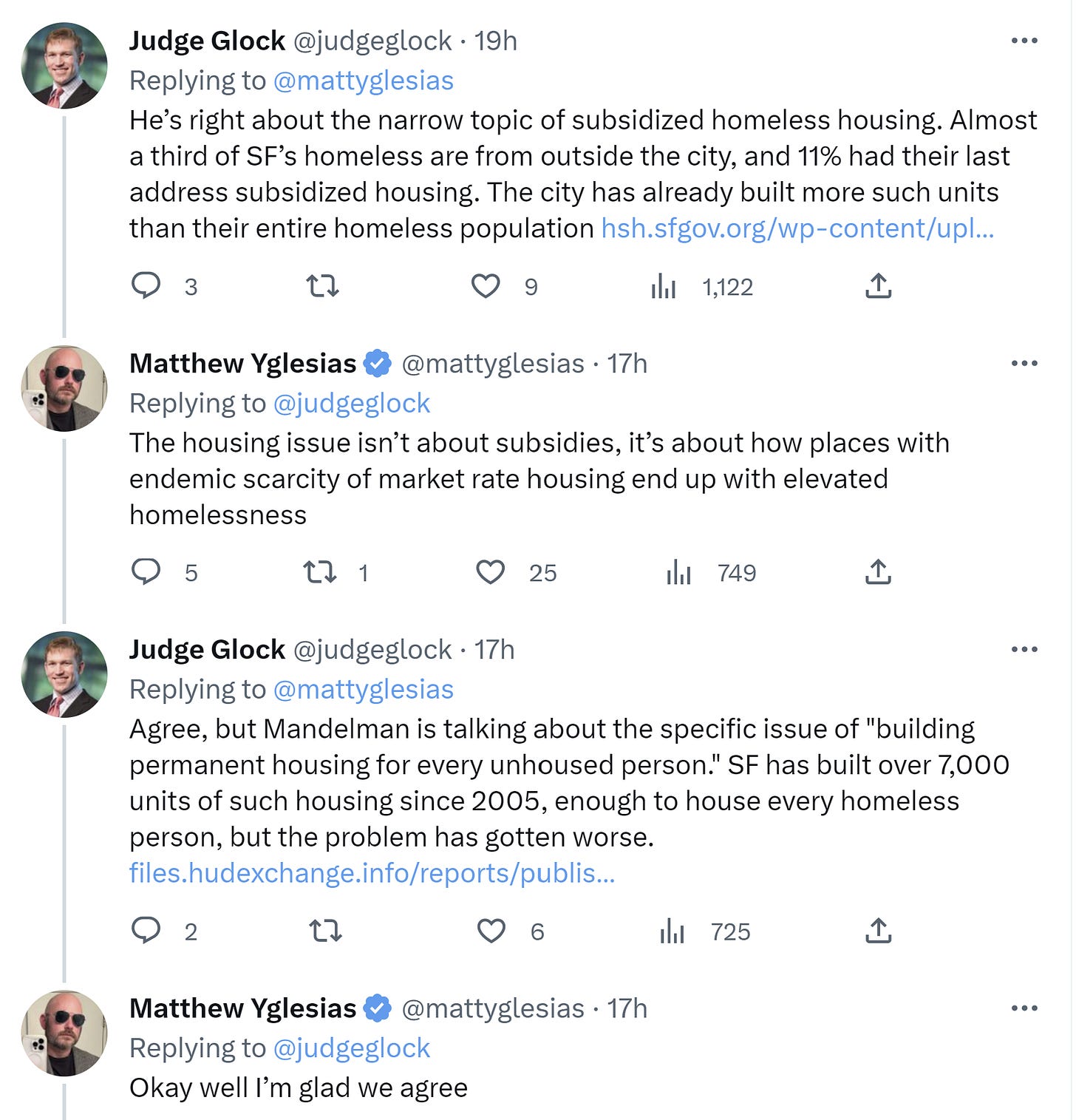

This problem is deeper than simply being repetitively snide. Here’s Yglesias again in an exchange with an interlocutor who’s obviously acting in good faith and makes an important point based on accurate data:

Totally non-responsive on the actual issue of basic substance here. It’s in fact very fair to ask why San Francisco’s efforts to build more units haven’t resulted in more obvious improvement in the homelessness problem. There’s no intrinsic reason why this question should be hostile to YIMBY interests at all. But it is hostile to YIMBY social culture, which insists that there is no valid answer to any housing question but “SUPPLY.” Yglesias is not rejecting a perfectly reasonable inquiry about housing because that inquiry is somehow antagonistic to the goal of building more but because YIMBY social culture is insular and derisive. To admit that it’s not true that every housing issue is totally reducible to pure supply and demand doesn’t threaten the movement for housing abundance. But it does threaten the sneering maximalism that’s so often employed by YIMBYs when discussing these issues.

We need a lot more housing. The YIMBY movement will be an essential part of getting it. But they have to accept that they need to do politics like everyone else. That means not acting as though they can reform our current system by scoffing at how dumb it is. That means breaking bread with people they don’t like. That means attenuating their messaging when appropriate. That means confronting the additional complexities inherent to homelessness. That means not acting like zealots who have talked themselves into a corner where they can only ever diagnose a lack of supply as the only problem. And it means not acting like jerks. I think that this can be achieved. But first people within YIMBYism have to admit there’s a problem.

I'm with you on this. I'm very sympathetic to YIMBYism, but it does become cultish at times. In particular, they tend to waive away costs of their proposals. You touch on this with the "neighborhood character" thing. People legitimately like living in certain types of areas, and having to move every so often to continue to do so is a cost.

There's also this idea, often pushed by Yglesias (of who I am generally a big fan) that upzoning actually increases property values because it let's you use your property for higher value things. Maybe this is true, but its certainly not a priori true. Sure my property value will go up if I all the sudden can all of the sudden redevelop my property in an apartment building, but maybe not if several of my neighbors have already done so by the time I get around to it.

Now it may be that we are in a place where it's worth making people bear these costs (I think we are to a certain extent, which is why I am sympathetic to YIMBYism), but you have to convince people of this. Movements often try to dismiss the other sides objections as meritless, but they almost never are truely meritless. When you do this, all you do is alienate potential converts, because they can see that you are bullshitting them on this one point, and assume you must be bullshitting them on everything else as well.

As an aside, another good example of this was the left's response to the anti-CRT movement. There is a lot of merit to the ideas that racism is continues to be a big problem in this country and that it should be discussed in schools, but the left didn't make this argument, they basically just said "nothing has changed and if you think it has, you're a racist." Since things pretty clearly had changed, and since most of the people concerned about this knew (or at least beleived) they were not racists, this line of argument did nothing but convince a lot of people raising good faith (even if potentially misguided) concern, to think that that the left was lying to them and maybe they should listen to Chris Rufo after all.

I believe Yglesias is using a Twitter meme template here:

https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/a-pretty-good-litmus-test-for-politics

That I knew this immediately and could think of a half dozen other examples in many weird social contexts is causing me to reevaluate how I spend my time.